Elon Musk's Starship rocket goes further and higher - but is then lost

- Published

Watch: SpaceX's Starship goes further and higher on its second test flight

US company SpaceX says it has made significant progress in the development of its mammoth new rocket, Starship, after a second test flight from Texas.

The 120m-tall (395ft) vehicle made an explosive debut in April, but went further and higher on its latest outing.

The rocket's flight was again cut short because of technical issues, but it was clear previous problems had been fixed.

The company was congratulated on its efforts by the American space agency.

Nasa chief Bill Nelson tweeted: "Spaceflight is a bold adventure demanding a can-do spirit and daring innovation. Today's test is an opportunity to learn - then fly again."

The agency wants to use a version of Starship to land humans on the Moon later this decade.

The two-part Starship vehicle left its launch complex at Boca Chica on the Texan coast just after 07:00 local time (13:00 GMT) on what was planned to be a 90-minute mission.

The goal was to get the top segment - a 50m-tall (165ft) uncrewed stage called simply "the Ship" - to make one near-complete revolution of the Earth, ending in a splashdown near Hawaii.

It didn't make it that far: Onboard computers terminated the mission with explosive charges about eight minutes after lift-off, for a reason that's not yet clear.

But the mere fact that the flight lasted that long will be regarded as a big step forward by SpaceX and its CEO, the entrepreneur Elon Musk.

