The robberies started again on a Wednesday.

A masked man drove a stolen van through the quiet streets of Aspra Spitia in central Greece, a clutter of white buildings with black, square windows, like a game of dominoes tumbling into the Gulf of Corinth.

Parking outside a branch of the National Bank, he forced his way inside carrying an AK-47 rifle. He ordered staff to open the ATM, and snatched 150,000 euros. Then he took 100,000 euros from the cash boxes, and in moments he was gone.

It was February 2010, and the Greek economy was in crisis caused, many believed, by greed and corruption in the banks. One man was making them pay.

In October, it is alleged he robbed two banks in the same day. In Eginio, near Thessaloniki, a robber smashed through the windows of the National Bank, then did the same at the Agricultural Bank just 100 yards down the street, escaping with 240,000 euros.

And because no-one was harmed - unusual in Greek robberies - local authorities drew a conclusion:

It is highly likely this is the activity of Vassilis Paleokostas.”

In a crime spree spanning three decades, the man known to many as the Greek Robin Hood has taken millions from state-owned banks and kidnapped industrialists, while liberally distributing cash to the needy.

Though he differs from some other famous bandits - Ned Kelly, say, or Billy the Kid - by claiming to have hurt no-one during his exploits, he remains one of Europe’s most wanted men.

One of his former cellmates, Polykarpos Georgiadis recalls:

Criminals snatch purses from old ladies. Vassilis was on a different level: he is a socially accepted bandit and a hero.”

But just like the original Robin Hood, Vassilis Paleokostas is despised by the authorities he plagues. They portray him as a violent terrorist and Greek journalists have strangely shied away from telling his incredible story.

Boy from the mountain

Born in 1966, Paleokostas grew up in the village of Moschofyto, a remote cluster of shacks on a snow-capped mountain in central Greece.

There he watched his father yelling at goats and grew up idolising his older brother, Nikos. The villagers were known locally as “the heroes” explains Father Panayiotis, the local priest, not only for surviving the brutal conditions of the mountains, but for doing so without shoes.

“Vassilis may have been a thief, but never a criminal,” Panayiotis says. In these parts, bandits like Vassilis - who stole to feed his loved ones - are not always looked down upon.

When the snow grew too deep, Nikos would carry Vassilis on his shoulders three miles to the nearest school. There, the priest would thaw the frozen boy in front of the stove before any learning could begin.

In 1979, the family moved to the nearby town of Trikala. Nikos, 19, had left home to find work on the ships, and Vassilis, just 13, struggled to fill his brother’s shoes. His father, Leonidas Paleokostas, remembers:

He stood on a production line at a cheese factory for two years. He was the quiet one, very introverted.”

Through the factory window Vassilis saw the Greek economy swelling and the rich getting ever richer, as the country moved closer to joining the European Union.

One afternoon, he walked out of the cheese factory and never returned. “Vassilis suffered his bosses’ capitalist exploitation, working as a wage slave in a factory,” says his friend, Georgiadis. “So he turned against those bosses.”

“As a mountain boy, he had no skills other than stealing to make his living,” says Father Panayiotis, with characteristic generosity towards his former pupil. Between 1979 and 1986, Vassilis and his older brother, Nikos - who didn’t spend long at sea - were allegedly responsible for 27 robberies, mostly the theft of video recorders.

Vassilis, new to electricity, became hooked on action movies, often staying up all night, gripped by Rocky’s fights, Schwarzenegger’s muscles, and Clint Eastwood’s escape from Alcatraz.

Around this time, the young robber met a kindred spirit, who would turn into a major influence. “Vassilis was just a petty thief,” says Dimitrios Gravanis, the town’s chief plainclothes policeman, “until he met Costas Samaras, a.k.a. The Artist.”

Older and more sophisticated than the Paleokostas boys, Samaras was an aspiring criminal mastermind who had studied at design school and would plan elaborate robberies in a sketchbook.

Together the Paleokostas brothers and the Artist graduated to robbing jewellery stores and banks.

Gravanis recalls their first heist as a trio:

Vassilis climbed to the top of a hill and fired a rifle to get the cops’ attention. But they’d placed a huge industrial oven in front of their door.”

