Peter Higgs obituary: the shy man who changed our understanding of the Universe

- Published

Prof Peter Higgs was best known for that mysterious-sounding thing nicknamed the 'God particle' - or just simply, and probably better-put, the Higgs boson.

He came up with the revolutionary idea in the 1960s when he wanted to explain why the basic building blocks of the Universe - atoms - have mass.

His theory about what binds the Universe together, which other scientists also worked on at the same time, sparked a 50-year search for the Holy Grail of physics.

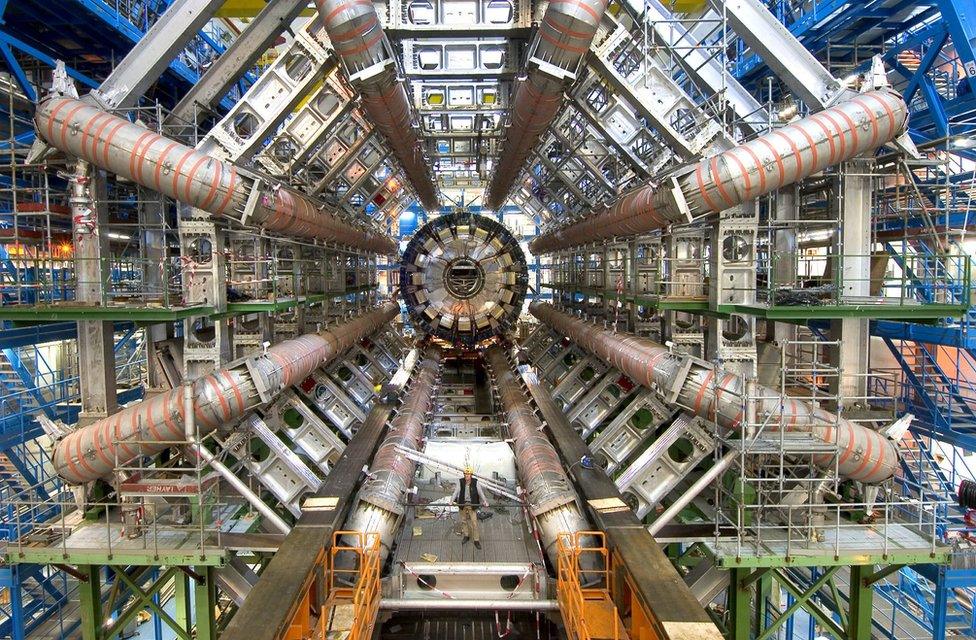

The particle was finally discovered in 2012 by scientists using the Large Hadron Collider at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (Cern) in Switzerland. It completed what is called the standard model of particle physics.

A famously shy man, he told journalists: "It's very nice to be right sometimes."

His work earned him the Nobel Prize for physics a year later.

Peter Higgs was born in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1929. At school in Bristol he was a brilliant student who won prizes for his science work - though it was in chemistry, not physics.

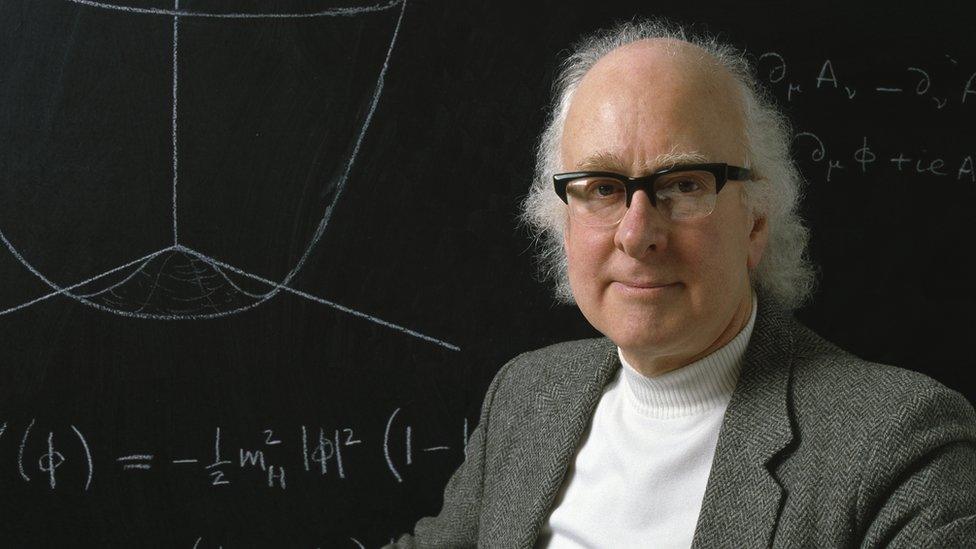

He completed a PhD at King's College in London but was beaten to a job there by his friend. Instead he went to the University of Edinburgh where he continued to ask the question: why do some particles have mass?

His theory struggled to find a place in scientific journals - partly because few understood it - but it was finally published in 1964.

Despite rumours about "Eureka" moments, he said his theory was formed over years.

Peter Higgs spent much of his life in Edinburgh

Two other groups of scientists also published work at that time about the same idea.

But the particle became known as the Higgs boson - and for 50 years scientists looked for it using some of the most spectacular technology on Earth.

Prof Higgs retired from the University of Edinburgh in 2006, but he continued to watch developments at Cern in Geneva, where scientists were using the Large Hadron Collider to look for the Higgs boson.

Cern's Large Hadron Collider Atlas detector under construction in Geneva

The particle accelerator, built at a cost of $10bn (£8bn), was the most powerful yet. It was considered the machine that could prove - or disprove - Prof Higgs's theory.

