GHGSat: Commercial satellite will see CO2 super-emitters

- Published

Artwork: GHGSat flies the highest-resolution methane sensors in orbit

The world's first commercial satellite dedicated to monitoring carbon dioxide from orbit will launch later this year.

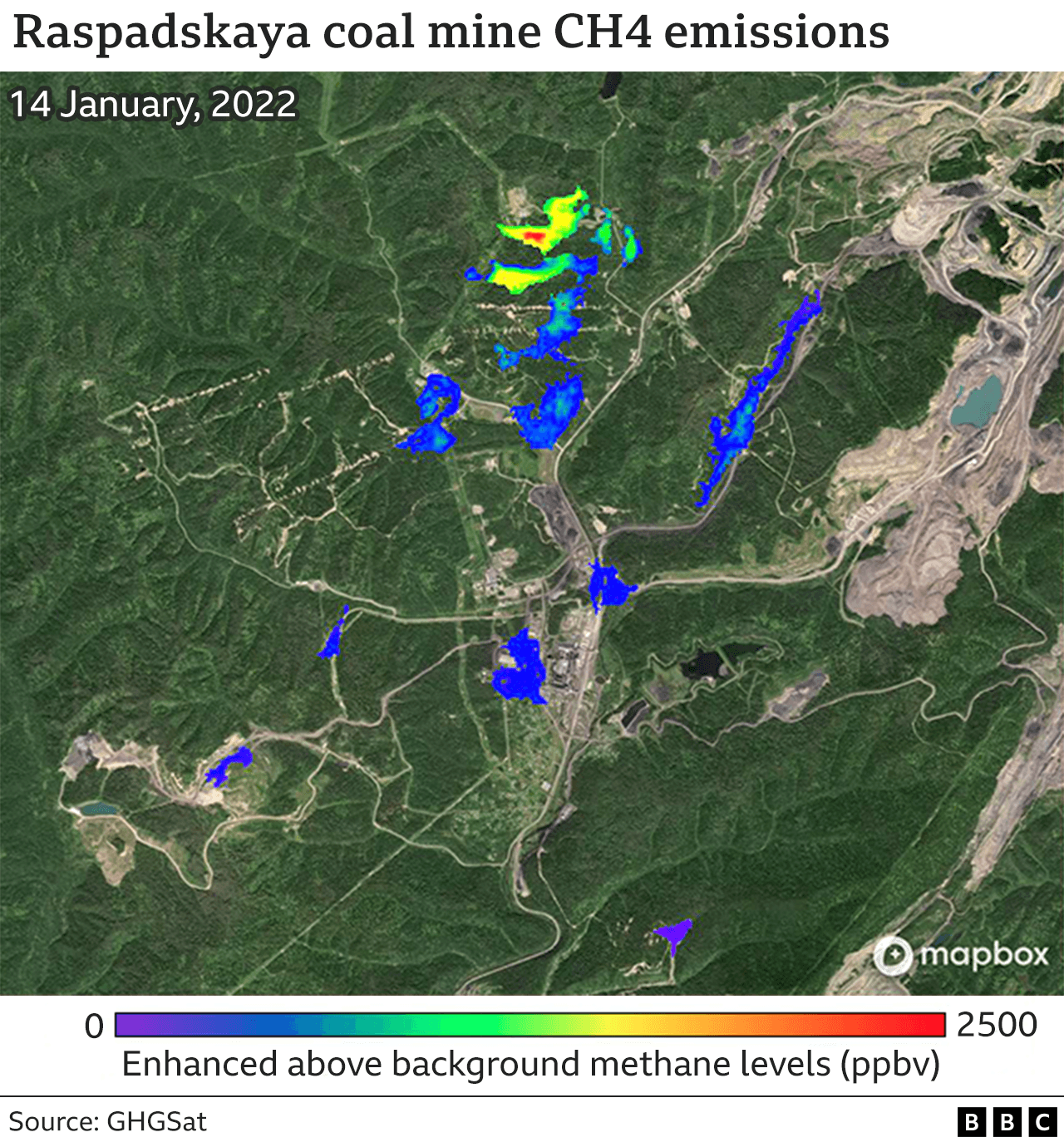

It will be put up by the Canadian company GHGSat, which already flies six spacecraft tracking methane emissions.

