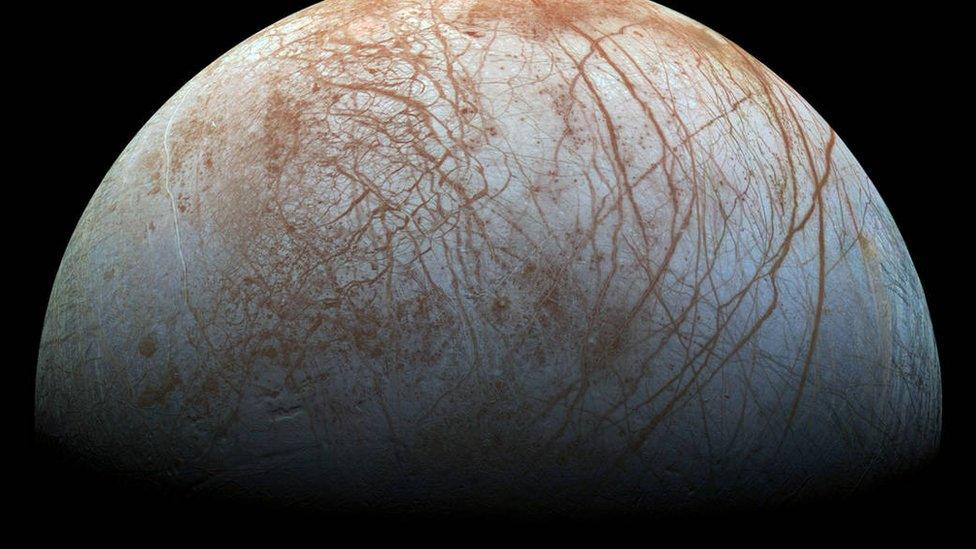

'Perfect solar system' found in search for alien life

- Published

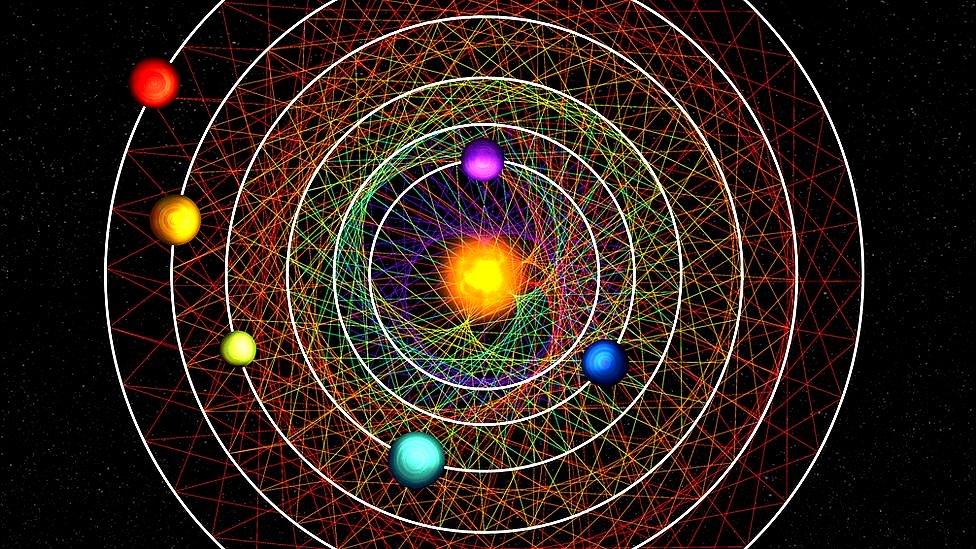

Artwork: Six worlds around a star like our Sun are ideal to study how planets formed and whether they are home to life

Researchers have located "the perfect solar system", forged without the violent collisions that made our own a hotchpotch of different-sized planets.

The system, 100 light years away, has six planets, all about the same size. They've barely changed since its formation up to 12 billion years ago.

These undisturbed conditions make it ideal for learning how these worlds formed and whether they host life.

The research has been published in the scientific journal, Nature.

The creation of our own solar system was a violent process. As planets were forming some crashed into each other, disturbing orbits and leaving us with giants like Jupiter and Saturn alongside relatively small worlds like our own.