The boson had been nicknamed the 'God particle' by the media, after a book by Nobel laureate Leon Lederman. Scientists object to the term because they say religion has no role to play in evidence-based physics.

In 2012 physicists at Cern finally announced to great fanfare that they had discovered the Higgs boson.

An advance notice had been sent: "Peter should come to the CERN seminar or he will regret it." He changed travel plans to visit Geneva for the stunning announcement.

"It's been a long wait but it might have been even longer, I might not have been still around," Prof Higgs said. "At the beginning I had no idea whether a discovery would be made in my lifetime."

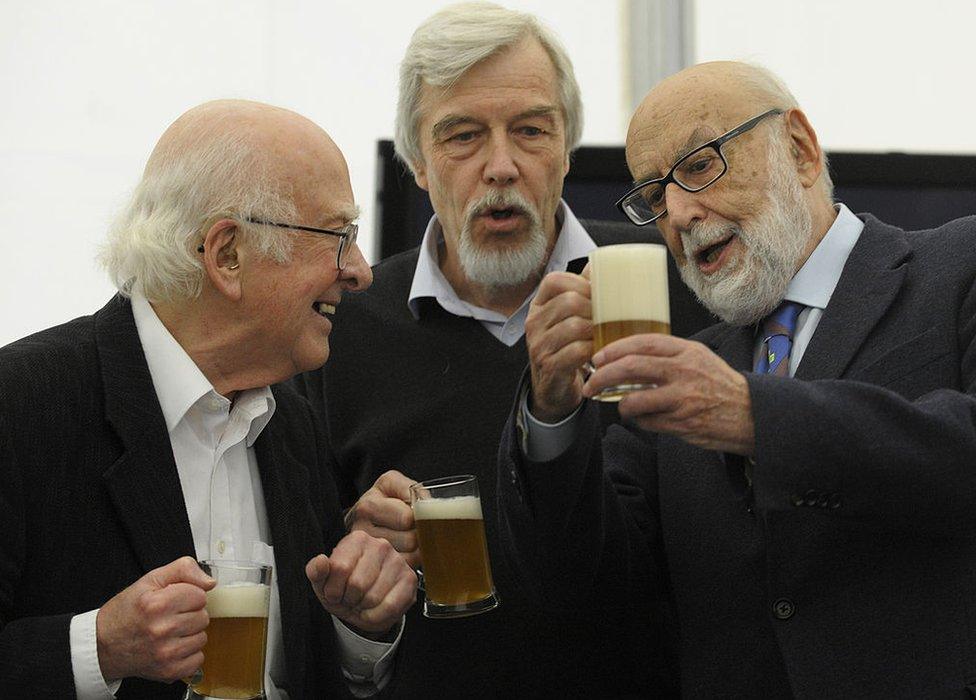

Peter Higgs (l) worked with eminent scientists around the world including Francois Englert (r) and Rolf Heuer (c)

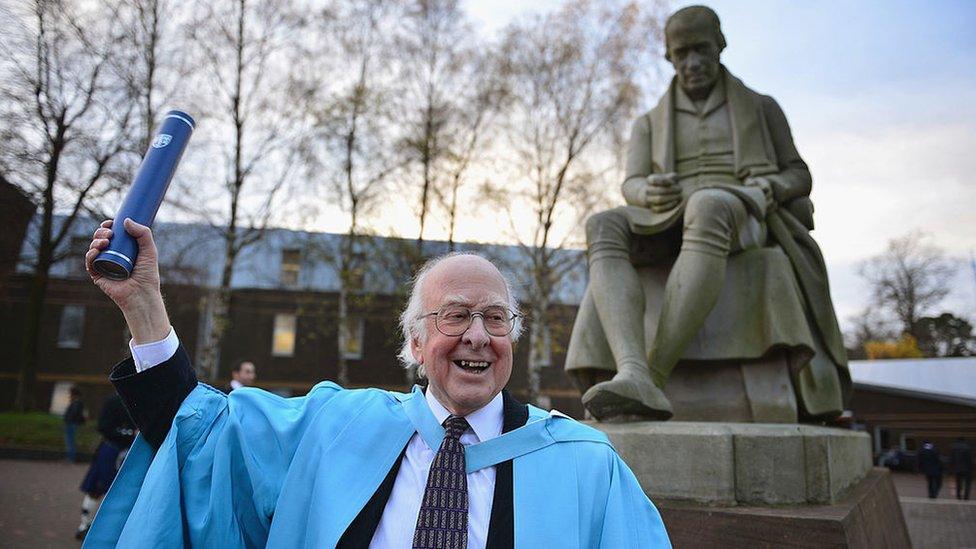

A year later the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences tried to call him. It's become a trope that winners miss the crucial phone call telling them they have been awarded a Nobel Prize. But Prof Higgs did not even own a mobile phone. The announcement was made in his absence.

A neighbour stopped him in the street to break the news that he had won - alongside Belgian physicist Francois Englert.

He was known first for the boson, but second for his shy and low-key personality - more interested in his work than fame.

Oxford emeritus professor Ken Peach talked about returning from a conference where scientists were referring constantly to Prof Higgs.

"I saw Peter in the coffee lounge and said 'Hey Peter! You're famous!'" He responded with a diffident smile.

And some friends feel Prof Higgs did not make the kind of impact that might be expected of a physicist of his ability.

"I wouldn't say he was shy," said Prof Michael Fisher, who died in 2021.

"I might say that he was a little too retiring perhaps for the good of his own career."

Pallab Ghosh goes inside the largest particle accelerator in the world - which discovered the Higgs boson.