The Amazon reef that may be threatened by oil drilling

- Published

The reef is mostly made of hard red algae, providing an attractive habitat for marine life such as this moray eel

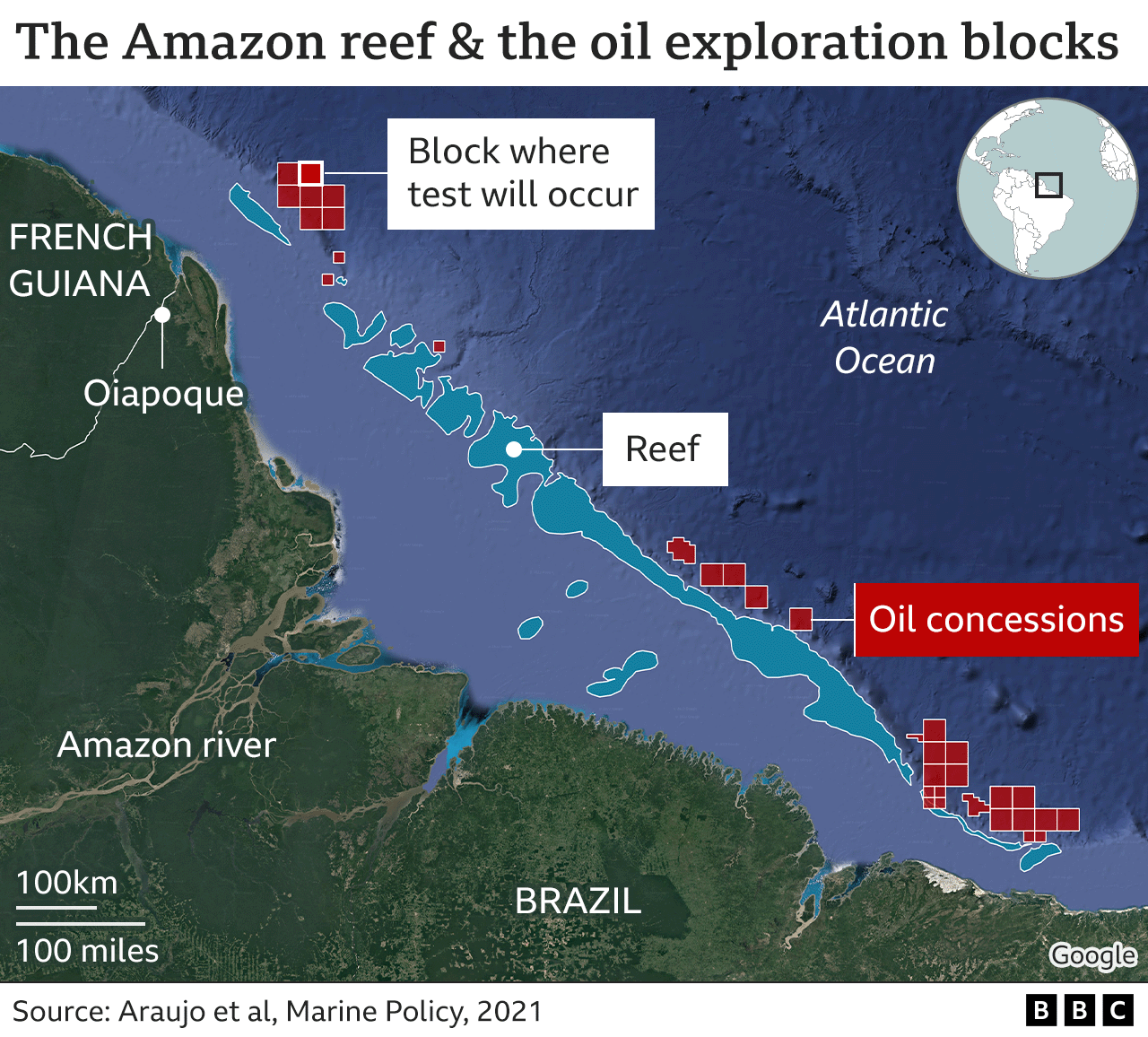

Scientists say a unique reef habitat near the mouth of the Amazon river is under threat from plans to drill for oil. The reef was discovered in 2016, and researchers say it could contain many unknown species of medicinal or scientific value.

The Amazon reef is unusual because it lies in deep water, and is sometimes hidden by the muddy waters flowing into the sea from the world's largest river.

Its depth - up to 220m (725ft) and the strong currents in the area mean that it has been little studied since it was discovered.

