European Space Agency: Blast off for Jupiter icy moons mission

- Published

Europe's mission to the icy moons of Jupiter has blasted away from Earth.

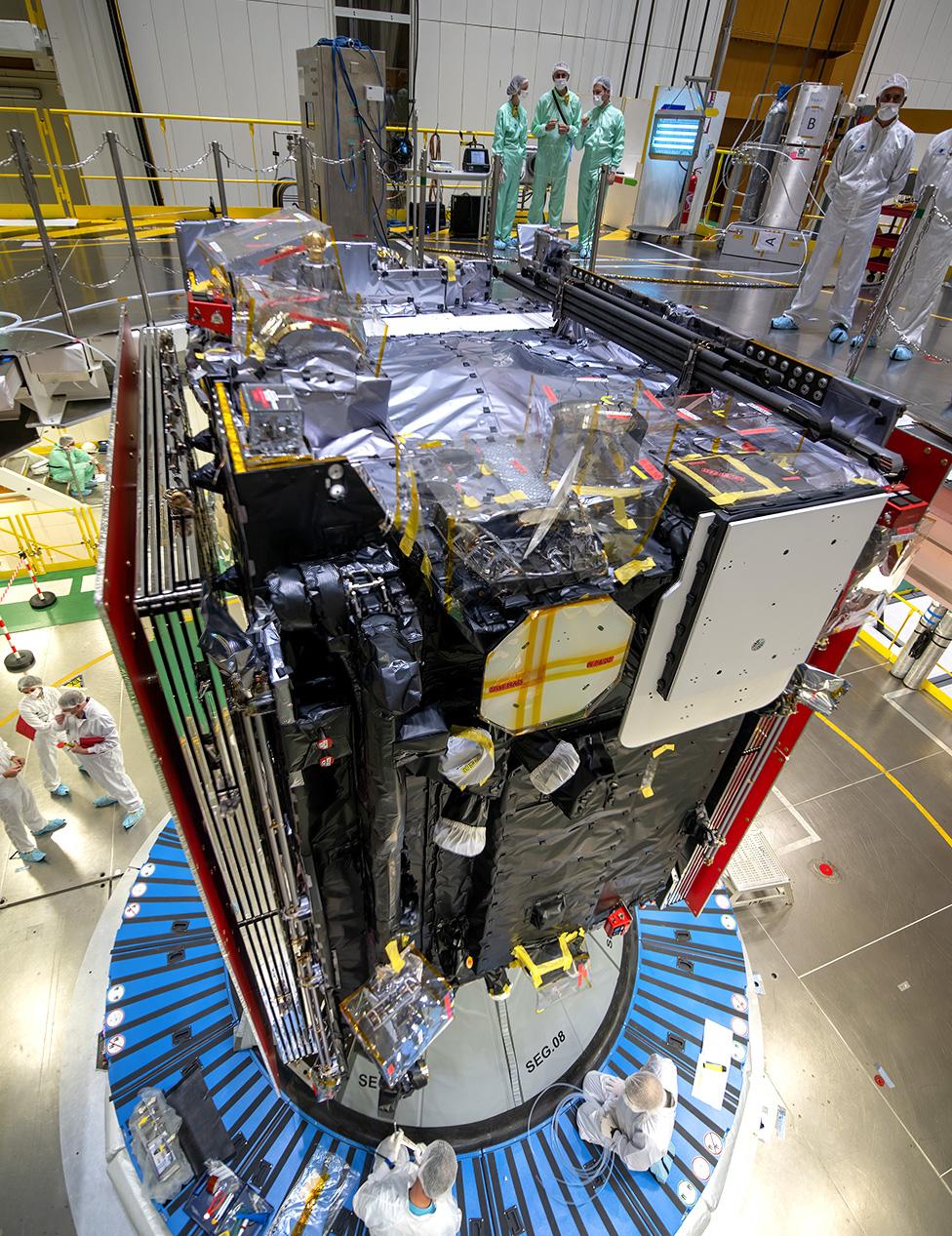

The Juice satellite was sent skyward on an Ariane-5 rocket from the Kourou spaceport in French Guiana.

