Can the UK's race to space take off?

- Published

This rocket will deliver satellites into orbit - the first time this has happened from British soil

The first-ever orbital rocket launch from British soil is set to blast off on Monday, marking the start of the UK's race to space.

The ambition is to turn the country into a global player in space - from manufacturing satellites, to building rockets and creating new spaceports. But can the UK carve out a place in an increasingly crowded market - and why try to reach for the stars?

"We are the guinea pigs," says Melissa Thorpe.

"It is the first time any of us have done this, so it's been quite a learning experience."

WATCH: The BBC got an exclusive look inside Virgin Orbit's rocket launcher

Melissa is in charge of Spaceport Cornwall, which is about to attempt its very first foray into space.

She's showing me around their base at Newquay Airport.

There's all the usual hubbub of activity: passengers arriving, suitcases being loaded, planes being fuelled.

But there's also something more surprising on the tarmac: a 21m-long rocket.

A team is busy prepping it for the first ever launch from UK soil that will take satellites into orbit around the Earth.

The Cornwall rocket launch will begin its journey to space on this modified jumbo jet

But this is a blast off with a difference.

There won't be a vertical launch from the ground. Instead, the rocket is fixed underneath the wing of a modified jumbo jet. Once the plane is mid-air, the rocket will be released and fire its engines to head into space.

Setting up the UK's first spaceport has taken years and a lot of hard work, plus an entirely new regulatory framework to ensure these launches are safe.

The hope is it will make a difference to the local area, one of the poorest in the UK, by bringing in new companies and creating new jobs.

"I think it's the next chapter for Cornwall," Melissa says.

"We were at the heart of the Industrial Revolution. We're not new to pioneering technologies."

But there's a wider ambition too. If this succeeds, it should help to position the UK as a leading place for space.

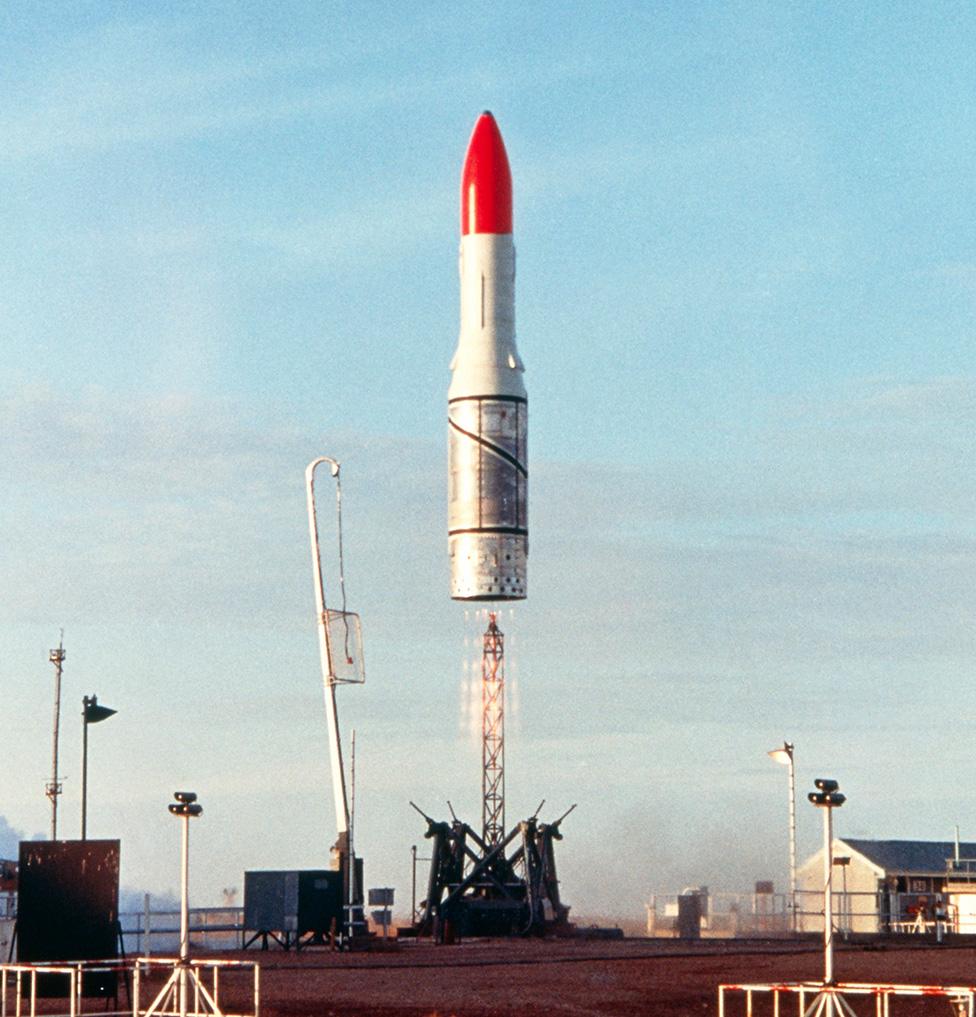

The "lipstick" rocket should have marked the start of the British launch industry

However, this isn't the first attempt at creating a British launch industry.

