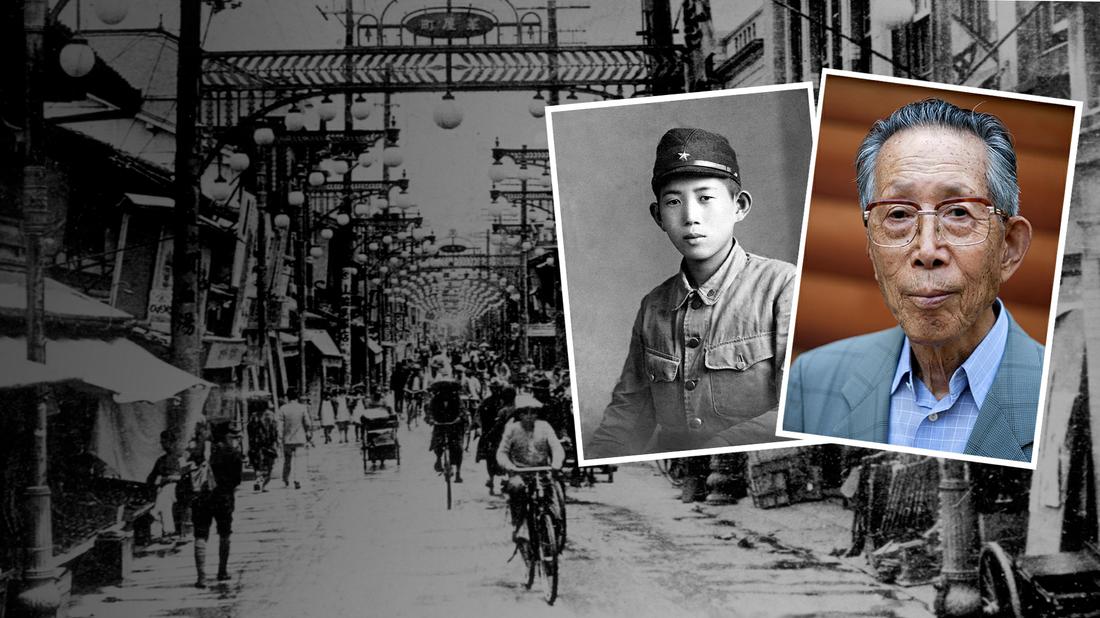

When time stood still

A Hiroshima survivor's story

Shinji Mikamo lost everything when the nuclear bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, except his father's watch. He did not blame the Americans for the cataclysm though - and later, when the watch was stolen, he showed his daughter once again his powers of forgiveness.

As a child, when the family bathed together, in the Japanese way, Akiko Mikamo never asked about her father's missing ear or the scars on her parents' bodies. "I didn't think about it," she says. "It was very natural."

Her mother never spoke about the bomb - as a traditional Japanese woman she "learned to swallow her pain so as not to burden others". But Akiko grew up listening to her father's stories of that day, which she has now collected in a book. Above all, he always taught her it was wrong to hate:

Americans are not to blame, the war is to blame. People's unwillingness to understand those with different values - that's to blame."

The pilot of the Enola Gay had only been following orders, he pointed out, and risking his own life in the process.

The last half hour

Summers in Hiroshima were suffocating, and the morning of 6 August 1945 was no different from any other - hot and humid. Shinji Mikamo had taken the day off from his work as an apprentice electrician in the army to help his father clear their home, which was soon to be demolished. Months of air raids had caused devastating fires in cities across Japan, so the government had decided to create firebreaks. The Mikamos' house was one of those to be flattened. "It makes no sense," growled Shinji's father, Fukuichi - but orders were orders.

Shinji's mother, Nami, who was gravely ill, had been evacuated to the countryside, and his older brother Takaji was fighting in the Philippines. So 19-year-old Shinji and his father were living alone in the city. Before long Shinji himself was due to end his apprenticeship and join the army, so he too would most likely move away.

They set to work after the usual war-time breakfast of millet and barnyard grass porridge. Fukuichi would joke:

I wake up early nowadays because I’m fed bird food."

Fukuichi looked at the pocket watch he always carried with him, a round watch that fitted in the palm of his hand, the silver casing worn smooth by his touch. It was 07:45. Shinji climbed up to the roof to remove the clay tiles. Neighbours had offered the homeless pair a room, but there was no toilet. They needed the tiles to make a roof for an outhouse.