The early phases of flight experienced none of the drama seen in April's test

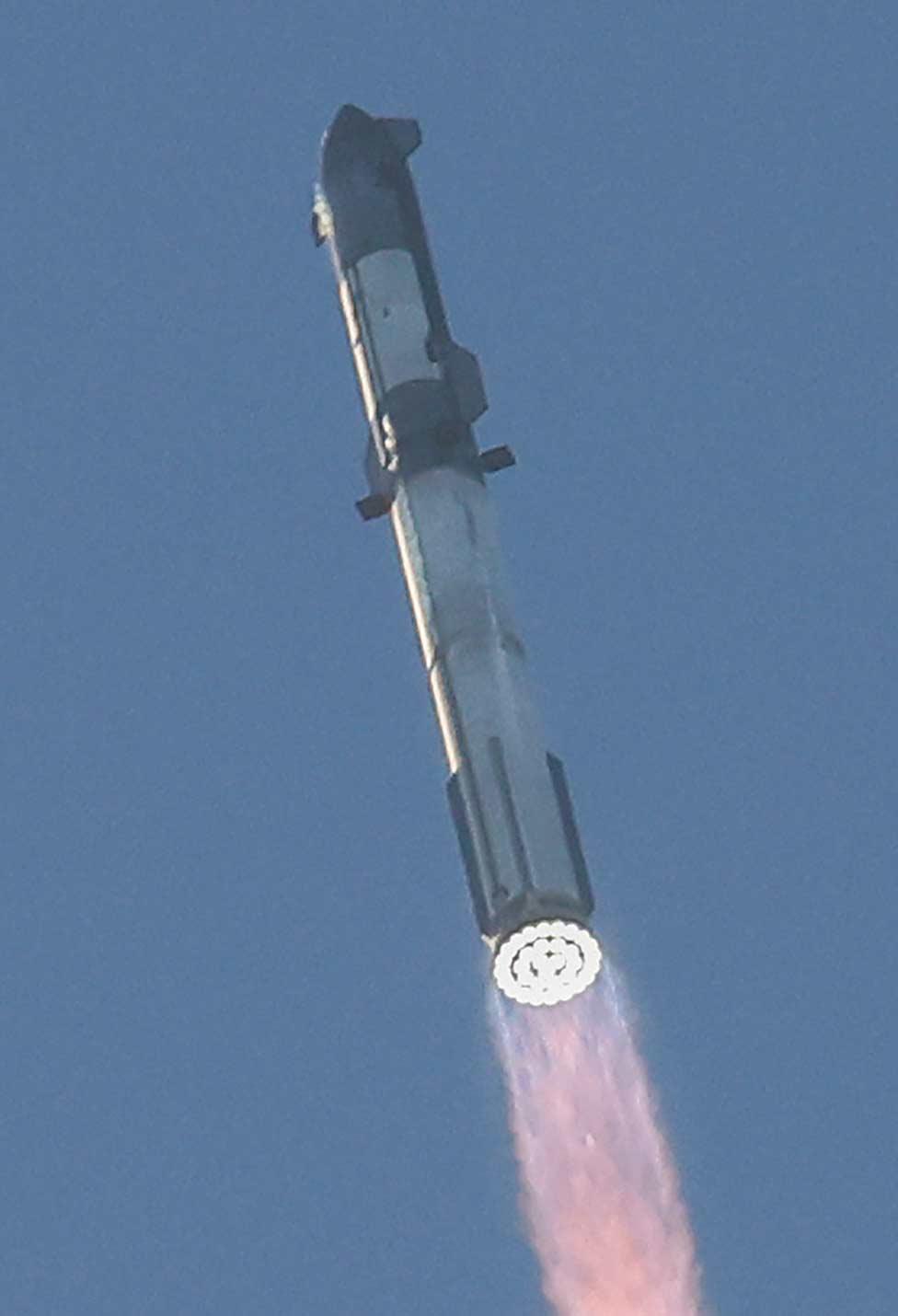

Back in April, Starship damaged its launchpad as it left the ground, suffered numerous engine failures on its lower-stage - the Super Heavy booster - and failed to separate the Ship at altitude as designed. Saturday's test got through all of those initial phases without drama.

Engineers will though want to know why the booster tore itself apart shortly after stage separation and get to the root cause for the Ship's loss when it reached nearly 150km (90 miles) above the planet.

"It's such an incredibly successful day, even though we did have a 'rapid unscheduled disassembly' of both the Super Heavy booster and the Ship," observed SpaceX webcast commentator Kate Tice. "That's great. We got so much data and that will all help us to improve for our next flight."

Large crowds had gathered on the Texas coast to watch the launch

One might expect SpaceX to be pleased, but outside experts were also impressed with the improvements that had been made.

"This time all the 33 engines, which are called Raptor engines, were all up and running during lift-off. And this allowed Starship to actually reach what we call first-stage separation which is the most interesting part - this is what they wanted to test," said Dr Emma Gatti, editor in chief of Space Watch Global.

Dr Phil Metzger is a former Nasa scientist, now with the University of Central Florida, who studies rocket systems. He told BBC News: "Elon was predicting a 60% chance of success. And I would say that they probably got 60% success.

"They'll be looking at the data. A rocket has a huge amount of data being sent to the ground. They'll have data on every system and subsystem imaginable, so I don't doubt they're going to be able to pinpoint the causes of what did go wrong; and I'm sure they'll be pressing ahead for their next launch as soon as possible."

The booster did its primary job of getting the system off the ground, but then exploded

