How King Charles helped save British farmhouse cheese

- Published

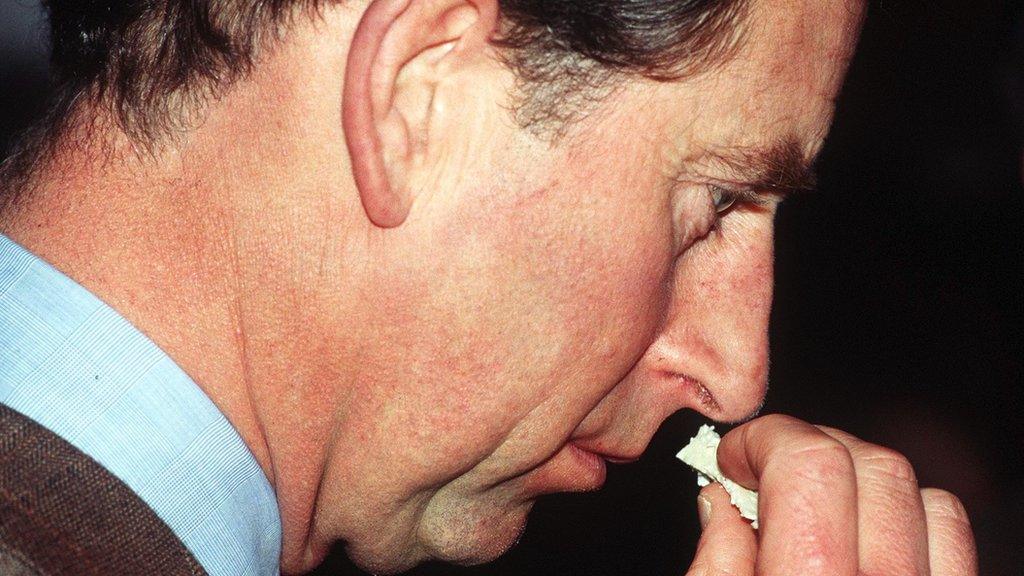

The Prince of Wales tasting traditionally made Cheshire cheese in 1995

King Charles III is famous for his support of environmental and social causes over the years, but did you know he played a decisive role in the renaissance of traditional artisan cheese in the UK?

It is a perfect example of the way he has used his position to help support the issues he cares about.

It may also hint at what a modern Carolean monarchy could look like.

The story begins back in the early 1990s when a series of food scares had shaken confidence in British food.

A raft of new hygiene rules designed for industrial cheesemakers was being applied to dairies producing farmhouse cheeses - including a potential ban on the use of unpasteurised milk.

Across the country artisan cheesemakers were teetering on the edge of bankruptcy.

Randolph Hodgson was worried, as he had spent the previous decade attempting to revive British cheesemaking by promoting the best produce through his cheese shop in London's Covent Garden, Neal's Yard Dairy.

"I really believed it would be the end of the great tradition of cheesemaking in the UK once and for all," he says.

Cheese matures at Neal's Yard Dairy in London.

Mr Hodgson had set up the Specialist Cheesemakers Association (SCA) to lobby for the interests of artisan producers and the association's work had caught the attention of the then Prince of Wales.

Cheese is only as good as the milk that goes into it and the prince was keen to support the high welfare and environmental standards on the dairy farms producing artisan cheese.

He was also interested in preserving traditional British farming and food productions skills.

He had become a patron of the SCA in 1993 and got wind of the troubles the industry was facing.

His response was typical of his approach to problems, say former advisers.

He decided to convene a meeting over lunch at Highgrove, his residence in Gloucestershire.

The King likes "connecting people and organisations in ways that open up possibilities and create solutions", explains his former press secretary Julian Payne.

"King Charles doesn't tell people what to do, but brings them together to see if they can work out a solution among themselves," he added.

The Prince of Wales tastes cheese in Preston in 2017

Charles invited cheesemakers and cheesemongers to his country pile along with civil servants from the Ministry of Agriculture and government ministers.

Mr Hodgson remembers the 1999 meeting well.

"Do we think it is important to keep these cheeses and traditions going?" Charles asked.

