Nasa's Artemis Moon rocket lifts off Earth

- Published

Watch: Nasa's Artemis I rocket blasts off

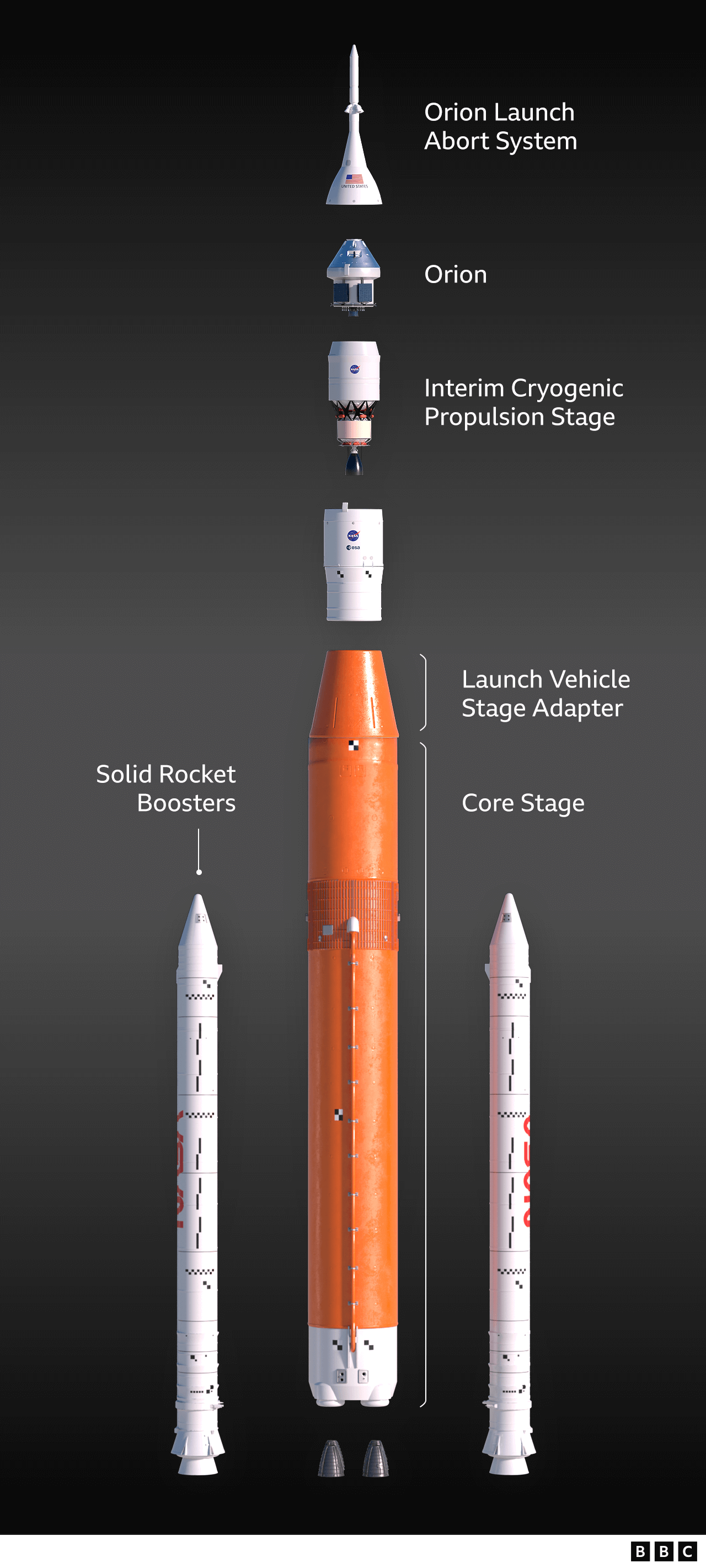

The American space agency Nasa has launched its most powerful ever rocket from Cape Canaveral in Florida.

The 100m-tall Artemis vehicle climbed skyward in a stupendous mix of light and sound.

Its objective was to hurl an astronaut capsule in the direction of the Moon.

This spacecraft, known as Orion, is uncrewed for this particular flight, but if everything works as it should, people will climb aboard for future missions that go to the lunar surface.

Wednesday's flight followed two previous launch attempts in August and September that were aborted during the countdown because of technical woes.

But such issues were overcome on this occasion, and the Space Launch System, as the rocket is often called, was given the "go" to begin its ascent from the Kennedy Space Center at 01:47 local time (06:47 GMT).

"Today, we got to witness the world's most powerful rocket take the Earth by its edges and shake the wicked out of it," said Mike Sarafin, Nasa's Artemis mission manager. "We have a priority one mission in play right now."

His boss, the agency's administrator Bill Nelson, was also wowed.

"That's the biggest flame I've ever seen. It's the most acoustical shockwave that I have ever experienced," he commented. "I have to say what we saw tonight was an A+. But we have still a long ways to go. This is just a test flight."

The rocket had a number of important manoeuvres to perform high above the planet to get the Orion capsule on the right path to the Moon. All were performed "outstandingly", said John Honeycutt, Nasa's SLS programme manager.

The ship will now rely on its European propulsion module to shepherd it safely on the rest of the mission.

Josef Aschbacher is director general of the European Space Agency (Esa): "We have to make sure that Orion is powered safely to the Moon, circles the Moon, and then, as you know, we have to bring it back safely to Earth, making sure that the entry of the capsule into the atmosphere is on the right trajectory and at the right angle so that it can land in the Pacific Ocean. Yes, our job starts now, and it's a huge responsibility."

