Nasa: 'New plan needed to return rocks from Mars'

- Published

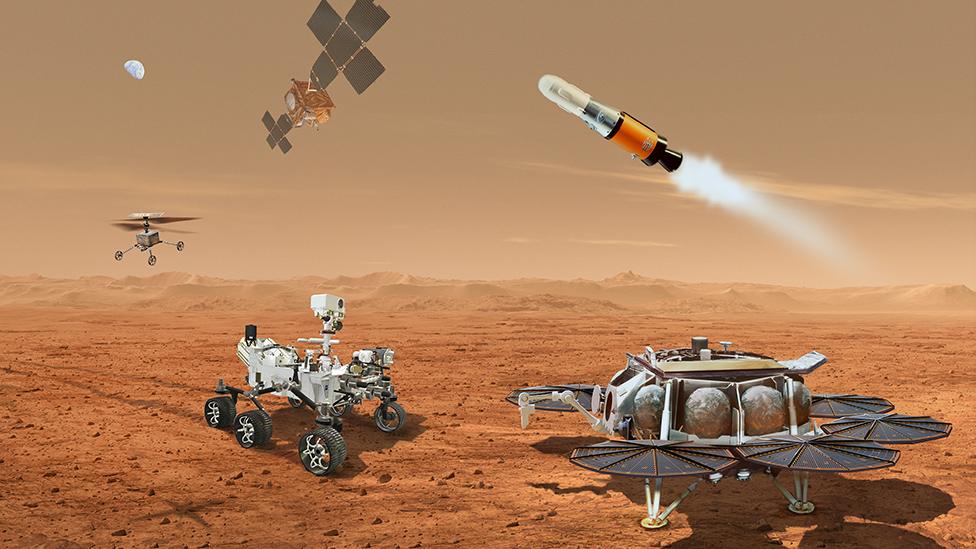

Returning Mars samples is an immensely complex undertaking that will take years

The quest to return rock materials from Mars to Earth to see if they contain traces of past life is going to go through a major overhaul.

The US space agency says the current mission design can't return the samples before 2040 on the existing funds and the more realistic $11bn (£9bn) needed to make it happen is not sustainable.

Nasa is going to canvas for cheaper, faster "out of the box" ideas.

It hopes to have a solution on the drawing board later in the year.

Returning rock samples from Mars is regarded as the single most important priority in planetary exploration, and has been for decades.

Just as the Moon rocks brought home by Apollo astronauts revolutionised our understanding of early Solar System history, so materials from the Red Planet are likely to recast our thinking on the possibilities for life beyond Earth.

But Nasa now acknowledges the way it's going about achieving the samples' return is simply unrealistic in the present fiscal environment.

"The bottom line is that $11bn is too expensive, and not returning samples until 2040 is unacceptably too long," Nasa administrator Bill Nelson told reporters in a Monday teleconference.

The former US senator said he would not allow other agency science missions to be "cannibalised" by the Mars project.

He is therefore seeking fresh thinking from within Nasa and from industry.

