Meteosat: Europe's new weather satellite heads skyward

- Published

A daylight launch which also despatched two telecommunications satellites

The most important European satellite of 2022 has just gone into orbit.

Meteosat-12 rode out of the Kourou spaceport in French Guiana on an Ariane rocket to initiate a new era in weather forecasting.

The spacecraft will image the atmosphere over the European continent, the Middle East and Africa.

The data it acquires with its next generation technologies promises to greatly enhance our ability to track the emergence of violent storms.

"Look at the storm that impacted in Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium last year where over 200 people lost their lives. These events are tragic," said Phil Evans, the director general of Eumetsat, the inter-governmental organisation that manages Europe's weather satellites.

"More accurate, frequent and relevant observations from space are absolutely essential to provide better forecasts and warnings which help us reduce and mitigate the impacts of these severe weather events."

The Ariane's lift-off from Kourou occurred at 17:30 local time (20:30 GMT), with Meteosat-12 ejected just over half an hour later.

It will take some time to get it properly into position 36,000km above the equator, and it will be a year before its observations are fully integrated into forecasting models.

But once this is achieved, the benefits should become obvious.

Your device may not support this visualisation

Europe has had its own meteorological spacecraft sitting high above the planet since 1977. The new imager that's just gone up is the third iteration in the series.

Meteosat-12 will return a full picture of the weather below it every 10 minutes, five minutes faster than is currently the case. It will be able to see even smaller features in the atmosphere, down to 500m across, and view them in more wavelengths of light.

National forecasting agencies such as the UK Met Office and Meteo France will see a big jump in the amount of data they receive.

BBC Weather presenter Matt Taylor: "We can see the whole globe"

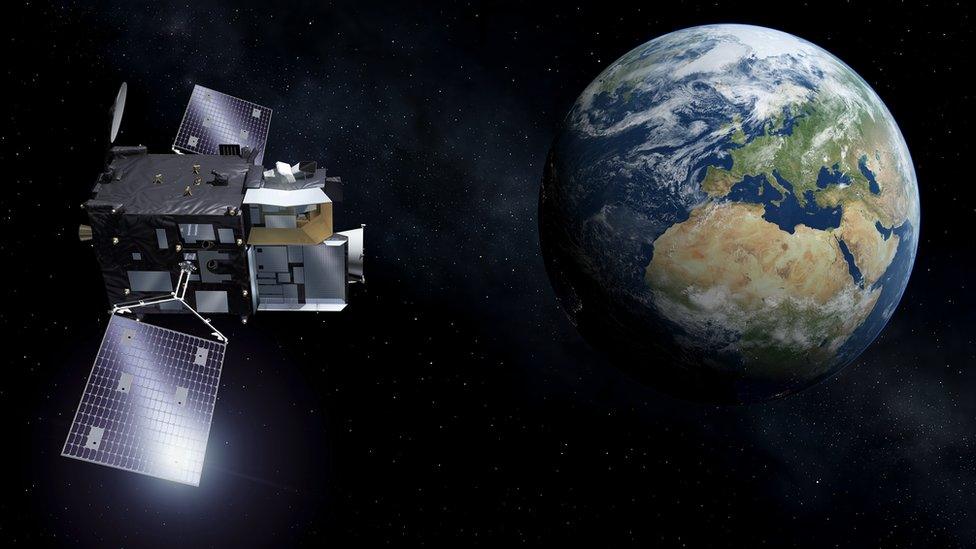

Artwork: The near-4 tonne satellite will sit 36,000km above the equator

One of the major innovations is the inclusion of a camera to detect lightning. The agencies believe this will be a boon to what they call "nowcasting" - the ability to track and forewarn of imminent, hazardous events. That's because lightning is a tracer for violent wind gusts, heavy precipitation and hail.

It's long been possible to track lightning from its radio frequency emissions, but these are largely air to ground strikes, and 90% of lightning is air-to-air, or intra-cloud.

"The new Meteosat instrument is set to be a game-changer," said Simon Keogh from the UK Met Office. "It will give us a much better handle on total lightning. That's something we need to know if we're forecasting for helicopter operations in the North Sea, for example. Likewise, if there are hazardous materials being unloaded from aircraft, even passengers, we need to know if there is a lightning risk," he told BBC News.