There was joy, relief and lots of hugs when the watching scientists, officials and VIPs were told the flight to orbit had been successful.

It is second time lucky for the European Space Agency (Esa) project after Thursday's launch attempt had to be stood down because of the weather.

Juice called home shortly after coming off the top of the Ariane. A key milestone was confirmation that the satellite's enormous solar array system had also deployed correctly - all 90 sq m (98 sq yds) of it.

"We have a mission; we're flying to Jupiter; we go fully loaded with questions. Juice is coming, Jupiter! Get ready for it," announced Andrea Accomazzo, the operations director at Esa's mission control in Darmstad, Germany.

The agency's director general, Dr Josef Aschbacher, also expressed his pride that the €1.6bn (£1.4bn; $1.7bn) mission was safely on its way.

"But I do have to remind everyone, there's still a long way to go," he said. "We have to test all the instruments to make sure they function as expected, and then, of course, arrive at Jupiter. But we have taken a very big step towards our goal."

The Juice spacecraft carries 10 instruments to study Jupiter's moons

The Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) is being sent to the largest planet in the Solar System to study its major moons - Callisto, Ganymede and Europa.

These worlds are thought to retain vast reservoirs of liquid water.

Scientists are intrigued to know whether the moons might also host life.

This might sound fanciful. Jupiter is in the cold, outer reaches of the Solar System, far from the Sun and receiving just one twenty-fifth of the light falling on Earth.

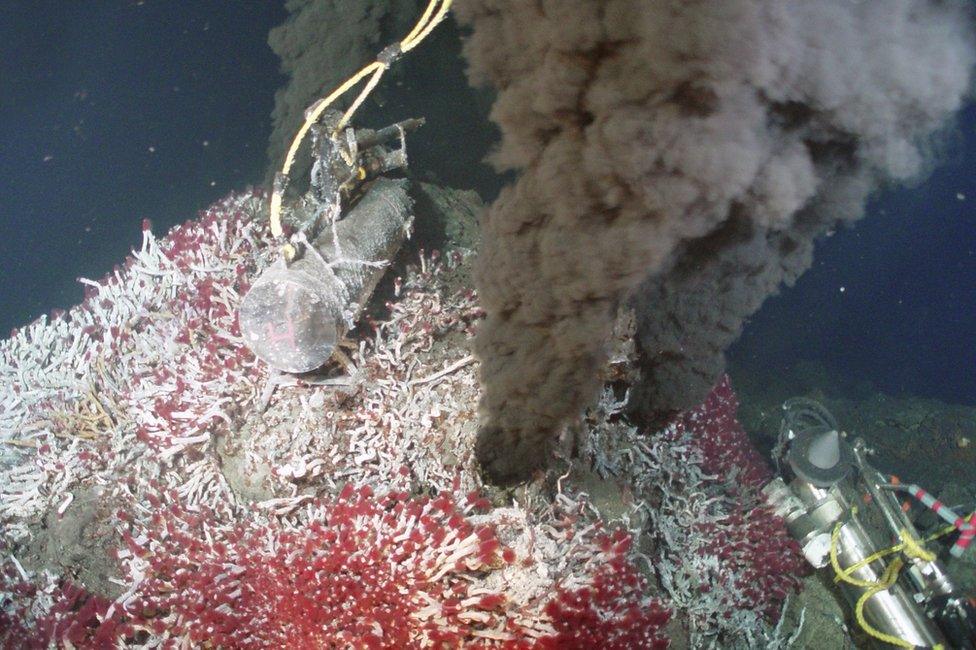

But the gravitational squeezing the gas giant exerts on its moons means they potentially have the energy and warmth to drive simple ecosystems - much like the ones that exist around volcanic vents on Earth's ocean floors.