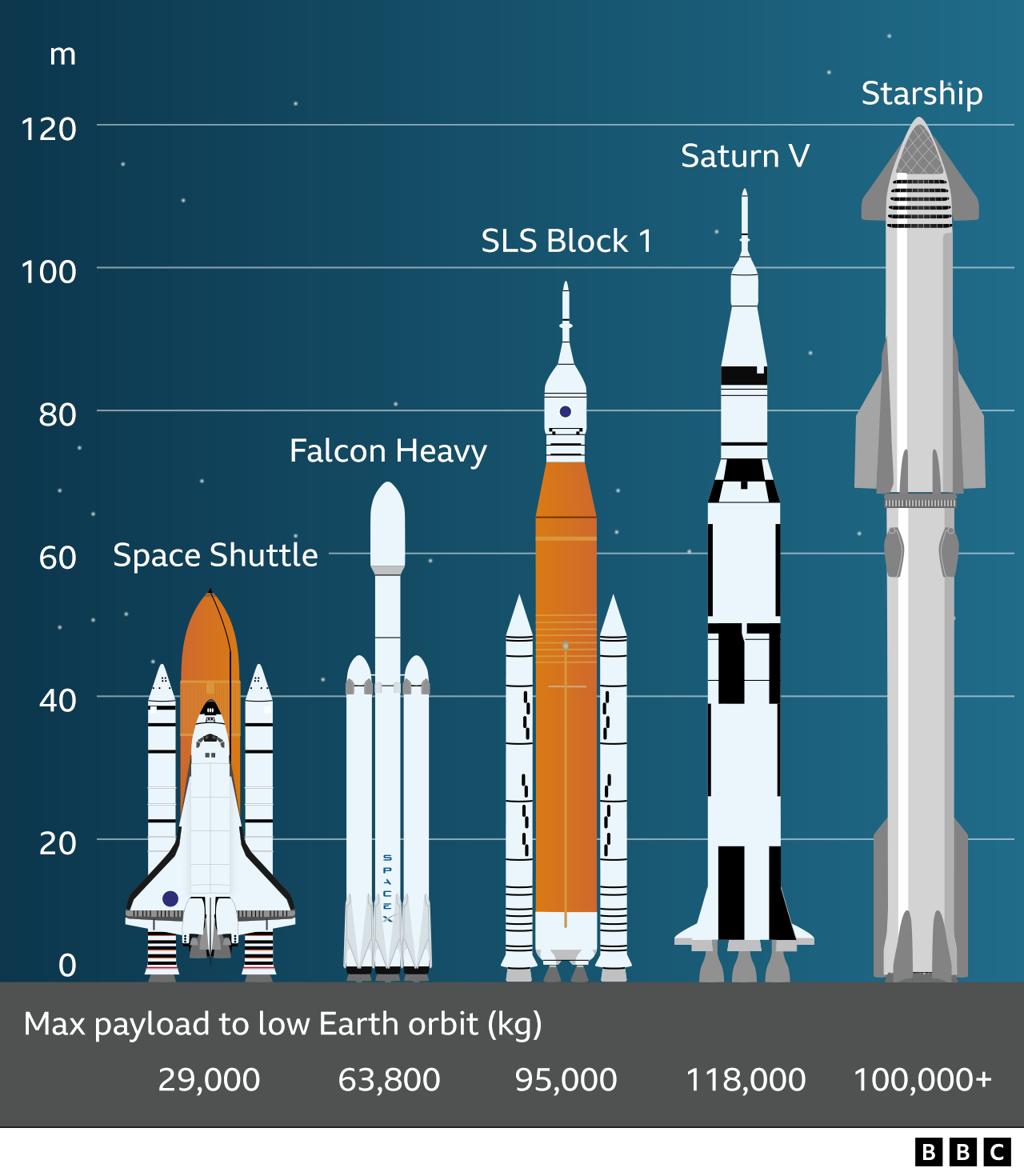

Starship is the most powerful rocket system ever to lift off Earth.

The 33 engines at the base of the Super Heavy booster produce 74 meganewtons of thrust. This dwarfs all previous vehicles, including those that sent men to the Moon in the 1960s/70s.

If SpaceX engineers can perfect Starship, it will be revolutionary.

It's intended to be fully and rapidly reusable, to operate much like an aeroplane that can be refuelled and put back in the air in quick order.

This capability, along with the heft to carry more than a hundred tonnes to orbit in one go, would radically lower the cost of space activity.

For Elon Musk, Starship is key to realising his long-held ambition of taking people and supplies to Mars to build a human settlement. It will also assist his Starlink project which is establishing a global network of broadband internet satellites.

There are thousands of Starlink spacecraft in orbit already, but later models will be larger and heavier and Starship will be needed to get them to space.

- Published18 November 2023