COP29: Will rich nations promise more money for climate change?

- Published

A boy walks on the newly built sea wall that protects Jakarta from the rising sea levels

In 2009, the world's developed nations agreed to give $100bn (£78bn) a year to poorer nations by 2020 to help them tackle and prepare for climate change.

In the 15 years that have passed since that first goal was set, global temperatures have increased and emissions have grown - requiring trillions of dollars of investment, external to tackle the issue of climate change.

At the UN climate summit COP29 this year in Baku, Azerbaijan, countries will recommit to a new goal - but first they must agree how much will be given, who is contributing and how the money will be spent.

What do countries want money for?

Money for climate action broadly falls into three buckets:

Loss and damage

Two years ago, at COP27, world leaders agreed for the first time to establish a loss and damage fund.

This money is to help developing countries recover from the effects of climate change they are already suffering.

For example, in the past 12 months alone the developing world has experienced severe climate-related crises - from flooding in Myanmar to ongoing drought in East Africa.

It took decades to get this fund established because developed nations were wary of framing the payments as reparations and accepting liability for climate change on these terms.

Developing nations would like the new finance target to have sub goals where money is set aside for loss and damage and adapting to climate change - which historically has received a third of the funding of mitigation.

Mitigation

This is money to help developing nations move away from fossil fuels and other polluting activities. This is where most money has been given to date because it can often be profitable.

Many countries still have coal power stations that are yet to reach the ends of their lives. They need support to switch to clean energy, such as solar farms.

Adaptation

This is money to help developing nations prepare for the worst effects of climate change.

It is different to loss and damage as it is focused on the future.

The needs vary depending where in the world the country is, but may include:

building stronger flood defences

relocating populations at risk

developing storm proof housing

distributing crops that are more resilient to dry spells

What has been given so far?

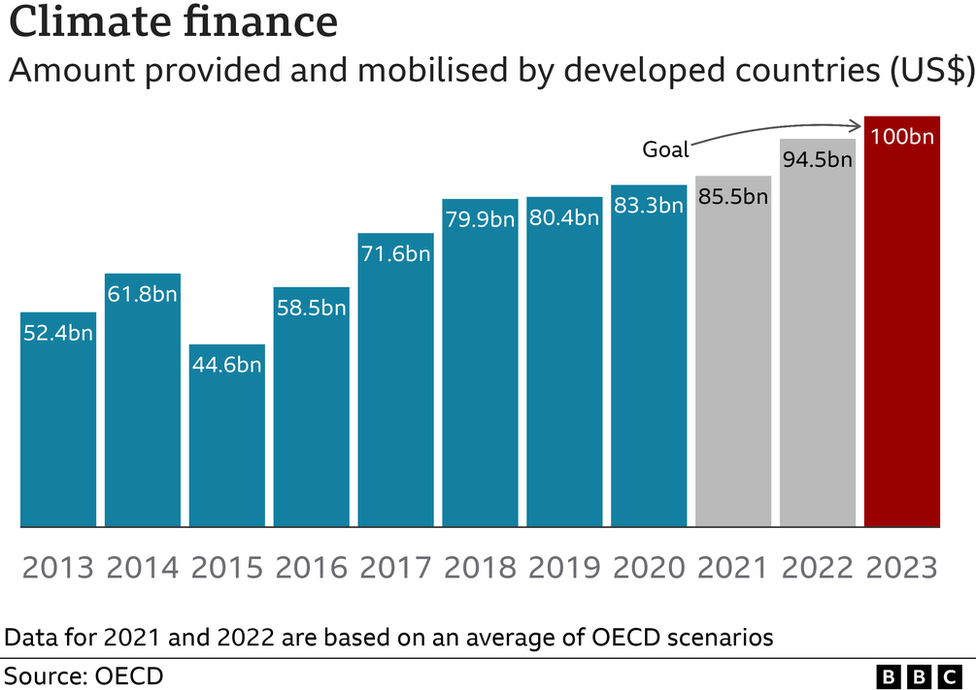

In 2009, richer countries agreed to provide $100bn (£78bn) a year to developing nations for climate action by the end of 2020.

But by the end of that year the total was $83.3bn (£65bn) - the goal was finally reached three years later.

The majority, 82%, of this money came from public funds, with the remainder from the private sector, according to the OECD, external.

But analysis, commissioned by the UN, external, suggests the private sector could deliver 70% of future investments needed to meet climate commitments. A coalition of more than 550 private firms have already committed, external to use $130tn of assets to help achieve net zero.

One study in 2018, external estimated that developing countries would suffer between $290bn - $580bn (£226bn - £451bn) in damages by 2030, another put the cost at $400bn, external (£311bn). It is difficult to predict the exact amount, but it is clear the current size of the fund is too small to tackle the issue.

What might countries agree in Baku at COP29?

Negotiations on the new quantified goal have been happening for months between governments.

At the heart of these talks is how much money should be given.

Many studies have tried to put a figure on it - the G77+ China alliance of developing countries has previously said at least $1.3tn (£1.14tn) needs to be mobilised by 2030.

A UN committee on finance, external tried to combine all these estimates and earlier this year put the number as high as $6.9tn.

It is unlikely a figure in that region will be announced at Baku. Developed nations including the UK, have recently raised concerns they may not meet their previous pledges because of ongoing domestic economic issues.

Another key area of discussion is how the money will be given - the majority of the public funding, 69%, is still given in the form of loans rather than direct grants, external. This can increase the debt burden in poorer nations.

Nafkote Dabi, Oxfam International Climate Policy lead, has called this "profoundly unfair".

He said: "Instead of supporting countries that are facing worsening droughts, cyclones and flooding, rich countries are crippling their ability to cope with the next shock and deepening their poverty."

The third big question on the table is who will contribute. Thirty years ago, it was agreed that developed countries should take on more of the financial burden because of their historical contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, and the economic benefits they enjoyed from exploiting fossil fuels.

But since then, developing nations like China have grown economically and have a larger carbon footprint. Countries like the US would like China to not just voluntarily give money but be required to.

- Published28 October 2024