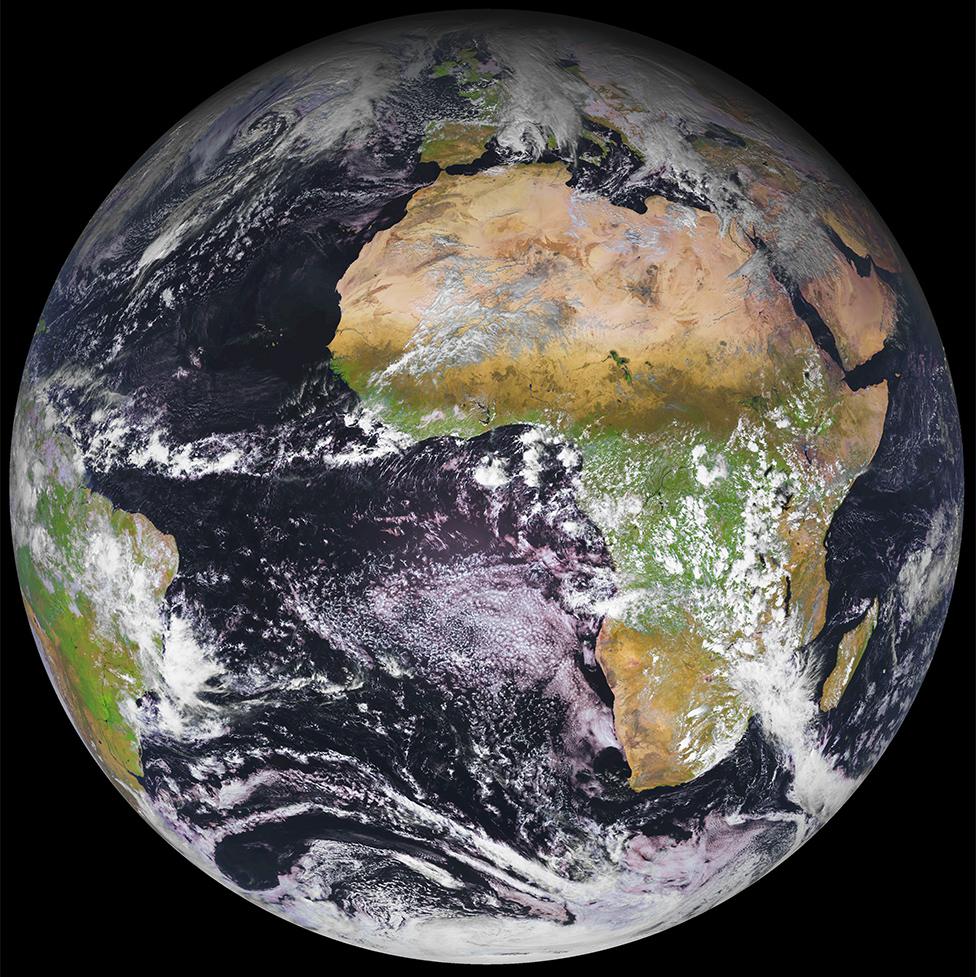

A full disc image of the Earth will be returned every 10 minutes

The new generation system will eventually see three spacecraft working in unison.

A second imager will go up in 2026 to acquire more rapid - every 2.5 minutes - pictures of just Europe. Before that, in 2024, a "sounding" spacecraft will launch to sample the temperature and humidity down through the atmosphere.

With replacement satellites already ordered for the first working trio, Europe is guaranteed coverage well into the 2040s.

This capability doesn't come cheap. Member states of the European Space Agency (Esa) have funded the research and development to the tune of €1.4bn (£1.2bn). Eumetsat nations are picking up the ongoing costs expected to be €2.9bn (£2.5bn).

The inclusion of a lightning imager is set to be a game-changer

"It's a long process with trade-offs," said Paul Blythe, who's steered the Meteosat development for Esa.

"Some of the detector elements and the optical elements that we have on board have taken six, seven, eight years to bring to fruition from the initial setting of the requirements through lots of development work and finally getting the product to build into the satellite. After that, we have to qualify the whole system. It isn't a quick activity.

"We will benefit from an economy of scale by buying six satellites at once. If you only buy three or four then it's clear the next generation will cost even more."

If €4.3bn (£3.7bn) still sounds like a lot of money, it is worth recognising the returns that stem from good weather forecasting.

In giving the public the confidence to go about their daily lives, in helping to reduce accidents on the roads, or enable sectors such as aviation and shipping to operate more efficiently - there is a clear added value to the economy that repeated analyses have judged to be worth billions every single year.

Six satellites have been procured in bulk. It means one or two will stay in storage for perhaps 10 years