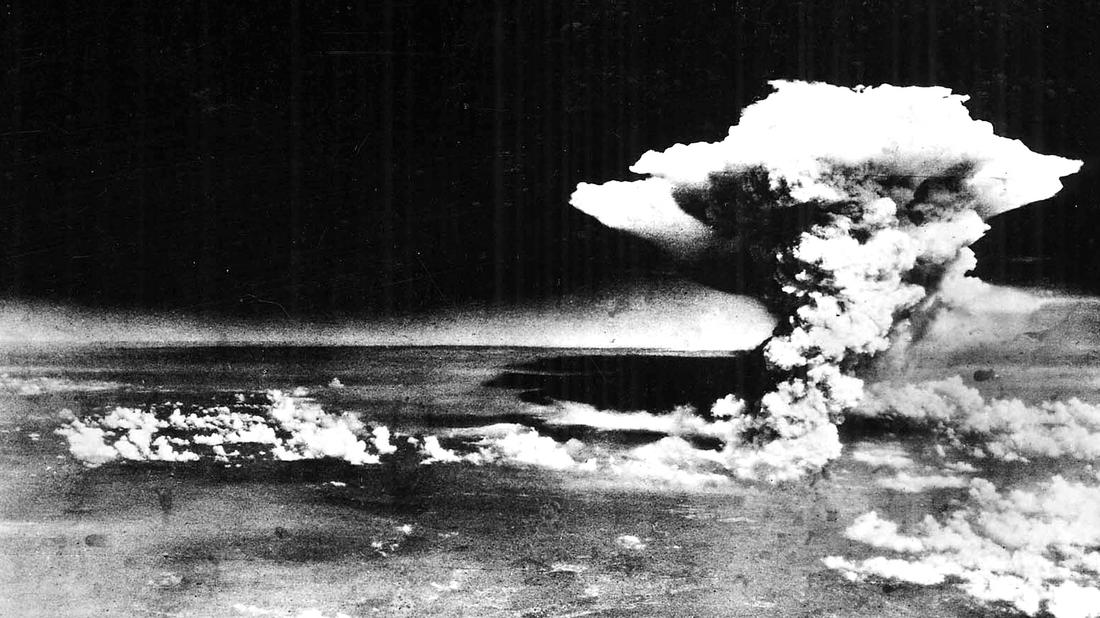

There wasn't a cloud in the sky. From his vantage point Shinji looked out over the gleaming city. Down in the yard, Fukuichi called up to his son not to day-dream. Shinji quickened his pace. At nearly 08:15 he remembers lifting his right arm to wipe the sweat off his brow, when suddenly a blinding flash filled the sky. He recalls:

Suddenly I was facing a gigantic fireball. It was at least five times bigger and 10 times brighter than the sun. It was hurtling directly towards me, a powerful flame that was a remarkable pale yellow, almost the colour of white."

"The deafening noise came next. I was surrounded by the loudest thunder I had ever heard. It was the sound of the universe exploding. In that instant, I felt a searing pain that spread through my entire body. It was as if a bucket of boiling water had been dumped over my body and scoured my skin."

Shinji was thrown into darkness as he was buried under the house. He became aware of his father's voice calling, coming closer. Although he was 63 years old, Fukuichi was strong - he pulled his son from under the rubble and put out the flames that were licking his body. Shinji's chest and the right side of his body were completely burned.

"My skin hung off my body in pieces like ragged clothes," he says. The raw flesh underneath was a strange yellow colour, like the surface of a sweet cake his mother used to make.

After the apocalypse

"My father and I looked at each other, frozen," Shinji says. The city around them had disappeared, reduced to ash and rubble. Shinji couldn't understand what had happened. Had the sun exploded? His father guessed the real cause immediately. "They have demolished all the houses for us," he said. "I guess they saved us some labour." He laughed his throaty laugh.

There was no time to stand and talk, though. The ruined city was now on fire and they had to take refuge. Shinji and Fukuichi headed through the unfamiliar post-nuclear landscape to the river. While there, as bodies floated past face-down, they soon witnessed another strange and terrifying phenomenon. The many fires across the city had created storm-force winds which now combined in a tornado - "a dark monster", remembers Shinji - that sucked up everything in its path. It picked up and threw down parts of collapsed houses, furniture, even water from the river. As it approached, people clung to whatever they could for safety.

This new world was hard to understand, but once the fire and tornado had died down, Shinji and his father set off across a bridge in search of shelter. Walking was agony, not only because of his burned flesh, but because of the large numbers of dead and dying bodies on the ground. "My feet were charred and clumsy. Every step or so, I would unintentionally hit an arm or a leg and hear the person below me wince in pain. I felt like a vulture. Crossing that bridge, and leaving all those wounded people behind to die," Shinji says.

Slowly, with my heart breaking into countless pieces, I stumbled forward. I did my best to follow exactly in my father's footsteps, hoping and believing he would know the path to save us both."

The bomb had laid waste to Hiroshima. Out of its 45 hospitals only three still functioned. There was no help. No medicine. No pain relief. Fully exposed on the roof, Shinji had been only three-quarters of a mile from the epicentre of the explosion.