"It's a very wide area, there are things that we don't know yet," says César Cordeiro, a professor at the Center for Biosciences and Biotechnology at the University of Northern Rio de Janeiro.

"There are species that may be appearing only in that area and nowhere else in the world."

One is a sponge currently being studied at the University of São Paulo, which has shown signs of possessing anti-cancer properties.

"There is great potential for economic gain with the study and protection of these systems," says Rodrigo Leão de Moura, professor at the Institute of Biology at the University of Rio de Janeiro and the leading scientist involved in the reef's discovery.

"Of course, we have this immediate need for cheap energy, but how much does this sacrifice a future based on biotechnology?"

The scientists worry that plans by the Brazilian oil company Petrobras to drill for oil close to the reef could cause an oil leak that would devastate the ecosystem.

Petrobras is planning this month to carry out a test to learn more about how oil would be dispersed in the case of a leak.

If that satisfies Brazil's environmental protection agency, Ibama, exploration wells could follow soon afterwards, 160km (100 miles)from the shore, but much closer to the reef.

Brazilian Environment Minister Joaquim Leite - a member of the outgoing government appointed by President Jair Bolsonaro - has said it is possible to explore for oil there and protect the environment, but Prof Moura has doubts.

"This area has one of the strongest currents on the planet and a tidal range that can be greater than 10m (33ft). These are environmental conditions that challenge any engineering work, making it very risky," he says.

Many reefs occur in shallow water, where the sun provides abundant energy for corals to grow.

This one is different. It is deeper and gloomier, and is mainly composed of hard red algae capable of carrying out photosynthesis - the process by which plants turn sunlight, water and CO2 into carbohydrates and oxygen - in low-light conditions.

"They are red algae that use light in a more filtered way - they use the blue spectrum of light," says Prof Moura.

The reef is deep and lies below murky water flowing out of the Amazon

The algae are hard because they contain a chalk-like substance in their cell walls, and this allows large solid structures to grow over time.

The reef is thought to cover an area of 56,000 sq km (22,000 sq miles) and to shelter many different sponges, some corals, and at least 70 species of fish, shrimp, and lobster. These in turn provide a source of food and income for thousands of families on the Brazilian coast, some of whom are also concerned about Petrobras's plans.

Fisherwoman Darcirene Garcia worries that the disturbance created by the oil company's ships will drive fish away: "They will go further out, and in our small boats we will not be able to go after them."

An oil spill that hit the coast of northern Brazil in 2019 also casts a long shadow. Tons of thick black crude began washing up at a thousand locations, and brought the tourism industry to a halt. Overnight the biggest market for locally caught fish disappeared. Other buyers stopped buying too, for fear of contamination, so sales fell by 80% or 90% says Carlos Pinto, of the seaworkers' union, Confrem.

Oil washed up along Brazil's northern coast in 2019

Darcirene Garcia took part in a meeting with Petrobras on 8 November, along with other members of the fishing community in Brazil's most northerly town, Oiapoque.

"It seemed to be ready-made answers," she says. "Whatever we asked, their answer was always: 'It is too far from the coast.' At the end of the meeting, the fishermen shouted together, saying that they were against the drilling, but they didn't say anything."

Petrobras says it is holding meetings with communities that could be affected by the project, in order to "clarify doubts and expectations".

Oil discoveries along the coast of countries to the north-east - Suriname and Guyana - have heightened expectations of important oil reserves off the Brazilian coast.

Petrobras signalled on 1 December that Brazil's northern coast would be a priority over the next five years, attracting half of the company's $6bn exploration budget over this period. But it is unknown whether the incoming government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva will back the plan to drill near the reef.

His party's spokesperson on the environment has indicated her opposition, but the last time Lula was in government he relied on the revenue from oil finds in the Santos Basin south of Rio de Janeiro to fund social programmes.

The reef helps to ensure an abundance of fish on Brazil's north coast

Professors Rodrigo Moura and César Cordeiro see the reef's biodiversity as one of its main benefits, but also point out others.

One is that it provides a more sustainable source of income than many other local industries.

"If people cannot fish, they will have to find another source of income, and what is there in the Amazon to do?" Prof Moura asks. "Hunting, deforestation, opening of pastures, migration to forest areas?"

Another is that it operates as a carbon sink.

The hard cell walls of the algae contain calcium carbonate, Prof Cordeiro points out, thus helping to remove carbon from the atmosphere for an indefinite period.