World's oldest heart found in prehistoric fish

- Published

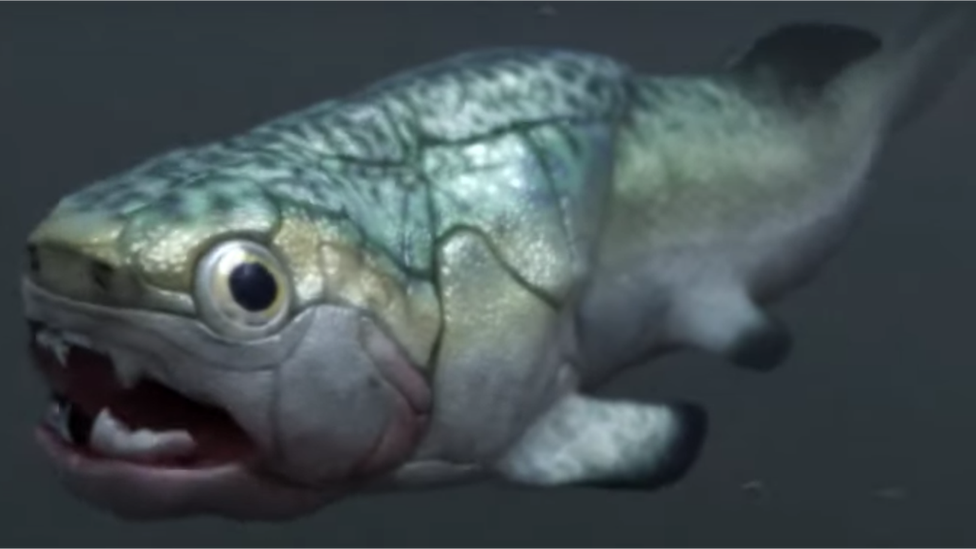

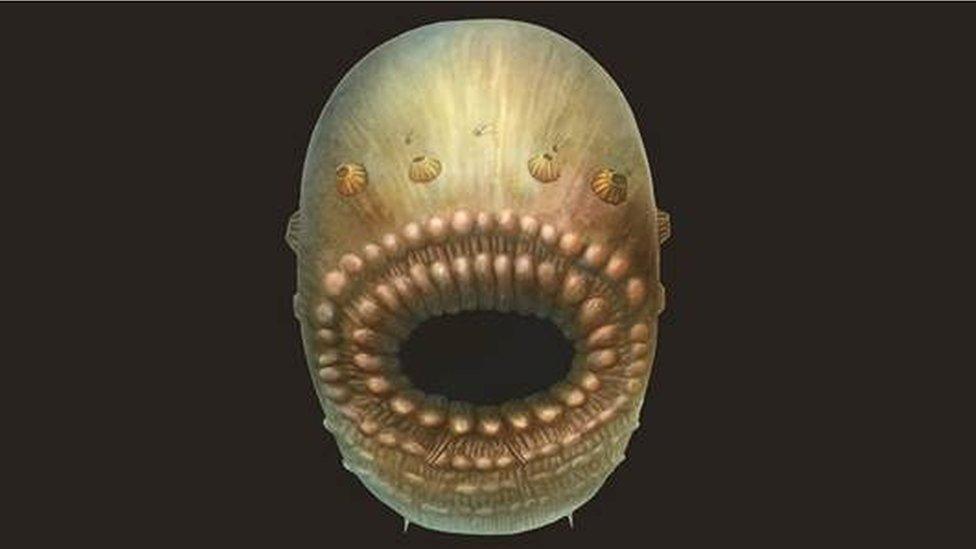

Artist's impression of the Gogo fish

Researchers have discovered a 380-million-year-old heart preserved inside a fossilised prehistoric fish.

They say the specimen captures a key moment in the evolution of the blood-pumping organ found in all back-boned animals, including humans.

The heart belonged to a fish known as the Gogo, which is now extinct.

The "jaw-dropping" discovery, published in the journal Science, was made in Western Australia.

The lead scientist, Prof Kate Trinajstic from Curtin University in Perth told BBC News about the moment she and her colleagues realised that they had made the biggest discovery of their lives.