Shinji attributes his survival mostly to his father's strength. Whenever he wanted to give up, Fukuichi scolded him. "Don't slip into weakness so easily," he said. "We've made it through the worst."

With barely any skin to protect him, a little of Shinji's flesh scraped off with almost every step. When they were too weak to walk, he and his father would crawl instead. It took hours to cover short distances. He pleaded with his father to let him die - but Fukuichi was resolute:

You want to die? Don't say that word so lightly. As long as you stay alive, you will recover one day. The day will come. Just a bit more to go."

And eventually, they had a crucial stroke of luck. Returning again to the district where they had lived, they were recognised by Shinji's friend and fellow army apprentice, Teruo. As a civilian employed by the army, Shinji had some privileges, so Teruo was able to start pulling strings to get him evacuated for treatment.

On 9 August, three days after the bombing, Shinji and his father were lying on the floor of a school in a village outside the city, along with dozens of other badly-wounded people, when Shinji’s thoughts turned to a disturbing incident the day before. As he and his father had made their way down from the Toshogu Shrine, two soldiers had barred their way, and told them to go back up the steps - an agonising prospect. When Fukuichi protested, one of the soldiers spat in his face and told him to go to hell. In a society where the elderly were revered, this was deeply shocking, and yet Fukuichi had held in his anger and turned away - staying alive was more important.

It took them hours to make their way out through the back of the shrine, down a slope covered in prickly bushes and the splintered remains of wooden gate-posts. Shinji cursed the soldiers with every painful step.

Shinji just couldn't understand how the soldiers could have treated them like that. Consumed with anger and hatred, he turned to his father for an explanation. "They were demons, weren't they?" he said. "They were evil. Maybe even worse than the American bombers." Fukuichi replied calmly:

We are in hell right now. No wonder we see demons."

He reminded his son of the angels they had come across - the neighbour who had made them miso soup, Teruo and his crucial intervention, the villagers who were tending to the wounded all around them. Shinji was forced to accept that goodness still existed. He fell asleep that night with tears of relief in his eyes, imagining the face of the Buddha.

Two days later, soldiers came to take Shinji to a field hospital. Father and son had survived for five days wandering together through post-apocalypse Hiroshima, but now they had to part. Fukuichi’s unwavering gaze followed his son as he was carried out to a waiting army truck.

When Shinji arrived in the hospital, the wounds on his leg were now badly infected and needed draining of pus and maggots. His greatest pain, however, came from bed sores caused by days of lying on the ground. One morning, a hospital volunteer noticed him wincing, and promised she would bring him some pillows from home.

The hope he felt at her promise soon turned to anger and despair as he waited all day for her return. "I felt hatred for this woman who had betrayed me so cruelly," he remembers. But she did come back, late in the evening, with the promised pillows - she had been unavoidably delayed. "The moment I saw her, my anger turned to shame," he says. "How could I have been so hateful in my thoughts?"

It was a turning point.

He became determined never to make that mistake again. "She was an angel who had returned to rescue me from my worst pain," he says. "She was also an angel who rescued me from the depths of my own judgmental anger."

One morning, Shinji awoke to an unusual sight - the soldiers at the hospital were no longer wearing their swords. It was 16 August, a week after a second atomic bomb had been dropped on Nagasaki. Japan had surrendered on 14 August. The war had ended.

Fragment from the past

Shinji was released from hospital in October 1945. A month earlier he had managed to send a postcard to his mother to let her know he was still alive. Now he went in search of his father. He found the ruins of their old home - identifiable thanks to the distinctive patterns on the family's shattered rice bowls. Sifting through the charred remains, he made a heart-stopping discovery - a familiar round disk, caked with dirt and soot.

I clasped my hand around the metal mass and lifted my father's pocket watch from the debris. I recognised our house key chained to it. I turned the watch face up. The glass had been blown off, as had the watch hands. The metal was rusted and burned. The unimaginable intense heat that reached several thousand degrees Fahrenheit from the blast had fused the shadows of the hands into the face of the timepiece, slightly displaced, leaving distinct marks where the hands had been at the moment of the explosion. It was enough to clearly see the exact moment the watch stopped."

The watch had recorded the moment Shinji's world had been blown apart - 08:15. "It had stopped working at the very moment of the blast, forever marking that moment in time."

Holding the watch in his hands, he suddenly sensed he would never see his father again. The thought hit him "like another atomic blast", he says. Standing on the ruins of his home, wearing someone else's clothes, he thought of the beautiful photographs taken by his father, a professional photographer. These were now ash beneath his feet.

The watch was his only link to a family that had been wiped out. Although he didn't know it yet, his mother Nami had died a few days after receiving his postcard, and his brother Takaji had been killed in action in the Philippines. What happened to his father, he never discovered.