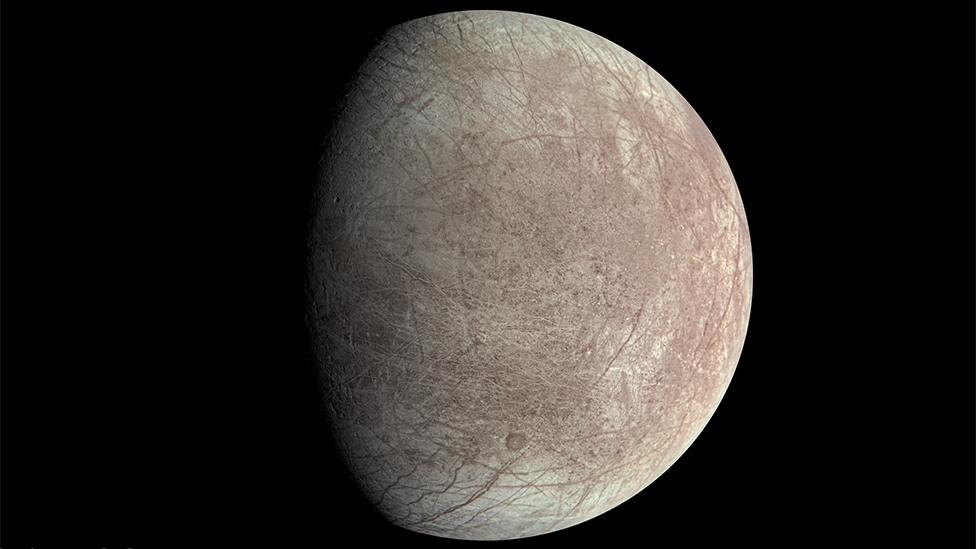

"In the case of Europa, it's thought there's a deep ocean, maybe 100km (62 miles) deep, underneath its ice crust," said mission scientist Prof Emma Bunce from Leicester University, UK.

"That depth of ocean is 10 times that of the deepest ocean on Earth, and the ocean is in contact, we think, with a rocky floor. So that provides a scenario where there is mixing and some interesting chemistry," the researcher told BBC News.

Ariane doesn't have the heft to send Juice direct to its destination, at least not in a useful timeframe.

Instead, the rocket has despatched the spacecraft on to a path around the inner Solar System. A series of fly-bys of Venus and Earth will then gravitationally sling the mission out to its intended destination.

It's a 6.6 billion km journey lasting 8.5 years. Arrival in the Jovian system is expected in July 2031.

The ice-covered Callisto, Ganymede and Europa were discovered by the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei in 1610, using the recently invented telescope. He could see them as little dots turning about Jupiter. (He could also see a fourth body we now know as Io, a world covered in volcanoes).

