What is gene-edited food and is it safe to eat?

- Published

Produce like these gene-edited tomatoes with added vitamin D could be sold commercially in England

The law has changed to allow gene-edited food to be developed and sold in England.

The government hopes the technology will boost jobs and improve food production, but safety and environmental worries mean it is not allowed in other parts of the UK.

What is gene-edited food?

For many years, farmers produced new varieties through traditional cross-breeding techniques.

They might, for instance, combine a big but not very tasty cabbage with a small but delicious one to create the perfect vegetable.

But this process can take years, because getting the hundreds of thousands of genes in cabbages to mix in just the right way to produce large but tasty offspring is a matter of trial and error.

Genetic methods remove the random element.

They let scientists identify which genes determine size and flavour, and insert them in the right places to develop the new variety much more quickly.

Which genetic techniques are used?

Genetic modification (GM), which has been common in most parts of the world for more than 20 years, though not in the European Union (EU).

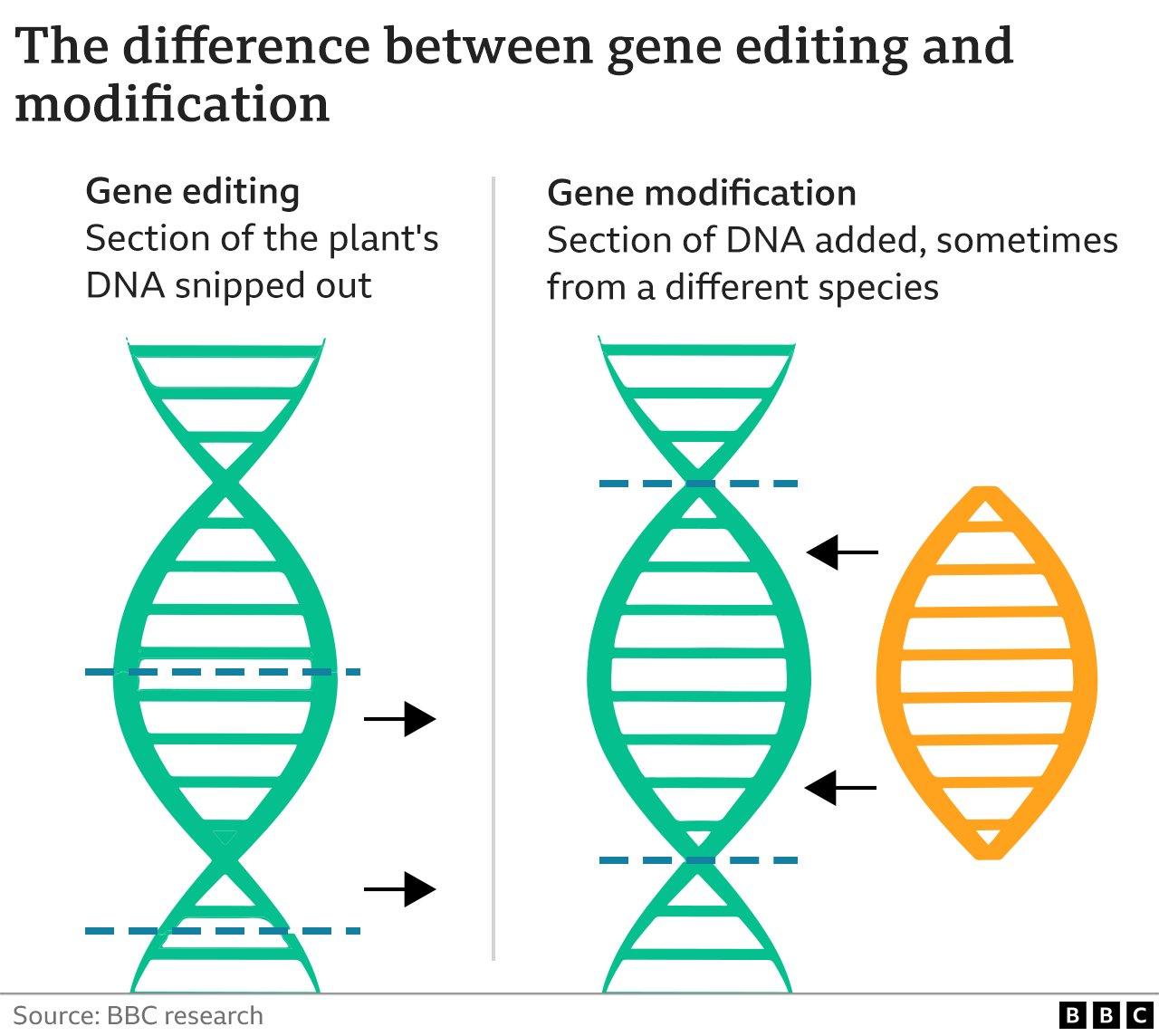

GM involves adding genes to a plant's DNA from a different species of plant - or even an animal. It creates new varieties which could not have been produced through cross-breeding.

Cisgenesis, which is like GM, but involves adding genes from the same or very closely-related species, which the new rules will allow if the resulting crop is something that could have been produced through traditional cross breeding.

Gene-editing (GE), which is a much newer technique that lets scientists target specific genes. The new law lets plant breeders switch them on or off by removing a small section of DNA - again, provided the resulting crop could have been naturally produced.

When will gene-edited foods be available in the UK?

Brexit let the government introduce much lighter regulations for gene-edited crops in England than are in place across the EU.

But you will not see GE produce in shops straight away.

The technology is still relatively new, and it may take several years before new varieties are on sale. But they are on the way.

The legislation also opens the door to the sale of meat, eggs and dairy from gene-edited animals.

But MPs would have to approve this separately, because the government is still considering the potential impact on animal welfare. There is no clear timetable for when this might happen.

Gene-edited pigs immune to lung disease were produced in Scotland

The new rules do not require GE foods to be labelled as such, because Westminster considers them no different to conventional produce.