A white and red rocket, nicknamed "the lipstick", was supposed to be the start of something big for the UK.

It blasted off in 1971, sending a satellite into space.

The programme was called Black Arrow, and this was the first British-built rocket to deliver a British-built satellite into orbit - although it took off from Australia.

But the costs were deemed too high by the government, so that first launch turned out to be the last.

The UK's launch industry hit a long pause after this, but another aspect did take off in Britain - satellite building.

And this has helped to drive a thriving space sector, which, according to a recent government report, external, is worth £16.5bn a year to the UK economy and employs nearly 50,000 people.

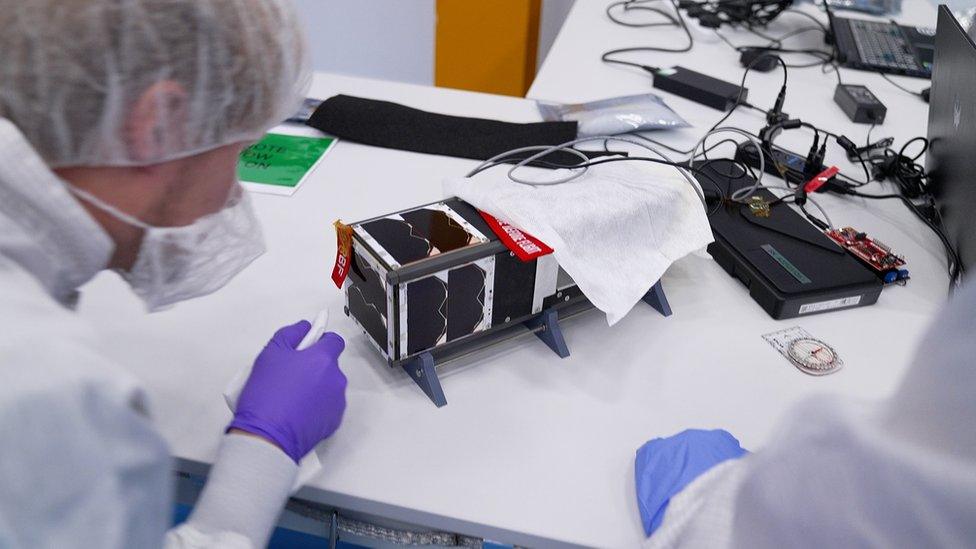

Nine small satellites will be sent into space from Cornwall

"We absolutely knock it out of the park when it comes to small satellite manufacture," says Dr Alice Bunn, President of UKSpace, the trade association of British space companies.

Until now, she says, satellites built in the UK have had to be shipped abroad to get into space, but this first launch will change that.

And it comes at a time when satellites have become integral to our lives - although Alice says most people are unaware of how dependent we are on this technology.

"Think about satellite navigation systems, environmental monitoring, emergency response - let alone all the telecommunications capability - that we can provide from space. It really is a running thread through our lives," she says.

And some companies have big plans with this technology.

Welsh company Space Forge want to use satellites to make materials

The Cardiff-based company Space Forge thinks a whole host of new materials can be made in orbit.

In a cleanroom, one of their small satellites is being painstakingly prepared for its journey. It's one of nine being sent into space by the Cornwall launch.

Space Forge describe their shoe box-sized satellites as mini factories.

"In space, with the absence of gravity, you can mix together any different materials you want," says Chief Technology Officer Andrew Bacon.

"So if you take the whole periodic table, and start putting things together - like lead, aluminium, rubidium, einsteinium - there are billions of new alloys that you can now make that you couldn't make on Earth."

The new materials could be used in electric vehicles, green technology or computing, he explains.

And he thinks there are some big advantages to launching these satellites close to their Welsh base.

''The fact that we can just drive down the road for a couple hours to get to our spaceport is a huge impact," Andrew says.

