Citizen scientists join fight to clean up rivers

- Published

Citizen scientist John Pratt collects a sample for testing from the river Evenlode

The past year has seen public anger over pollution in rivers and waterways.

According to the environmental charity Earthwatch, people are increasingly taking pollution monitoring into their own hands.

John Pratt used to go fishing on the Evenlode which flows through the Cotswold Hills. Now he takes a chemistry set.

A local resident for 33 years, the river has become part of his life.

So when one summer the crystalline waters resembled soup, he was determined to take action.

Some might join a protest or post images of polluted rivers on social media, but John became a citizen scientist. He's one of many up and down the country hoping their data will help in the effort to clean up rivers.

Local patrols are keeping an eye on everything from plastic pollution to declining fish

During the year, thousands of people have taken part in protests over sewage spills in rivers and on beaches from Essex to Edinburgh. And at the same time, there's been a boom in citizen scientists turning their attention to the health of the nation's waterways.

The UK has seen a long tradition of the public getting involved in scientific research, including tracking the numbers of plants, birds and insects.

But as more people spend time out on the water paddle-boarding or wild swimming, there's growing interest in sounding the alarm on pollution, from plastic to chemicals.

English Channel swimmer Peter Green holds a protest action against the dumping of raw sewage into the sea

Earthwatch, which trains citizen scientists, says the number of community groups carrying out monitoring for chemical pollutants has doubled in the past year alone. And on this stretch of the Evenlode, there are now more samples taken by citizen scientists than anyone else.

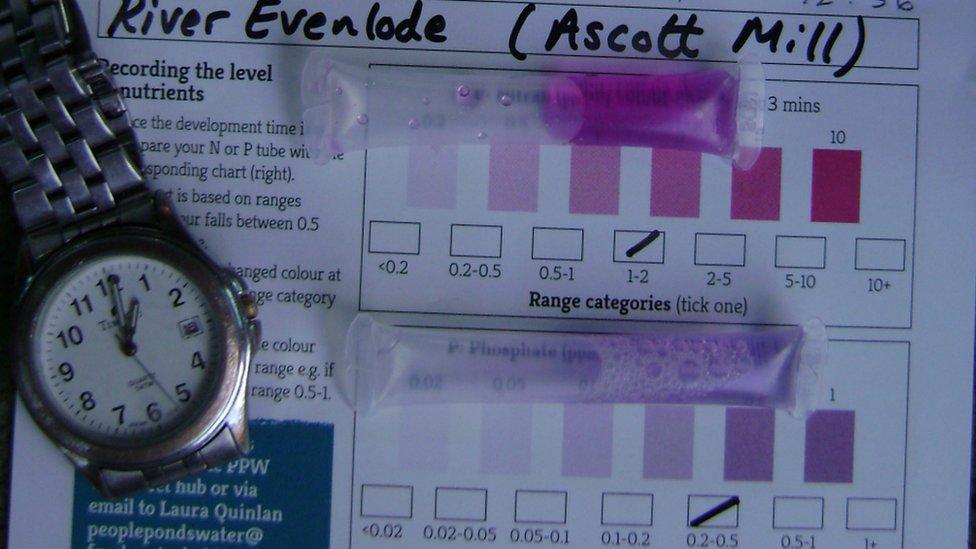

Earthwatch trains volunteers like John Pratt to test for nitrates and phosphates - chemicals found in fertiliser, sewage and farm slurry.

These are naturally present in small quantities but in excess can cause vast blooms of algae and kill fish and invertebrates.

The data John collects on the Evenlode helps scientists and regulators build up a better picture of how pollution levels change over time.

"I'm just one of many citizen scientists who are concerned with the health of the river," John explains, looking out over this area of outstanding natural beauty near Charlbury.

"We hope through dialogue and through action by the water utility it will be possible to restore the Evenlode to the health it had before the year 2000."

The River Evenlode flows for 45 miles (72km) from Gloucestershire to the River Thames

The Evenlode meanders to join the Thames through picture-perfect towns. The early 20th Century poet Hilaire Belloc wrote of the "lovely" Evenlode and how it bound his heart to English ground.

Yet today the river is plagued with pollution, causing weed growth, declining fish and insect numbers, and cloudiness for much of the year. It is not alone.

According to a report by Environmental Audit Committee MPs, England's rivers are "in a mess", contaminated by "a chemical cocktail" of sewage, agricultural waste and pollution.

Monitoring regimes were described as "outdated, underfunded and inadequate".

Data on nitrates and phosphates - chemicals found in fertiliser, sewage and farm slurry

Dr Heather Moorhouse of Earthwatch says citizen scientists can't replace the work of regulators but they can put pressure on polluters to clean up their act.

"Citizen science is plugging an information gap and helping our understanding of water quality in our rivers," she says.

"But this data needs to be used to hold polluters to account and to invest in improvements to the way our rivers are managed."

John Pratt and Dr Heather Moorhouse test a river sample for pollutants

The main problem for the Evenlode, like many rural rivers, is pollution from sewage and agricultural waste, says Dr Izzy Bishop, a lecturer in ecology at UCL in London.

And the "huge boom" in people collecting data through citizen science is helping to keep the problem of river pollution on the political agenda.

"The visibility and transparency of data that is being collected by the public is one of the big drivers for pushing this up the political agenda," she says.

People gather on Tankerton beach in Kent to protest against sewage discharges

As for John, he hopes that one day he'll be able to relive his childhood memories.

"We all share childhood memories in the summer time of taking our shoes and socks off and paddling in streams and rivers and being able to see our toes when we're waded up to our knees," he says.

"It is possible on some of our tributaries, it's possible on some of the burns up in Scotland, it's possible on some of the streams in Wales but in our poor river Evenlode that is no longer possible."

Follow Helen on Twitter @hbriggs.