"We were crowded around the computer and recognised that we had a heart and pretty much couldn't believe it! It was incredibly exciting," she said.

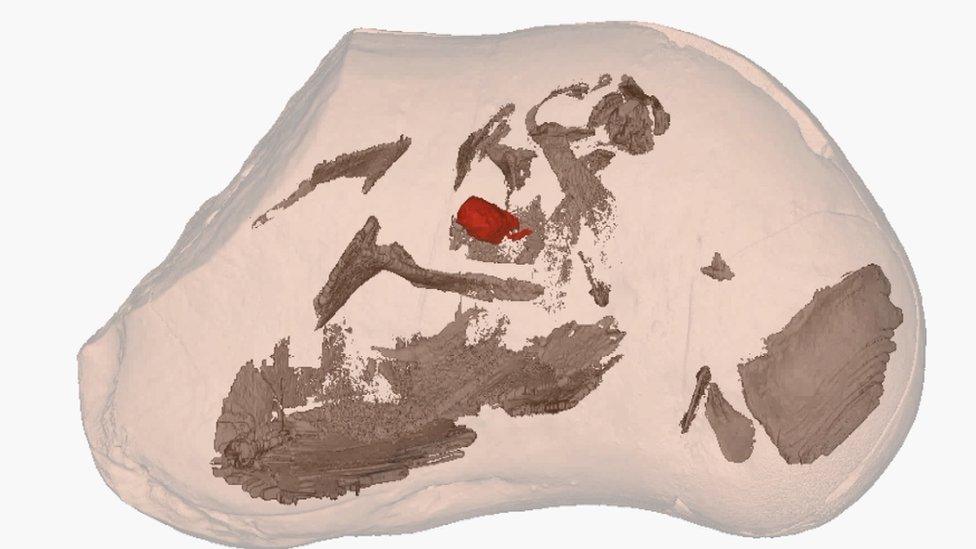

The fish are perfectly preserved in boulders found in the Kimberley region of Western Australia

Usually, it is bones rather than soft tissues that are turned into fossils - but at this location in Kimberley, known as the Gogo rock formation - minerals have preserved many of the fish's internal organs, including the liver, stomach, intestine and heart.

"This is a crucial moment in our own evolution," said Prof Trinajstic.

"It shows the body plan that we have evolved very early on, and we see this for the very first time in these fossils."

Her collaborator, Prof John Long from Flinders University in Adelaide, described the find as "a mind-boggling, jaw-dropping discovery".

"We have never known anything about the soft organs of animals this old, until now," he said.

