Peruvian fossil challenges blue whales for size

- Published

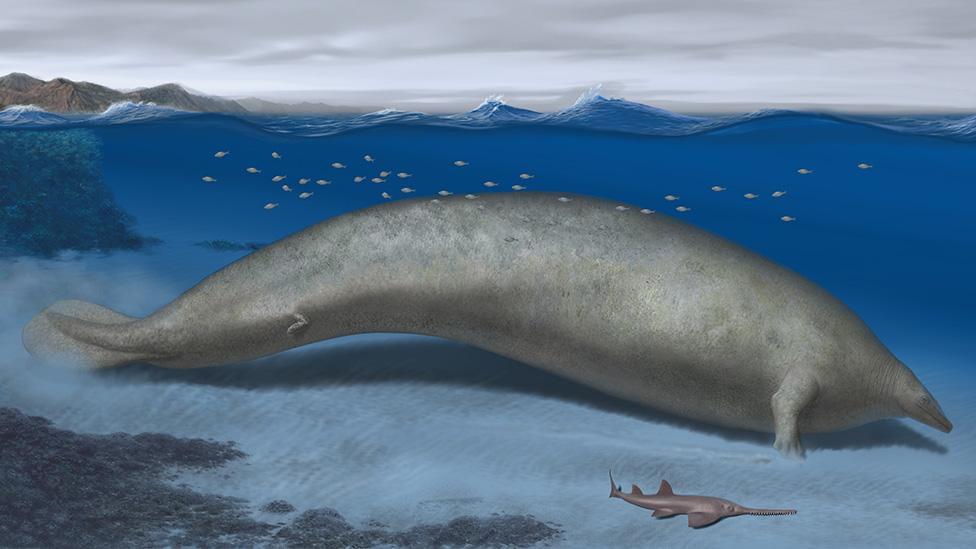

With its dense, heavy bones, Perucetus could only have foraged in shallow waters

Scientists have identified a new candidate for the heaviest ever animal on Planet Earth.

It's an ancient, long-extinct whale that would have tipped the scales at close to 200 tonnes.

Only some of the very biggest blue whale specimens might have rivalled its heft, researchers say.

The creature's fossilised bones were dug up in the desert in southern Peru, so it has been given the name Perucetus colossus.

Dating of the sediments around the remains suggests it lived about 39 million years ago.

"The fossils were actually discovered 13 years ago, but their size and shape meant it took three years just to get them to Lima (the capital of Peru), where they've been studied ever since," said Dr Eli Amson, a co-worker on the discovery team led by palaeontologist Dr Mario Urbina.

It took an immense effort to extricate the bones from the hard desert rock

Eighteen bones were recovered from the marine mammal - an early type of whale known as a basilosaurid. These included 13 vertebrae, four ribs and part of a hip bone.

But even given these fragmentary elements and their age, scientists were still able to decipher a huge amount about the creature.

In particular, it's evident the bones were extremely dense, caused by a process known as osteosclerosis, in which inner cavities are filled. The bones were also oversized, in the sense they had extra growth on their exterior surfaces - something called pachyostosis.

These weren't features of disease, the team said, but rather adaptations that would have given this large whale the necessary buoyancy control when foraging in shallow waters. Similar bone features are seen for example in modern-day manatees, or sea cows, which also inhabit coastal zones in certain parts of the world.

Perucetus would have been shorter than the average blue whale but much heavier

"Each vertebra weighs over 100kg, which is just completely mind-blowing," said co-worker Dr Rebecca Bennion from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels.

"It took several men to shift them out into the middle of the floor in the museum for me to do some 3D scanning. The team that drilled into the centre of some of these vertebrae to work out the bone density - the bone was so dense, it broke the drill on the first attempt."