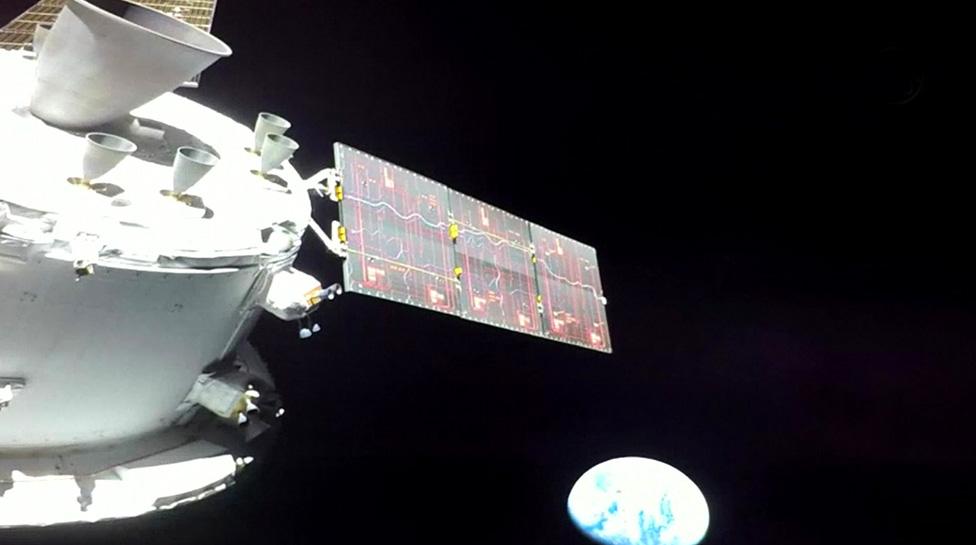

The Orion capsule looks back towards the Earth

December will see Nasa celebrate the 50th anniversary of Apollo 17, the very last time humans walked on the Moon.

The space agency is calling its new programme Artemis (Apollo's twin sister in Greek mythology).

It's planning a series of ever more complex missions over the next decade that should result in a more sustained presence at Earth's satellite, with the presence of surface habitats and the use of rovers, together with a mini space station in orbit around the Moon.

Nasa hopes Artemis will become an inspiration to a new generation. It has promised that women and people of colour will feature in these endeavours, something that didn't happen 50 years ago.

"I wanted to be an astronaut from the time that I was five years old," said astronaut Jessica Meir. "For anybody that has a dream or some kind of aspiration, if they see somebody that they can identify with a little bit, it puts them into a totally different perspective where they can say, 'Well, wait a minute, that person was just like me, and they did it so I can do it, too'."

In 1972, Apollo astronaut Gene Cernan left the last set of footprints on the Moon. As he departed from the lunar surface, he said he believed it wouldn't be long before we returned. It's been 50 years. But today, the Moon is within reach for humanity once again.

With a roar of its mighty engines, Nasa's new rocket has lifted us into a new era for human spaceflight.

Nasa's astronauts watched on - if this mission is a success, next time they will be onboard, first flying around the Moon, and then landing on it.

But we're not there yet. The Orion spacecraft may be on its way, but it has more than a million miles of travel ahead. It has to reach the Moon, orbit around it, and then return home. Nasa has to show this system is safe before any astronauts can be strapped in for the ride.

Orion is being sent on a 26-day excursion that will take it into what's called a distant retrograde orbit at the Moon.

At its closest, the capsule will be a mere 130km from the lunar surface; at its most distant, Orion will be up to 70,000km (45,000 miles). This will be the furthest from Earth any human-rated spacecraft has ever ventured.

The capsule is due back on Earth on 11 December - about three and a half weeks from now.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

That's when one of the key events in the whole mission occurs.

Engineers are most concerned to learn that Orion's heatshield will cope with the extreme temperatures it will encounter on re-entry to our planet's atmosphere.

The capsule will be coming in very fast - at 38,000km/h (24,000mph), or 32 times the speed of sound.

A shield on its underside must cope with temperatures approaching 3,000C.

Artwork: The upper-stage of the rocket put the Orion capsule on a path to the Moon

The rocket headed high and east from Kennedy, out over the Atlantic Ocean

The United Kingdom is playing its part in the Artemis adventure, and not just as a member state of the European Space Agency.

On Wednesday, the Goonhilly Earth Station in Cornwall picked up the Orion ship's radio signal as it came off the top of the rocket. By analysing the shift in frequencies as the capsule moved through space, it enabled Nasa to more accurately calculate the trajectory for a later course correction.

Goonhilly will be sending commands to six of the 10 small satellites that were also lofted by the SLS rocket.

"We started our company here less than 12 years ago with an ambition to do deep space communication," explained Goonhilly CEO Ian Jones.

"We thought we'd be picking up scraps here and there by now, not to be actually commanding spacecraft on Nasa's first return to the Moon, which is brilliant."

Goonhilly tracked the Orion capsule across the sky, helping Nasa to work out its exact path

Goonhilly will also be sending commands to small satellites launched with Orion

Huge crowds gathered in and around the Kennedy Space Center to watch the launch

The SLS produces 39 meganewtons, or 8.8 million pounds, of thrust off the pad