In the system HD110067, as astronomers have rather drily named it, things couldn't be more different.

Artwork: Planet formation is typically a violent process

Not only are the planets similarly sized; in a far cry from the unrelated timing of the orbits of the planets in our own solar system, these rotate in synch.

In the time it takes for the innermost planet to go around the star three times, the next planet along gets around twice, and so on out to the fourth planet in the system. From there things change to a 4:3 pattern of relative orbit speeds for the last two planets.

This intricate planetary choreography is so precise that that the researchers have created a cyclical musical piece, akin to a Philip Glass-style composition, with notes and rhythms corresponding to each planet and their orbital periods. You can listen to some of it here:

A musical take on the 'perfect solar system'

Dr Rafael Luque, of the University of Chicago, who led the research described HD110067 as "the perfect solar system".

"It is ideal for studying how planets are created, because this solar system didn't have the chaotic beginnings ours did and has been undisturbed since its formation."

Dr Marina Lafarga-Magro, of Warwick University, said that the system was "beautiful and unique".

"It is really exciting, just seeing something that no-one has seen before," she told BBC News.

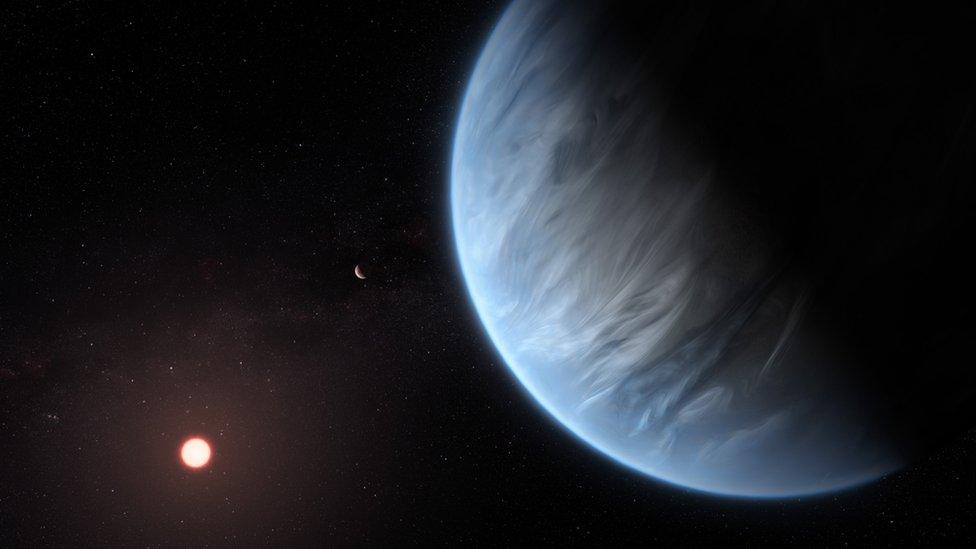

Artwork: The new planets are between the size of Neptune, in the foreground, and the Earth

Over the past thirty years, astronomers have discovered thousands of star systems. But none of them are so well suited to study how planets formed. The planets' near identical size and the system's undisturbed nature are gold dust for astronomers because they make it much easier to compare and contrast them. That will help build up a picture of how they first formed and how they evolved.

The system also has a bright star which will make it easier to look for life signs in the planets' atmospheres.

All six of the new planets are what astronomers call "sub-Neptunes", which are larger than the Earth and smaller than the planet Neptune (which is four times wider than the Earth). The six newly discovered planets are between two and three times the size of Earth.