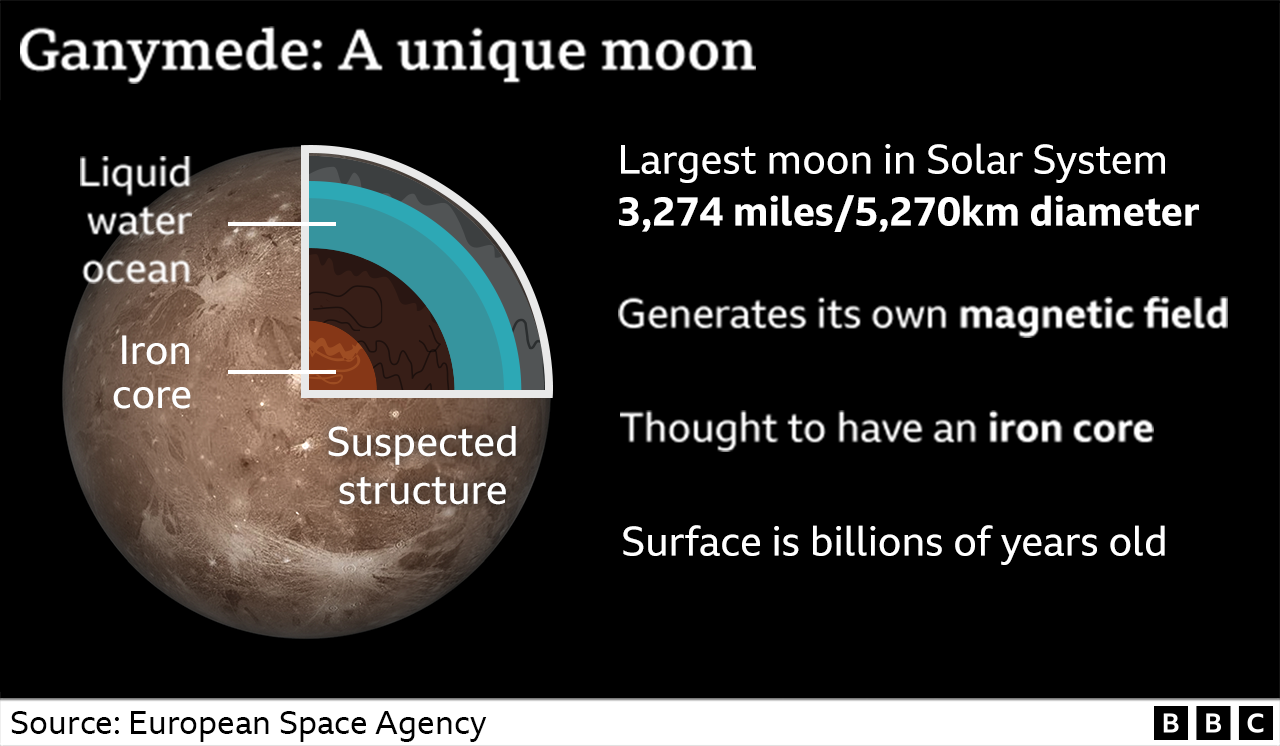

The icy trio range in diameter from 3,100km to 5,300km. To put this in context, Earth's natural satellite is roughly 3,500km across.

Prof Emma Bunce: "The first spacecraft to go into orbit around an outer Solar System moon"

Juice will study the moons remotely. That's to say, it will fly over their surfaces; it won't land. Ganymede - the largest moon in the Solar System - is the satellite's ultimate target. It will end its tour by going into orbit around this world in 2034.

Radar will be used to see into the moons; lidar, a laser measurement device, will be used to create 3D maps of their surfaces; magnetometers will explore their intricate electrical and magnetic environments; and other sensors will collect data on the whirling particles that surround the moons. Cameras, of course, will send back countless pictures.

Volcanic vents on Earth's ocean floor are a model for what could exist on these moons

All this will be occurring several hundred million km from Earth where the light conditions will be dim, to say the least.

The satellite will need all the power it can get from its huge solar wings. Even at their scale, they'll still only be producing just about enough "juice" to run the equivalent of a domestic microwave oven - approximately 850 watts.

Carole Mundell: "Liquid water we think is a precondition for habitability"

The mission won't be looking for particular "biomarkers" or attempting to locate alien fish.

The objective is to gather more information regarding potential habitability so that subsequent missions can address the life question more directly.

Already scientists are thinking about how they could put landers on one of Jupiter's frozen moons to drill through its crust to the water beneath.

In Earth's Antarctica, researchers use heat to bore hundreds of metres through the ice sheet to deploy submersibles in places where the local ocean is frozen over.

It's challenging work and would be an even greater task on a Jovian moon where the ice crust might be tens of kilometres thick.

Robots that dive beneath the ice of Antarctica are already in use

Juice won't be alone in its work.

The US space agency Nasa is sending its own satellite called Clipper.

Although it will leave Earth after Juice, next year, it should arrive just before its European sibling. It has the benefit of a more powerful launch rocket.

Clipper will focus its investigations on Europa, but will do much the same work.

"There is great complementarity and the teams are very keen to collaborate," said Prof Carole Mundell, the director of science at the European Space Agency.

"Certainly, there's going to be a wealth of data. But, first, we've got to make sure our missions get to Jupiter and are operating safely," she told BBC News.

The American Clipper mission should launch in 2024 and focus on Europa