UK 'knitted satellite' will see Earth day or night

- Published

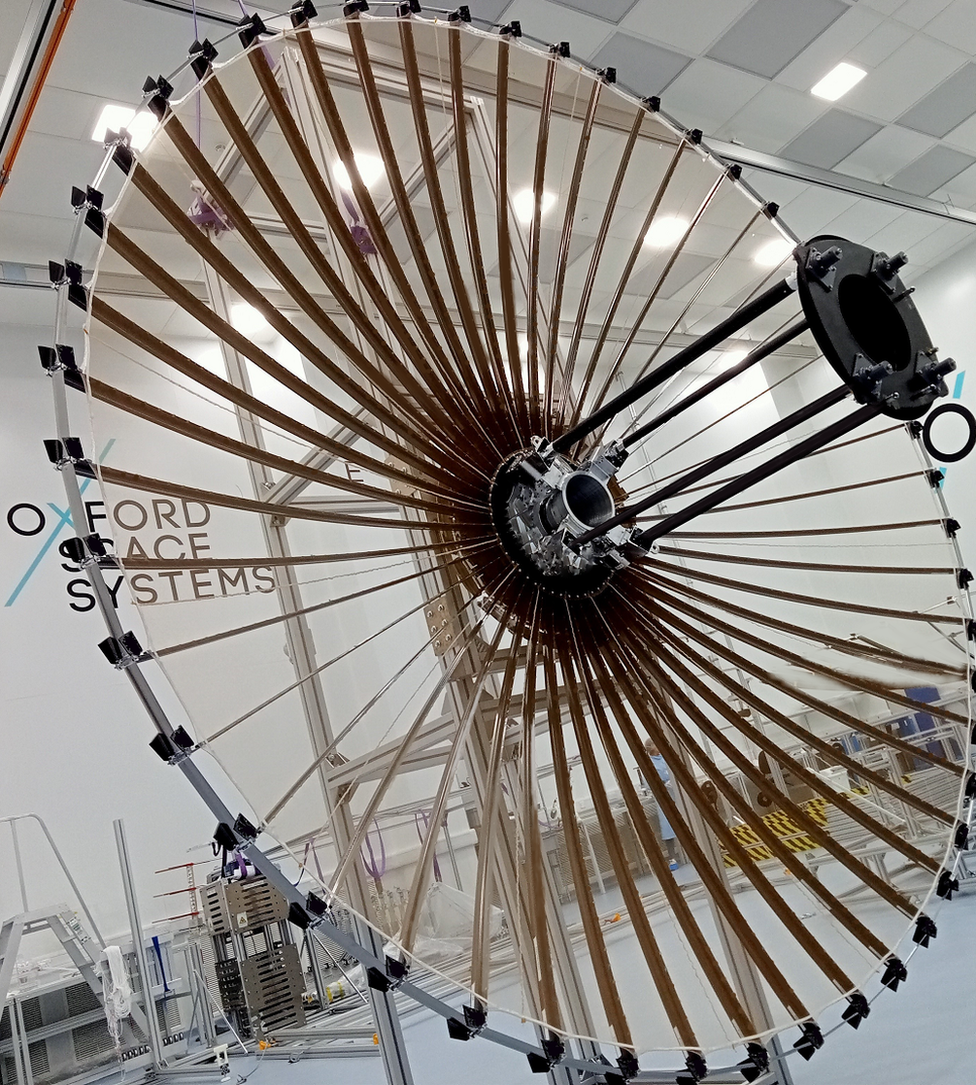

The antenna opens up a bit like an umbrella

Two British companies are to fly an innovative, low-cost radar satellite - part of which will be knitted on a knitting machine.

Called CarbSar, the mission will launch next year, and could help fill a gap in Britain's spying capacity.

The satellite will use radar technology to see through cloud and will even work at night.

The Ukraine conflict has shown the value of such systems, which have been used to monitor Russian positions.

But Britain is the only permanent member of the UN Security Council without its own system.

The two UK companies - Surrey Satellite Technology Limited and Oxford Space Systems - believe they can provide a similar, home-grown capability.

They will start building their spacecraft this year - with government support - and with a launch on an American rocket already booked.