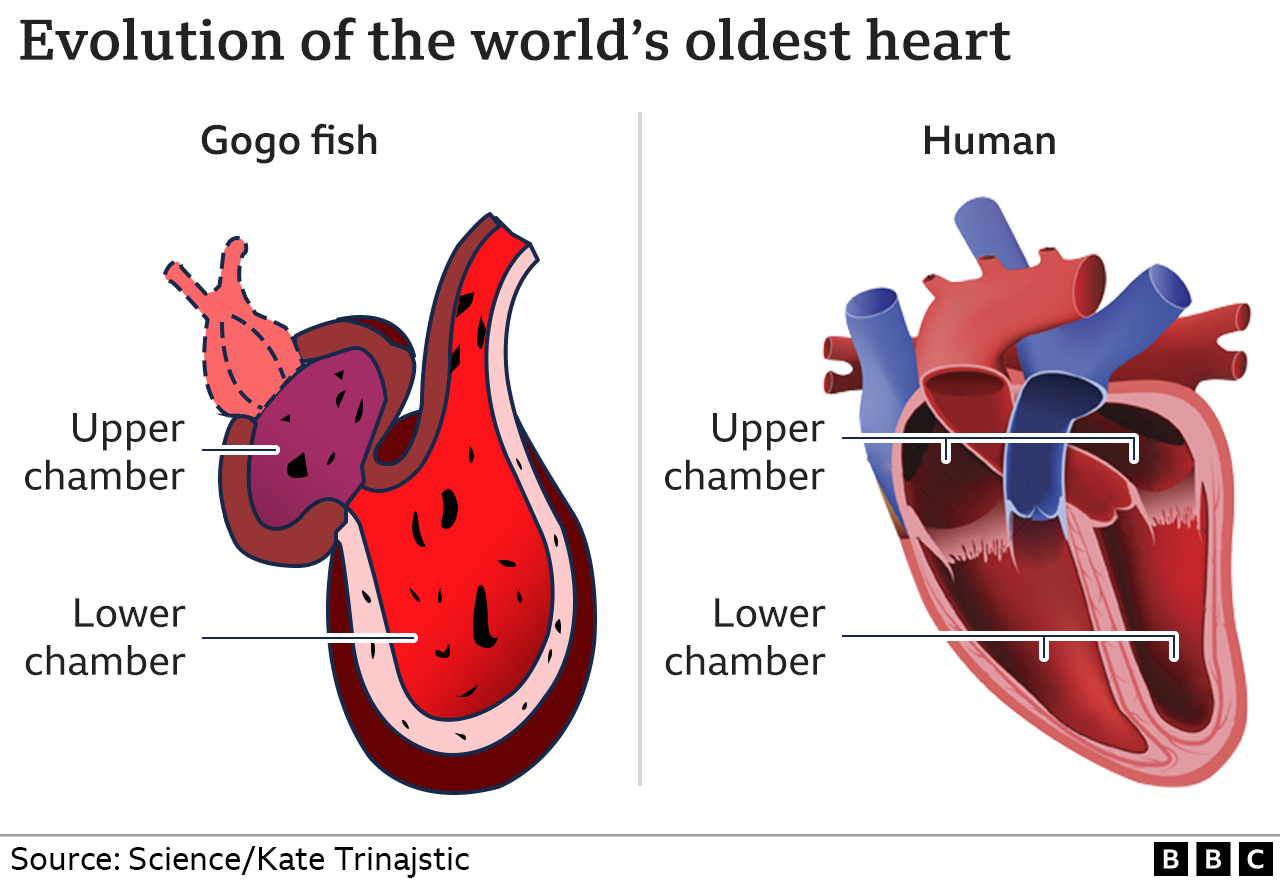

The Gogo fish's heart had two chambers, one above the other, which went on to evolve into the human heart

The Gogo fish is the first of a class of prehistoric fish called placoderms. These were the first fish to have jaws and teeth. Before them, fishes were no bigger than 30cm, but placoderms could grow up to 29.5ft (9m) in length.

Placoderms were the planet's dominant life form for 60 million years, existing more than 100 million years before the first dinosaurs walked the Earth.

Scans of the Gogo fish fossil showed that its heart was more complex than expected for these primitive fish. It had two chambers one on top of each other, similar in structure to the human heart.

The researchers suggest this made the animal's heart more efficient and was the critical step that transformed it from a slow-moving fish to a fast-moving predator.

The researchers scanned inside the boulders to discover a liver, stomach, intestines and a heart, shown in red

"This was the way they could up the ante and become a voracious predator," said Prof Long.

The other important observation was that the heart was much more forward in the body than those of more primitive fish.

This position is thought to have been associated with the development of the Gogo fish's neck and made space for the development of lungs further down the evolutionary line.

A fossil of the head of a Gogo fish with large eye sockets

Dr Zerina Johanson of the Natural History Museum, London, who is a world leader in placoderms, and is independent of Prof Trinajstic's team, described the research as an "extremely important discovery" that helps to explain why the human body is the way it is today.

"A lot of the things you see we still have in our own bodies; jaws and teeth, for example. We have the first appearance of the front fins and the fins at the back, which eventually evolved into our arms and legs.

"There are many things going on in these placoderms that we see evolving to ourselves today such as the neck, the shape and arrangement of the heart and its position in the body."

The discovery fills in an important step in the evolution of life on Earth, according to Dr Martin Brazeau, a placoderm expert at Imperial College London, who is also independent of the Australian research team.

"It's really exciting to see this result," he told BBC News.

"The fishes that my colleagues and I are studying are part of our evolution. This is part of the evolution of humans and other animals that live on land and the fishes that live in the sea today."

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

Related topics

- Published30 January 2017

- Published5 May 2011