Brightest-ever cosmic explosion solved but new mysteries sparked

- Published

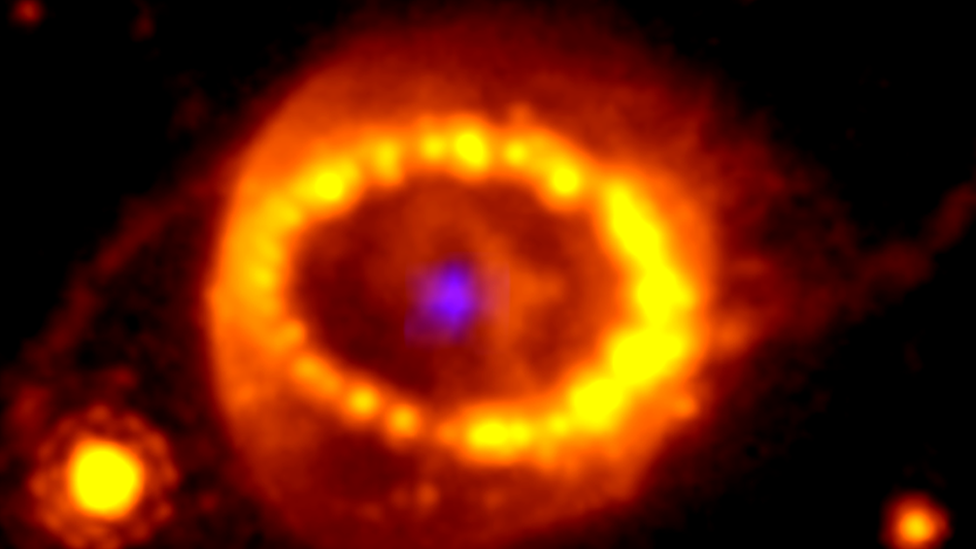

Artwork of the brightest cosmic explosion of all time

Researchers have discovered the cause of the brightest burst of light ever recorded.

But in doing so they have run up against two bigger mysteries, including one that casts doubt on where our heavy elements - like gold - come from.

The burst of light, spotted in 2022, is now known to have had an exploding star at its heart, researchers say.

But that explosion, by itself, would not have been sufficient to have shone so brightly.

And our current theory says that some exploding stars, known as supernovas, might also produce the heavy elements in the universe such as gold and platinum.

But the team found none of these elements, raising new questions about how precious metals are produced.

Prof Catherine Heymans of Edinburgh University and Scotland's Astronomer Royal, who is independent of the research team, said that results like these help to drive science forward.

"The Universe is an amazing, wonderful and surprising place, and I love the way that it throws these conundrums at us!

"The fact that it is not giving us the answers we want is great, because we can go back to the drawing board and think again and come up with better theories," she said.

Supernovas occur when large stars die resulting in powerful explosions

The explosion was detected by telescopes in October 2022. It came from a distant galaxy 2.4 billion light-years away, emitting light across all frequencies. But it was especially intense in its gamma rays, which are, in general, a more penetrating form of X-rays.

The gamma ray burst lasted seven minutes and was so powerful that it was off the scale, overwhelming the instruments that detected them. Subsequent readings showed that the burst was 100 times brighter than anything that had ever been recorded before, earning it the nickname among astronomers of the Brightest Of All Time or B.O.A.T.

Gamma ray bursts are associated with exploding supernovas, but this was so bright that it could not be easily explained. If it were a supernova, it would have had to have been absolutely enormous, according to the current theory.

The burst was so bright that it initially dazzled the instruments on Nasa's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The telescope had only recently become operational, and this was an incredible stroke of luck for astronomers wanting to study the phenomenon because such powerful explosions are calculated to occur once every 10,000 years.

As the light dimmed, one of JWST's instruments was able to see there had indeed been a supernova explosion. But it had not been nearly as powerful as they expected. So why then had the burst of gamma rays been off the scale?

All the gold on Earth was produced in cataclysmic explosions in outer space

Dr Peter Blanchard, from Northwestern University in Illinois in the US, who co-led the research team, doesn't know. But he wants to find out. He plans to book more time on JWST to investigate other supernova remnants.

"It could be that these gamma ray bursts and supernova explosions are not necessarily directly linked to each other and they could be separate processes going on," he told BBC News.

Dr Tanmoy Laskar, from the University of Utah and co-leader of the study, said that the B.O.A.T's power might be explained by the way in which jets of material were being sprayed out, as normally occurs during supernovas. But if these jets are narrow, they produce a more focused and so brighter beam of light.

"It's like focusing a flashlight's beam into a narrow column, as opposed to a broad beam that washes across a whole wall," he said. "In fact, this was one of the narrowest jets seen for a gamma ray burst so far, which gives us a hint as to why the afterglow appeared as bright as it did".

Theory rethink

But what about the missing gold?

One theory is that one of the ways heavy elements - such as gold, platinum, lead and uranium - might be produced is during the extreme conditions that are created during supernovas. These are spread across the galaxy and are used in the formation of planets, which is how, the theory goes, the metals found on Earth arose.

There is evidence that heavy elements can be produced when dead stars, called neutron stars collide, a process called a kilonovae, but it's thought that not enough could be created this way. The team will investigate other supernova remnants to see if heavy elements still can be produced by exploding stars but only under specific conditions.

But the researchers found no evidence of heavy elements around the exploded star. So, is the theory wrong and heavy elements are produced some other way, or are they only produced in supernovas under certain conditions?

"Theorists need to go back and look at why an event like the B.O.A.T is not producing heavy elements when theories and simulations predict that they should," says Dr Blanchard.

The research has been published in the journal Nature Astronomy., external

Follow Pallab on X,, external formerly known as Twitter

Related topics

- Published23 February 2024