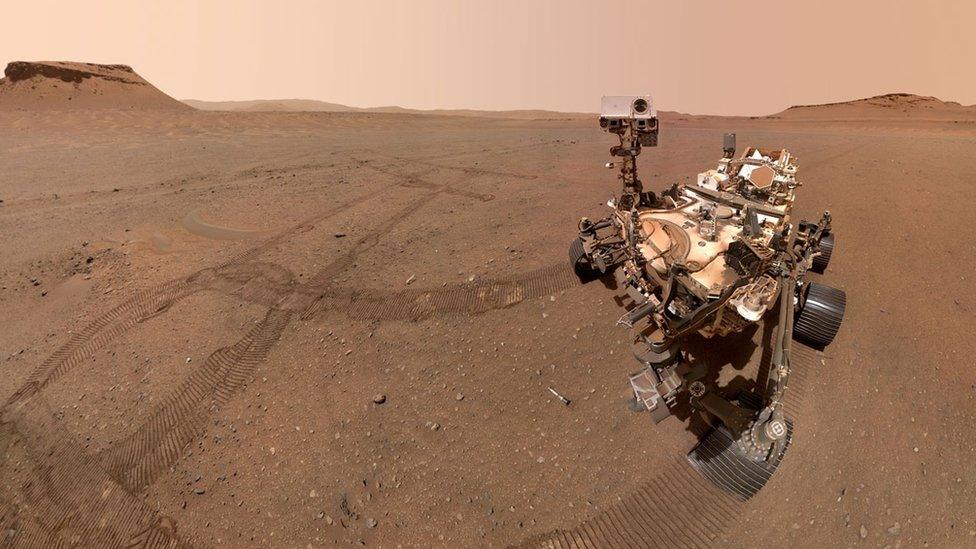

The Perseverance rover is collecting the rock samples that would be returned to Earth

The Mars Sample Return, or MSR, programme is a joint endeavour with the European Space Agency (Esa).

The present architecture is already in play, in the sense that the rock samples to be returned home are in the process of being collected and catalogued on Mars today by Nasa's Perseverance rover.

A dedicated follow-up mission was due to be launched later this decade that would carry a rocket to the surface of the Red Planet.

Once loaded into this ascent vehicle, Perseverance's samples would then be blasted skyward to rendezvous with a European-built spacecraft that could catch them and head for Earth.

It was envisaged that roughly 300g of Martian material would land in a capsule in the western US state of Utah in 2033.

But an independent review that reported in September last year found faults with the way the mission design was being implemented. It doubted the schedule could be maintained and, even so, the cost was likely to balloon to somewhere between $8bn and $11bn.

Artwork: Europe's major contribution is an orbiter that would bring the samples home

In its response published on Monday, Nasa doesn't disagree with the assessment. The current architecture can be simplified somewhat but if the samples are to come home before 2040, a new approach is needed.

"We are looking at out-of-the-box possibilities that could return the samples earlier and at a lower cost," said Dr Nicola Fox, the director of Nasa's science directorate.

"This is definitely a very ambitious goal, and we're going to need to go after some very innovative new possibilities for design, and certainly leave no stone unturned."

Those new possibilities could include a smaller, simpler Mars rocket, she said.

Dr Fox told BBC News that Esa remained central to the endeavour. Indeed, it's likely Europe's significant contribution - the Earth Return Orbiter (ERO) - will still be launched, albeit at a slightly later date than currently envisaged, possibly in 2030.

Dr Orson Sutherland, Esa's Mars exploration group leader, said his organisation would meticulously review Nasa's response plan.

"Our priority remains ensuring the best path forward to achieve MSR's ground-breaking scientific objectives and lay the groundwork for future human missions to Mars," he said.

Mr Nelson emphasised that Nasa remained totally committed to MSR.

It needed, however, to fit within a sustainable budget envelope, which he described as somewhere between $5bn and $7bn.

The minerals in some of Jezero Crater's rocks were probably laid down in the presence of lake water

The overwhelming scientific imperative behind MSR was underlined in recent days by the latest investigations of Perseverance.

The robot is working in a wide crater called Jezero, which looks to have held a large lake about 3.8 billion years ago - a highly promising scenario for the existence and preservation of microbial organisms.

Perseverance has been drilling and caching rocks that appear to have been laid down at the margin of the lake.

One of the rover's senior scientists, Prof Briony Horgan from Purdue University, said these samples were particularly exciting.

"Right now onboard Perseverance, we're carrying three samples of silica and carbonate-cemented rocks; and on Earth, both of those minerals can be fantastic for preserving ancient signatures of life," she told BBC News.

"We think it's possible that some of the samples are sandstones laid down in the ancient lake, but are still evaluating other origins as well. Either way, these rocks are the exact types of samples that we came to Mars to find, and we very much want to get them back to our labs on Earth."