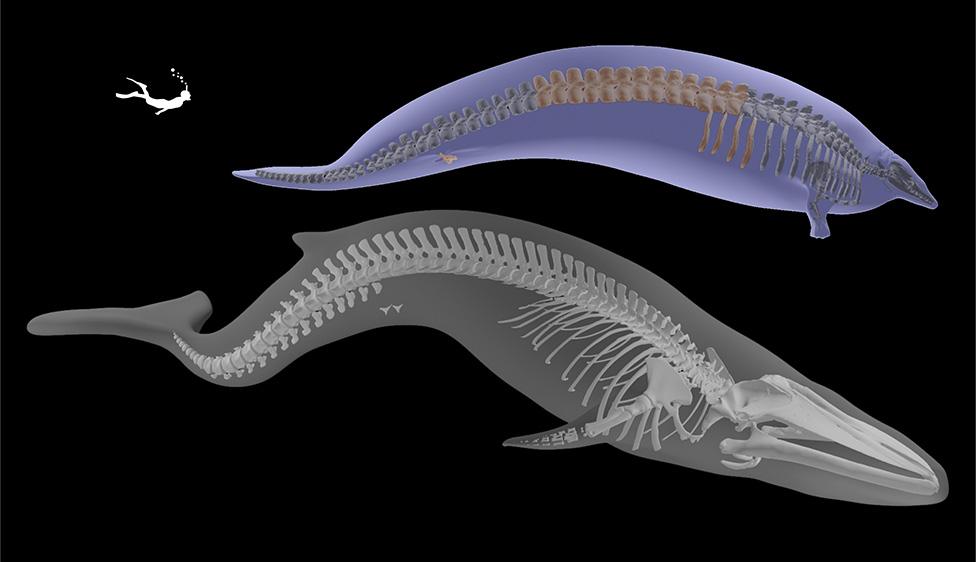

When confronted with a skeleton of a long-extinct species, scientists use models to try to reconstruct the body shape and mass of the animal. They do this based on what they know about the biology of comparable living creatures.

It is predicted Perucetus would have been about 17-20m in length, which is not exceptional. But its bone mass alone would have been somewhere between 5.3 and 7.6 tonnes. And by the time you add in organs, muscle and blubber, it could have weighed - depending on the assumptions - anywhere between 85 tonnes and 320 tonnes.

The bones are going on display in Lima to celebrate their description in a scientific journal

Dr Amson, a curator at Germany's State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, uses a median number of 180.

The largest blue whales recorded during the era of commercial exploitation were at this scale.

"What we like to say is that Perucetus is in the same ball park as the blue whale," he told BBC News.

"But there's no reason to think that our individual was particularly big or small; it was likely just part of the general population. So it's worth keeping in mind that when we use the median estimate, it's already at the very upper ranges of what blue whales can measure."

The largest dinosaurs might have been about 100 tonnes in weight

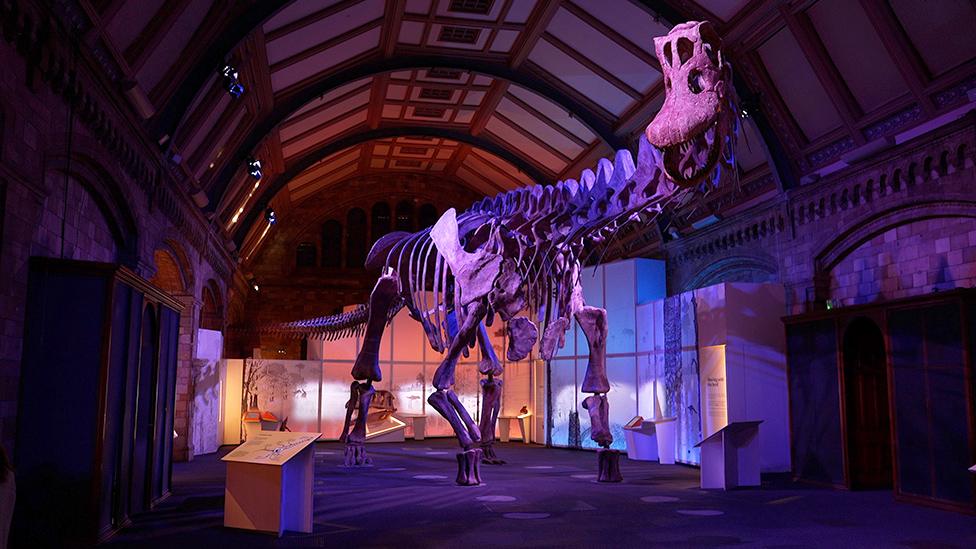

One of the comparators used by the research team in its investigations is a blue whale that will be very familiar to anyone who has visited the Natural History Museum in London.

Nicknamed Hope, this animal's skeleton took pride of place at the institution when it was hung from the ceiling in the main hall in 2017.

But before being installed, the skeleton was scanned and described in great detail and is now an important data resource for scientists across the world.

Hope: The London whale skeleton is a key resource for scientists worldwide

In life, Perucetus' skeletal mass would have been two to three times that of Hope, even though the London mammal was a good five metres longer.

Richard Sabin, the curator of marine mammals at the NHM, is thrilled by the new find and would love to bring some aspect of it to London for display.

"We took the time to digitise Hope - to measure not just the weight of the bones but their shape as well, and our whale has now become something of a touchstone for people," he said.

"We don't get hung up on labels - like 'which was the largest specimen?' - because we know science at some point will always come along with new data.

"What's amazing about Perucetus is that it demonstrated so much mass some 30 million-plus years ago when we thought gigantism occurred in whales only 4.5 million years ago."

Perucetus colossus is reported in the journal Nature, external.

The very biggest blue whales could reach near 200 tonnes, but that was before commercial whaling