White House wants Moon to have its own time zone

- Published

The White House wants US space agency Nasa to develop a new time zone for the Moon - Coordinated Lunar Time (LTC).

Because of the different gravitational field strength on the Moon, time moves quicker there relative to Earth - 58.7 microseconds every day.

This might not seem like much, but it can have a significant impact when trying to synchronise spacecraft.

The US government hopes the new time will help keep national and private efforts to reach the moon co-ordinated.

Prof Catherine Heymans, Scotland's Astronomer Royal, told BBC Radio 4's Today programme: "This fundamental theory of gravity in our Universe has an important consequence that time runs differently in different places in the Universe.

"The gravity on the Moon is slightly weaker and the clocks run differently."

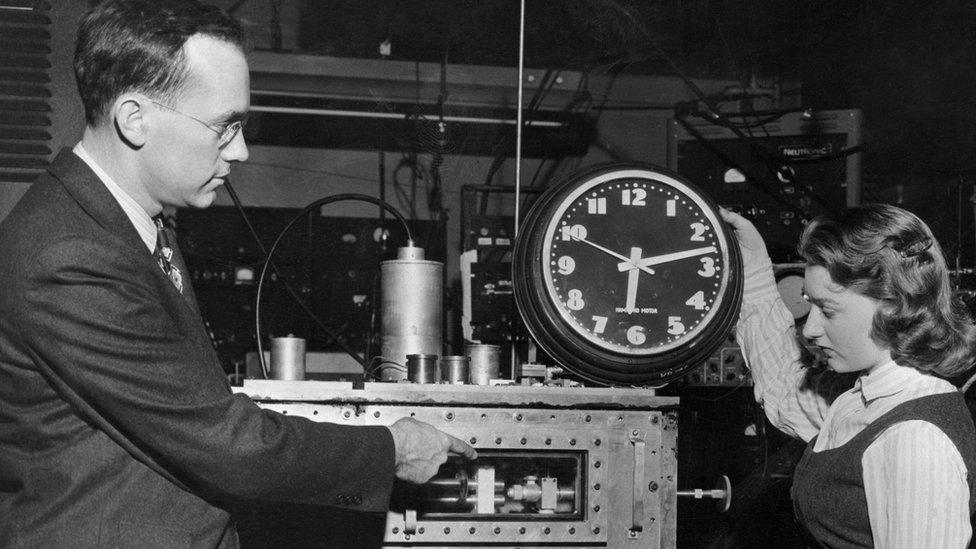

Time is currently measured on Earth by hundreds of atomic clocks stationed around our planet which measure the changing energy state of atoms to record time to the nanosecond. If they were placed on the Moon, over 50 years they would be running one second faster.

"An atomic clock on the Moon will tick at a different rate than a clock on Earth," said Kevin Coggins, Nasa's top communications and navigation official.

"It makes sense that when you go to another body, like the Moon or Mars, that each one gets its own heartbeat," he said.

An early atomic clock "maser", in the mid-1950s

But Nasa is not the only one trying to make lunar time a reality. The European Space Agency has also been developing a new time system for a while. There will need to be agreement between countries and a centralised co-ordinating body - currently this is done by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures for time on Earth.

At the moment on the International Space Station, Coordinated Universal Time is used because it remains low in orbit. Another element that countries will have to agree on is where the new time frame begins from and to where it extends.

The US wants LTC to be ready by 2026 in time for its crewed mission to the Moon.

Artemis-3 will be the first mission to return to the Moon's surface since Apollo 17 in 1972. It is set to land at the lunar south pole, which is thought to hold vast stores of water-ice in craters that never see sunlight.

Locating and directing this mission requires extreme precision down to the nanosecond, errors in navigation which could risk spacecraft entering the wrong orbits.

But Artemis-3 is also one of numerous planned national missions to the Moon as well as private endeavours. If time is not co-ordinated between them it could lead to challenges in sending data and communication between spacecraft, satellites and Earth.

Related topics

- Published9 January 2024

- Published24 September 2023