Charles will not cool on climate action, say friends

- Published

King Charles III as a young man in Snowdonia

Will King Charles III turn his back on a lifetime of environmental campaigning?

As Prince of Wales he spent decades campaigning, cajoling, and convening meetings to drive action on environmental issues.

As king he is subject to different rules - the monarch is obliged to remain politically neutral.

But his friends and advisers say he will not cool on the issue of global warming.

Might urging action on key global issues like climate change or biodiversity loss be part of what a modern monarchy looks like?

King Charles' interests have ranged from tropical forests to the ocean depths, from sustainable farming practices to water security. They began long before such concerns became mainstream.

Within months of his investiture as Prince of Wales in 1969, the 20-year-old Prince Charles wrote to Prime Minister Harold Wilson worried about the decline of salmon stocks in Scottish rivers. "People are notoriously short-sighted when it comes to questions of wildlife," he complained.

Increasingly he has focused on tackling global warming, which he regards as one of the greatest challenges humanity has ever faced. He was a major presence at the COP26 global climate summit in Glasgow last year, urging world leaders to work together to save the planet during a speech at the opening ceremony, external.

When I interviewed him ahead of COP26 he told me "It has taken far too long" for the world to respond to the risks of climate change. I pointed out world leaders would soon be gathering to talk about the climate crisis, he responded: "But they just talk, the problem is to get action."

King Charles III interviewed by BBC Climate Editor Justin Rowlatt last year: "People should really notice how despairing some young people are" about climate change.

He even said he understood why some people felt motivated to take to the streets with organisations like Extinction Rebellion, noting "people should really notice how despairing so many young people are".

As for the risk of not taking action, he was very clear: "It will be a disaster. It will be catastrophic. It is already beginning to be catastrophic because nothing in nature can survive the stress that is created by these extremes of weather."

The veteran green campaigner Tony Juniper rates the new king as "possibly the most significant environmental figure of all time". Chairman of Natural England and a long-term adviser to Charles, Mr Juniper has spoken of the "incredible depth" of his knowledge and the "absolutely enormous" impact he has had.

The question is whether as king, Charles, will be so outspoken on this or any other issue.

"Everything we know about how he has thought about his accession, tells us he will be absolutely clear about his constitutional duties," says Jonathan Porritt, former head of Friends of the Earth and an ex-adviser to the new king.

King Charles has said as much himself. When asked in an interview in 2018 whether he would be a "meddling" king he replied "I am not that stupid" and referred to suggestions he would continue to lobby parliamentarians as "nonsense".

Connector of people

When I asked him last year whether he thought the government of then Prime Minister Boris Johnson was doing enough to tackle the climate issue, he laughed. "I couldn't possibly comment."

And, last week, the new king acknowledged it would "not be possible for me to give as much of my time and energies to the charities and issues for which I care so deeply".

But his passion for environmental issues will not suddenly evaporate. Much of his work had already taken place away from the glare of publicity.

"The King is a convener, connecting people and organisations in ways that open up possibilities and create solutions," says his former press secretary, Julian Payne. Charles would invite "the best brains and the most experienced people and listen to their ideas and advice".

"I suspect it is a modus operandi that will continue as he takes on this new role," says Mr Payne..

Charles's approach to problem-solving has led to some unexpected initiatives. Look how he worked to engage the accountancy profession in tackling climate change, says Mr Porritt.

He recognised the world would need ways of calculating emissions and judging the progress of companies, says Mr Porritt. And, in 2004, he set up the Accounting for Sustainability Project, to attempt to begin to work out how that might be done.

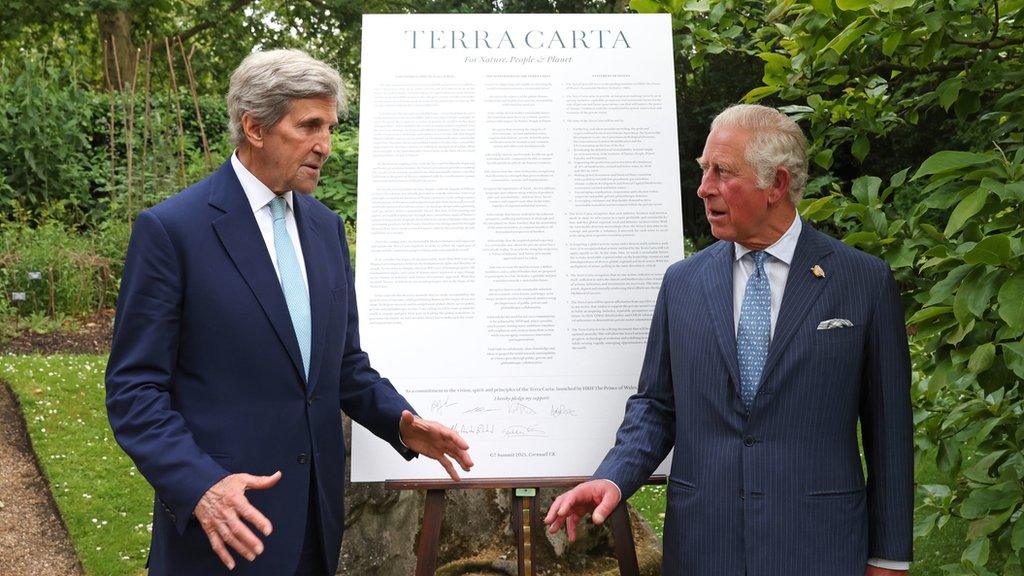

Terra Carta pledges

In recent years he has worked to encourage the business community to help lead action on climate change. More than 500 chief executives - including the heads of some of the biggest financial institutions and businesses in the world - are now part of his Sustainable Markets Initiative, external.

They are described as a as a "coalition of the willing" and have signed up to his "Terra Carta, external" pledges, agreeing to "rapidly accelerate the transition towards a sustainable future".

"We need a vast military-style campaign to marshal the strength of the global private sector," Charles said when he opened COP26.

One senior British politician told me he could imagine Charles making a similar speech as king. "You won't hear him expressing a view on fracking," he said, "but I can imagine him making a speech on the need to take more urgent action on climate."

US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry hopes King Charles will still press for action on climate

US President Joe Biden's climate envoy, John Kerry, agrees. He has said he hopes Charles will continue to press for action on climate.

"It is a universal issue, it is not ideology," Mr Kerry told the BBC Radio 4 Today programme, "It's about the survival of the planet. I can't imagine him not wanting to [press for action on climate] and feeling compelled to use the important role as the monarch and urge the world to do the things the world needs to do."

Tackling climate change is, after all, an obligation on governments that is enshrined in UK law.

The Climate Change Act requires the government reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050.

All the main parties agree it is an important priority. Prime Minister Liz Truss has already said her government will "double down" on reaching the target.

So, here's a question King Charles III will have already considered: how controversial is it for a British monarch to express general support for something that is already enshrined in law.

- Published11 October 2021

- Published9 September 2022