So far, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have not changed their laws on GE crops.

What gene-edited food will I be able to buy?

In Japan, you can already buy tomatoes rich in a chemical called GABA, which has a calming effect, and modified sea bream where more of the flesh is suitable for sushi.

A US firm is developing seedless blackberries and stoneless cherries.

In the UK, researchers have developed tomatoes that contain vitamin D. Scientists in Hertfordshire have also been experimenting with gene-edited wheat.

Wheat in Hertfordshire has been gene-edited to help boost crop yields

However, the food industry mainly wants to use GE technology to speed up the development of new varieties of current crops.

Firms also want to be able to tailor crops more precisely: producing starchier potatoes for crisp-makers, or protein-rich veg to use as a meat substitute.

Companies are also keen to introduce traits that improve yields, and to create varieties that are more resilient to climate change.

Are gene-edited foods safe?

Scientists insist that each of the three genetic techniques produces food that is safe to eat, and point out that all food is rigorously tested.

They argue that GM crops have been consumed by billions of consumers in North and South America and Asia for more than 25 years with no ill-effects.

However, concerns over health risks and the environmental impact have meant that neither GM nor GE crops can be commercially produced or sold in the EU, although there are some signs that this may change.

What are the safety concerns?

Many campaigners who are opposed to gene-edited foods make no distinction between these and those produced by the earlier GM technology.

They are worried that GE foods will not require additional testing, and fear the creation of new allergens or toxins.

They are also concerned about the impact GE crops could have on the environment.

However, scientists say that there is no evidence that GM crops have harmed human health or damaged ecosystems, and they expect the same to be true for GE crops.

The Westminster government believes that because gene-edited produce is indistinguishable from natural varieties, they will face less opposition than their GM equivalents.

Recent unpublished polling by YouGov for the Department for Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) backs this view, but a large minority remains opposed:

54% said GE crops were "acceptable"

28% said they were "unacceptable"

The polling also found that 78% were in favour of some environmentally-beneficial applications of GE, such as the reduced use of pesticides and herbicides.

But there was less support for the use of gene-editing in animals, over fears the technology might cause suffering.

- Published12 November 2021