The new platform will use the same shortwave infrared sensor but be tuned to CO2's specific light signature in the atmosphere.

The satellite will have a resolution at ground level of 25m, meaning it will be able to see major individual sources.

"We expect to see things like refineries, steel mills, aluminium smelters, cement plants, and, of course, thermal power stations," Stephane Germain, CEO at GHGSat, told BBC News.

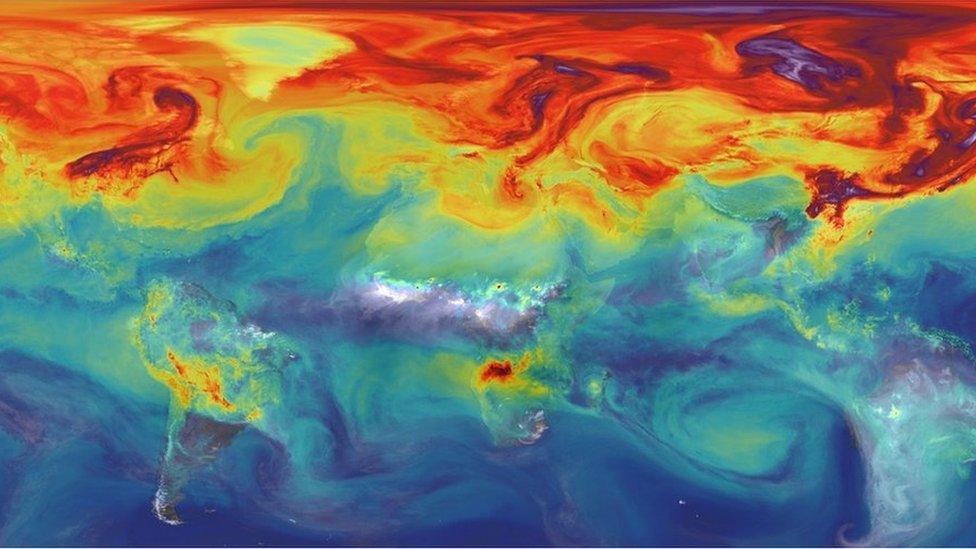

There are already a number national space agency missions tracking CO2. Nasa, for example, flies its Orbiting Carbon Observatories; Japan runs its GoSat mission; and China has TanSat.

But these generally make large area maps of variations in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere; they're not really set up to hone in on super-emitters at the scale of an individual industrial complex.

Higher concentrations (red) of CO2 in the atmosphere are already mapped by satellite on a broad scale

To monitor CO2, the GHGSat sensor will have to work at a higher detection threshold than for Methane.

CH4 is a much smaller component of the air - about 1.9 molecules in every million, versus 418 for carbon dioxide - making it much easier to see a methane spike above the normal background.

GHGSat-C10, as the new satellite will be known, will target a detection threshold of one megatonne per year.

"It's not as if we have to find the big CO2 emitters; we already know where they are," said Dr Germain. "Unlike methane, which is fugitive - it shows up in places and at times you don't necessarily expect - we know where the large power plants are in the world; we know where the aluminium smelters are. So, this is more about being able to verify emissions."

GHGSat expects to sell its data to governments and financial services markets. The information will be used to check emissions estimates.

Modern plants will likely have deployed continuous emissions monitoring systems, perhaps in flue gas stacks. But even these operations may want occasional independent observations.

And under the Paris Climate Accord, countries must compile CO2 inventories. The GHGSat data could help with international comparisons.

"We'll see how we get on but we do have the aspiration of launching several more carbon dioxide satellites," Dr Germain said.

"Ultimately, we'd like to get to at least monthly coverage of every major CO2 source in the world, and potentially even a weekly coverage of every source in the world."

GHGSat has built its business on monitoring methane at the scale of an individual industrial facility