The Saxavord Spaceport is located on the northernmost tip of Unst, one of the Shetland Islands

But it's not just Cornwall racing to space.

Amidst the bleakly beautiful undulating hills and jagged cliffs of the Shetland island of Unst, there's a hive of activity as diggers and dumper trucks come and go.

The team here is celebrating because an important milestone has been reached. The concrete is setting on their first launch pad, one of three planned at the site.

The SaxaVord Spaceport is being constructed on a peninsula jutting out into the sea, at the northernmost tip of the UK.

The SaxaVord team is building a new launch pad at the site

"I think the first response from the locals was that maybe it was an April Fool or something like that," says Debbie Strang, SaxaVord's chief operating officer.

"And then, as they've seen the progress and the development, there's been real excitement about what we've been doing."

There's a good reason why they've chosen such a remote place, where sheep and Shetland ponies outnumber the inhabitants.

"It's the safety element for us," says Debbie.

"What we're doing needs to be as far away as possible from population centres, so that when the rocket leaves, there's no real danger to people nearby."

The remote site is located far from densely populated areas

SaxaVord is aiming for the UK's first vertical rocket launch to take satellites into orbit, with up to 30 launches a year once it's fully up and running.

It's not the only spaceport to be based in Scotland. Others are planned in Sutherland in the Highlands and Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides.

The hope is that these could all boost local economies, and that's especially important in Unst.

"This island's suffered quite badly from depopulation over the last 20 or 30 years," explains Scott Hammond, the deputy CEO of SaxaVord.

"There was a small airfield here that used to be the third busiest heliport in the UK. And then they also had an RAF station here.

"When that left, it halved the population of the island and it clearly had a massive economic impact."

He hopes the spaceport could give the island a boost.

"We'll have more and more service jobs, during the fuelling of the rockets, for example, putting the liquid oxygen into the rockets. And those of course, will be highly paid, highly skilled jobs."

Aerospace graduate Ahsan Zaman says the UK's space industry is creating new opportunities

But if you're building a launchpad, you also need rockets - and SaxaVord is working with several companies looking to use Unst to blast off.

One of these is Skyrora, based in Cumbernauld, just outside of Glasgow.

Inside their vast hanger, the team is busy working on different rocket parts, from nose cones, to engines and containers for propellants.

The company is making smaller prototypes, before building a larger rocket, Skyrora XL, that they plan to eventually launch from the Shetland Islands.

Skyrora is working on a prototype rocket before it builds a larger model

"You do a full design on paper and then you start building it. You build prototypes, you do tests, you go back to the drawing board and see what needs to be fixed," says Ahsan Zaman.

He's just finished his aerospace degree, and says the new push for space in the UK is opening up opportunities for science and engineering graduates. He's proud to be working on the project.

"If we're successful, then we'll forever be known as the first people to do it in the UK. So yeah, it is an honour as well as exciting."

While the launch industry is just starting to come together in the UK, it's much better established in other parts of the world.

And one company in particular now dominates the market: Elon Musk's SpaceX.

With their reusable rockets, the company has massively cut the price of sending satellites into space.

SpaceX rockets have been dominating the launch industry

Can the raft of small new rocket companies compete?

Skyrora's CEO Volodymyr Levykin says he wants his rockets to offer a more bespoke service.

"We want to be like a satellite taxi service," he explains.

"To launch whenever the customer wants us to launch and deliver them to an exact position they need to be in orbit."

He thinks because more and more small satellites are being built, the market to launch them will grow - but not every company will make it.

"Some of us, of course, will fail," he says.

"But there are some who are believers in this emerging market. And we decided to invest earlier rather than later, to be ready when the market actually will start to boom."

The UK government says it wants to push the space sector, and is investing in research and development.

The new launch industry will need longer-term help from the government

But UKSpace's Alice Bunn says the support needs to be long term.

"You will not become a global space player by investing in research and development alone. There has to be some kind of government commitment to ongoing operational capability."

She says this could mean the government signing up as a customer for launches, for example.

"We need to think a little bit creatively, industry and government working together, just to get us off the ground here."

All eyes are now on Cornwall, waiting for the first UK launch to blast off.

It will be just the start for this new industry and there will be many challenges ahead.

But as the well-known mantra goes, space is hard - and anyone working in this sector knows this.

The hope is that with this high risk, comes the possibility of sky-high rewards.

Follow Rebecca on Twitter., external

Produced by Alison Francis, senior journalist, Climate and Science

- Published8 November 2022

- Published28 February 2022

- Published13 October 2022