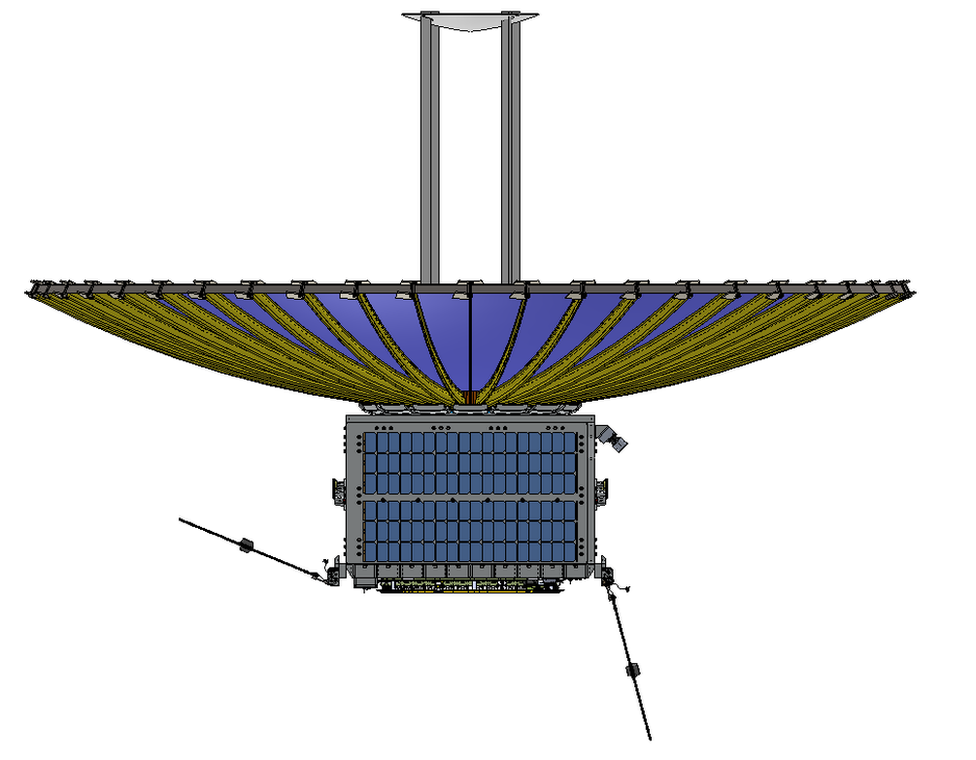

WATCH: This OSS video illustrates how the antenna would deploy in space

SSTL has a long-established reputation for aerospace manufacturing; the real novelty is in the OSS radar antenna.

It features a knitted tungsten wire mesh that's folded tightly for launch but which will spring out once in orbit to form a large umbrella-like shape.

It's through this 3m-wide antenna/reflector that the satellite will image the ground.

SSTL and OSS hope their CarbSar pathfinder will put them in a strong position to win future contracts to supply operational spacecraft to the UK government for both civil and military applications.

The government is keen to see what the knitted satellites can achieve. Part of the funding has come from the National Security Strategic Investment Fund, which backs promising technologies that might be used for national security and defence.

The satellite concept has received government defence R&D support

SSTL will build the bulk of CarbSar, including all the internal systems that drive the satellite, and the electronics that make the radar work.

OSS will provide its deployable antenna/reflector, a prototype of which is already going through testing at the company's Harwell headquarters.

The firm calls the structure a "wrapped rib" design.

The gold-plated tungsten mesh is attached to a series of carbon-composite rods that can be wound radially against a central hub.

The idea is that once released, the strain energy in these rods, or ribs, will naturally want to jump back into their straightened configuration, pulling the mesh into position in the process.

Think of the builder's tape measure and how it always wants to snap longways when unrolled.

The mesh has to be made to exacting standards to deliver the wanted performance

OSS has a big rig at its factory where it practices stowing and deploying the antenna, time and time again.

"You need it to be as simple as possible because the more parts you have the more chance there is for something to go wrong," explains company CEO Sean Sutcliffe.

"It's also got to work every time, so you need to make sure it has enough strain energy to know that it's definitely going to come out fully - that it won't stall half way through. But then you also don't want the system to have so much energy that it tears itself apart or damages the satellite," he told BBC News.

The mesh itself is remarkable - as is the process of manufacturing it.

The yarn is almost invisible. Reels of it feed the industrial knitting machine in the factory which is operated by a former fashion lecturer from Denmark.

Knitting machine: Not something you expect to see in a satellite factory

Precision is everything. When the mesh is pulled tight it must conform to exacting standards.

"We've got a laser scanner and we scan the mesh before stowing and after deployment to check it hasn't deviated from the parabolic shape. We're seeking less than a millimetre's deviation," said OSS business development director Michael Lawrence.

The UK has talked for some years about having a network of radar satellites.

The Ministry of Defence has been promised money to procure them.

But the sensing technology is very useful also in civil emergency situations, such as monitoring the extent of flooding or finding evidence of landslips and subsidence.

Radar guarantees an image every time the satellite passes overhead because its vision is unobstructed by whatever the weather might be doing at the time.

SSTL launched a radar satellite of its own in 2018 but it is hoping the CarbSar model will have added appeal. For one thing, it should have much higher resolution, seeing objects less than a metre across.