As an orphan of war, Shinji struggled to survive and find a place in society. In Japan then, "the harmony and connections of family were everything", says his daughter, Akiko. A man without family was no better than a criminal. So when he sought permission to marry Miyoko, the sister of a childhood friend, her father said No. The couple were forced to elope.

Their first daughter, Sanae, was born three years after the bomb. Healthy at first, she contracted polio and encephalitis and became severely disabled. They had their second daughter, Akiko, in 1961, and three years later a third, Keiko.

The watch remained Shinji's only family heirloom. He felt it contained a part of his father's soul. And yet, in 1949, when Hiroshima was officially designated an International Peace Memorial City, he decided to donate it to the Peace Memorial Museum.

I wanted the watch and my father's name to be widely seen and known as a reminder of both the destruction and the heroism that were displayed that fateful August day"

He felt Fukuichi would have approved.

City of peace

At the time, many citizens were outraged at their city's new status – they were too angry to appreciate talk of peace or pacifism - but Shinji never bore a grudge.

"There was an endless supply of anger and bitterness to be found, if one wanted to find it," he says. "But I did not." He felt no good could come from holding on to animosity. "These were the blinders that provoked conflict, not soothed it," he says.

I wanted to see enemies become allies. I wanted peace."

Akiko saw the pocket watch only once, on a school trip to the museum at the age of seven - she remembers feeling much closer then to the grandfather she had heard about in her father's tales. Then, in 1985, the watch was sent to New York to be part of a permanent commemorative exhibit in the United Nations headquarters.

For years, it gave Shinji great pleasure and pride to think of the watch telling its story about Hiroshima to museum visitors in New York.

In 1989, when Akiko travelled to the US to study psychology, the first thing she wanted to do was to see her grandfather's watch. A tour guide took her to the case containing the precious pocket watch – and it turned out to be empty. There was nothing there but the label. Confused, the guide went to find out what had happened, only to come back with the terrible news that it was missing - presumed stolen. Nobody had informed the museum in Hiroshima, or her father.

Shaking with rage, Akiko immediately called Shinji in Japan. He had no words at first, but soon turned to his old mantra to calm his daughter down. "Akiko, don't hate them," he said. "It's easy to blame somebody when you suffer a significant loss."

The watch had been the only tangible possession that connected him to his father and all his ancestors, but as he tried to calm down his stricken daughter in New York, he told her it was merely an object.

Losing it didn't mean losing the spirit they had imbued it with. It didn't mean their connection to their ancestors was gone. It didn't mean his father's story could not be shared with the world. He told Akiko:

When you lose something you will gain something."

He had to remind himself of that Japanese saying many times.

And losing the pocket watch did turn out to be a blessing in the end. Five months after it went missing, the family, and the Japanese government, received a letter of apology from the UN. This was reported on the news in Japan, with the result that distant relatives who Shinji had never known got in touch, as did friends of his father's.

They told him stories and sent him family photographs from before the war - each one was like getting back a small piece of the family he had lost. He recalls:

For the first time since the war, I was no longer a street rat, an orphan without family connections."

Shinji's wish was always for Akiko to become "a bridge across the ocean". And she took him at his word, studying, then settling in the US, and specialising as a psychologist in cross-cultural relationships.

She sees only too clearly the problems still besetting relations between the two countries nearly 70 years after the war. "There is a lot of hatred, and grudges on both sides. It's like being a traitor. If you don't hate the enemy, you are the enemy," she says. Though of course many people take a softer line.

"Wow, your father is really something. I haven't forgiven them," Hiroshima survivors have said to her in the past. "I still hate Americans, they killed my family in front of me - but I commend your father."

In the US, she says, there are plenty of people who have no problem with Japan today, but still prefer not to think about Hiroshima.

The wisdom Shinji learned from his own experience, is something she has come to understand from a theoretical perspective. Her father, she says, made a choice to use what he went through "as an opportunity to better understand human behaviour, rather than to remain a victim to lifelong chains of anger, judgement and detachment".

Her greatest wish is that her book about her father, Rising from the Ashes - which has now been published in both the US and Japan - will encourage others to do likewise.

With the right intentions, she says, "our worst enemy of yesterday can be our best friend of tomorrow".

Ten years ago Shinji himself had an experience that proved the truth of this. On the 60th anniversary of the Japanese surrender, 14 August 2005, he was visiting Akiko at her home in San Diego. They went down to the beach for a picnic, where they ran into two surf instructors Akiko knew – American twins, who insisted on giving her 79-year-old father a lesson "for peace".

After Shinji successfully rode the waves, the surfers took him home to meet their father, a veteran of the war in the Pacific. His life, arguably, was saved by the atomic bombs, and the Japanese surrender that followed.

The two old men were the same age. They shook hands and shared a drink, and then returned to the beach. Looking out to sea, they were looking directly towards Japan.

“We stood in the water of the Pacific Ocean with candles,” says Akiko, “and took a moment of silence.”