Everyone agreed it was.

"So, what are you going to do about it?" was his next question for the room.

The meeting ended with the civil servants agreeing to work with the cheesemakers to draw up a code of practice to ensure good hygiene in small dairies.

It was, says Mr Hodgson, an "incredibly important moment" in the history of British cheese.

"He wasn't seeking attention for his support, he just brought everyone together and found a path through it all," he remembers.

His intervention worked, says Tim Rowcliffe, a former chairman of the Specialist Cheesemakers Association.

"From that day on, we had a dialogue with authority rather than going to war," he says.

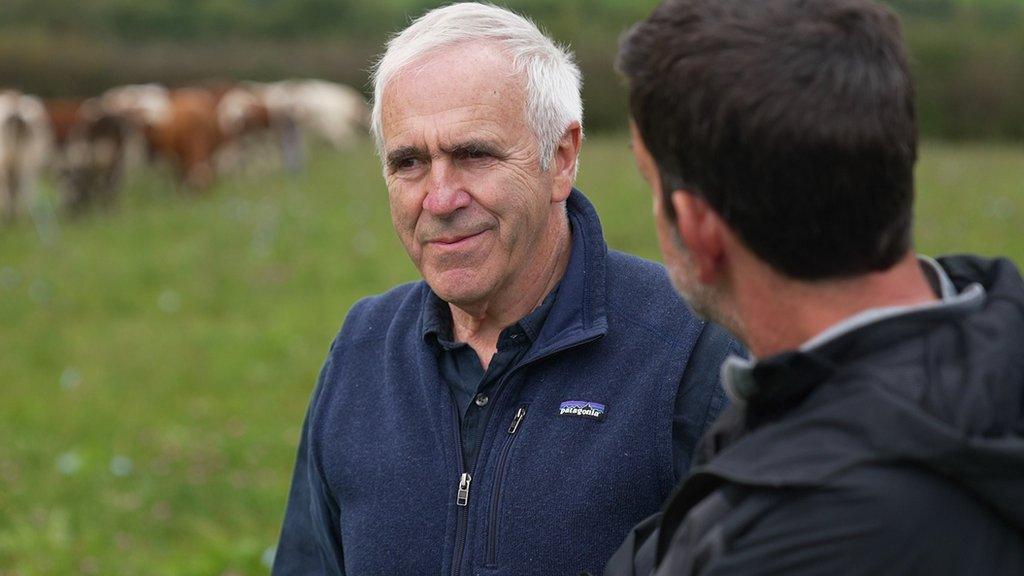

West Wales Cheesemaker Patrick Holden says his farm was saved by the efforts of King Charles III

And the industry has thrived.

Up in the hills of west Wales, I met Patrick Holden and his wife Becky who make a cheddar-style cheese called Hafod using unpasteurised milk from their 75 Ayrshire cows.

Patrick says his farm was saved by the efforts of King Charles.

"He saw the need for farmers to add value to their milk," explains Patrick, who says his farm is only viable because he can treble the value of his milk by turning it into artisan cheese.

Patrick is not alone.

There are now more than 700 different British and Irish farmhouse cheeses on the market: "Probably more than the French, dare I say it," laughs Mr Rowcliffe.

Artisan cheese has become a multi-million-pounds-a-year industry supporting hundreds of small farms, thousands of jobs and which now exports British cheese all over the world.

The King has quietly helped drive forward all sorts of other causes by convening meetings, building bridges, and just getting people talking together.

The rules have changed, of course.

Now he is King, Charles must remain politically neutral, but it is unclear if that will prevent him championing the causes he cares about.

He is planning a low-carbon coronation, for example.

Royal sources have confirmed to the BBC that deciding who will attend will be a "balancing act" between sticking to royal protocol and keeping the carbon footprint down.

Buckingham Palace may tell Commonwealth leaders they do not need to attend, to reduce the number of aircraft flying to London, for instance.

The King is also expected to use a state visit to France next month - the first of his reign - to highlight a scheme to plant millions of trees in Africa.

We understand he is unlikely to be promoting the virtues of British cheese during that trip, however.