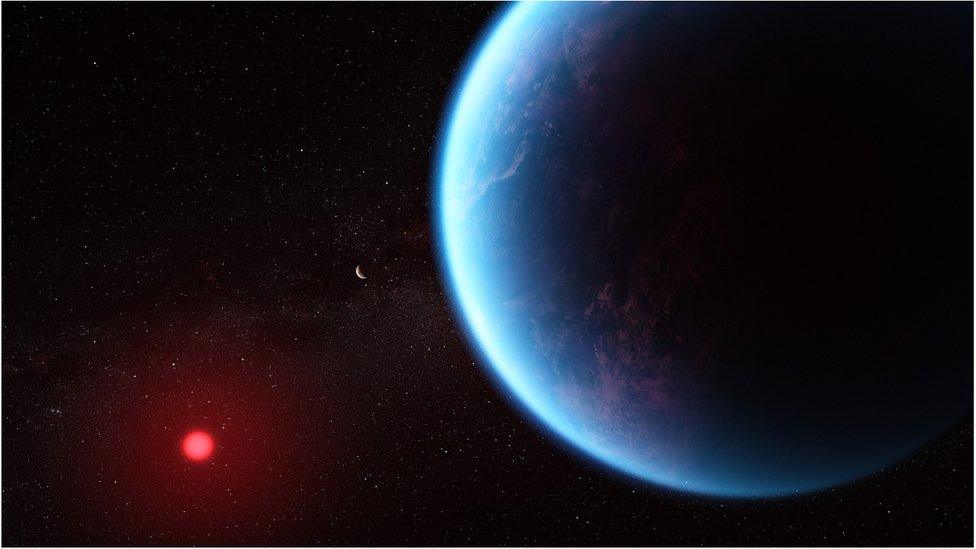

Interest in the new findings has been supercharged since the discovery in September that a sub-Neptune planet, called K2-18b, in another star system, has an atmosphere with hints of a gas that on Earth is produced by living organisms. Astronomers call this a biosignature.

Artwork: A sub-Neptune planet called k2-18b was found to have hints of life in September

Although our own solar system does not contain any sub-Neptunes, they are thought to be the most common type of planet in the galaxy. Yet astronomers know surprisingly little about these worlds.

They do not know whether they are mostly made of rock, gas or water, or critically, whether they provide conditions for life.

Finding out these details is "one of the hottest topics in the field" according to Dr Luque, adding that the discovery of HD110067 gives his team the perfect opportunity to answer that question relatively quickly.

"It could be a matter of less than ten years," he told BBC News.

"We know the planets, we know where they are, we just need slightly more time, but it will happen."

If the team's next round of observations indicates that sub-Neptunes can also support life, it greatly increases the number of possible habitable planets and therefore increases the chances of detecting signs of life on another world sooner rather than later.

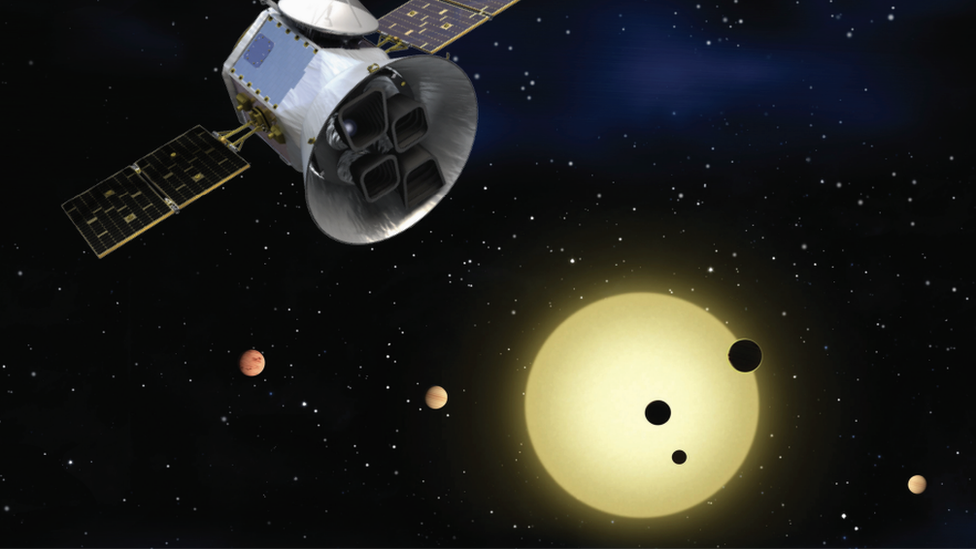

Artwork: The planets were found using Nasa's TESS space telescope

The race is now on to detect biosignatures on one of the six new sub-Neptunes, or dozens of others detected by rival groups. With a battery of new telescopes with enhanced capabilities and others about to come online, many astronomers believe that we may not have too long to wait for that moment.

The planets were detected using NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and ESA's CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (Cheops).

Follow Pallab on X, external, formerly known as Twitter.

Related topics

- Published30 September 2023

- Published12 September 2023