It took the cops vital minutes to break out of their own police station, and by the time they did the Artist and Nikos were already holding up the local jeweller.

When we finally got to our cars, they had left spikes in the road that punctured our tyres. From that moment it became my ambition to see those boys in jail.”

The moustachioed detective was a thinker who preferred to solve crimes using his brain than by beating confessions from suspects. “I lost a lot of sleep over the Paleokostas brothers,” he recalls. “I would work long nights on the case, and when I got home at 07:30, my wife was just going to work.”

But Paleokostas was impossible to catch, for one reason - he spread his cash among the poor. Gravanis explains:

He would say to a farmer, ‘Kill a pig for me to eat,’ and instead of paying 10 drachmas, he would leave 1,000.”

And so the 1980s flew by in a blur of bank raids and capers, with Vassilis distributing the proceeds to anyone who sheltered him. “Vassilis was just a kid, keen to impress his brother, Nikos, and always desperate to be a part of a real robbery,” says Gravanis.

Massive inflation in Greece saw the price of a beer quadruple between 1985 and 1992. The public grew more distrustful of government, and critical of corruption inside the state-run banks. This swelled the numbers of those prepared to cheer on the roguish Paleokostas brothers.

An era of cat and mouse between the cops and the robbers began.

In April 1990, Paleokostas was arrested while attempting to rescue his brother from prison in Larissa by driving a stolen tank through the wall. He was imprisoned, but not for long.

In January 1991, as US President George Bush began Operation Desert Storm with air strikes against Iraq, he was busy escaping from Chalkida jail, using bed sheets to climb over the wall. But despite the riches they accrued, Vassilis preferred to live like a peasant, only spending what he needed.

He scorned flashy cars, except for getaways. One of the few expensive possessions he treasured was a mysterious golden crucifix that swung from his neck. It would later become the key to at least one successful escape.

If you steal something small you are a petty thief, but if you steal millions you are a gentleman of society.” Greek Proverb

The game changer

In June 1992, the robbers planned a heist more daring than any they had carried out before, from the hills of Meteora, a rocky outcrop studded with monasteries overlooking the terracotta rooftops of Kalambaka.

The area, inhabited continuously for 50,000 years, has traditionally been a sanctuary for hermits, bandits and fugitives like Paleokostas and his gang.

It’s a small town - the bank is just 500 yards from the local police station - but the robbers seem to have enjoyed the idea of making the cops look foolish. As Nikos peered through his binoculars, the Artist sketched the town square on a scrap of paper.

Vassilis shouted “Listia!” - Greek for “stickup” - as the three men strolled into the bank dressed in suits and sunglasses and cradling automatic weapons.

As the Artist blockaded the cops’ path with a stolen truck, a cashier pressed the silent alarm before opening the safe at gunpoint.

The Greek economy was flush, its banks loaded with borrowed cash. Inside the safe was more than they could have expected. Much more. Vassilis praised God and began filling his duffel bag.

Then came the sirens. As the group roared away in a stolen Audi towards the mountains of their childhood, the police were hot on their tails.

Vassilis tossed handfuls of cash from the window. There was chaos in the streets as clouds of bills rained down on the townspeople. In just three minutes, 125 million drachmas, worth £360,000 at the time, had been stolen from under the nose of the authorities.

It remains the biggest robbery of cash from a bank in Greek history, and maybe the only one that was shared with passers-by.

“They stole a local guy’s Nissan to get around the mountains,” recalls Gravanis. But Paleokostas returned it to the owner - with 150,000 drachmas (£430) under the carpet. “Unbelievably, the car had been polished for him,” says the detective.

Village folk in the area still remember Paleokostas fondly. “He never said very much,” an elderly lady in a coffee shop recalls. “But he always had a mischievous smile.”

The gang’s activities prompted banks to increase security, and credit cards were beginning to replace cash, making the Kalambaka haul unlikely to be repeated. Maybe for this reason, Paleokostas gave up robbing banks for a while.

One story is that he started up his own cheese factory in Bulgaria, another that he opened some shops in the Netherlands. What we know for sure is that some time later he turned his hand to kidnapping rich industrialists and holding them to ransom.

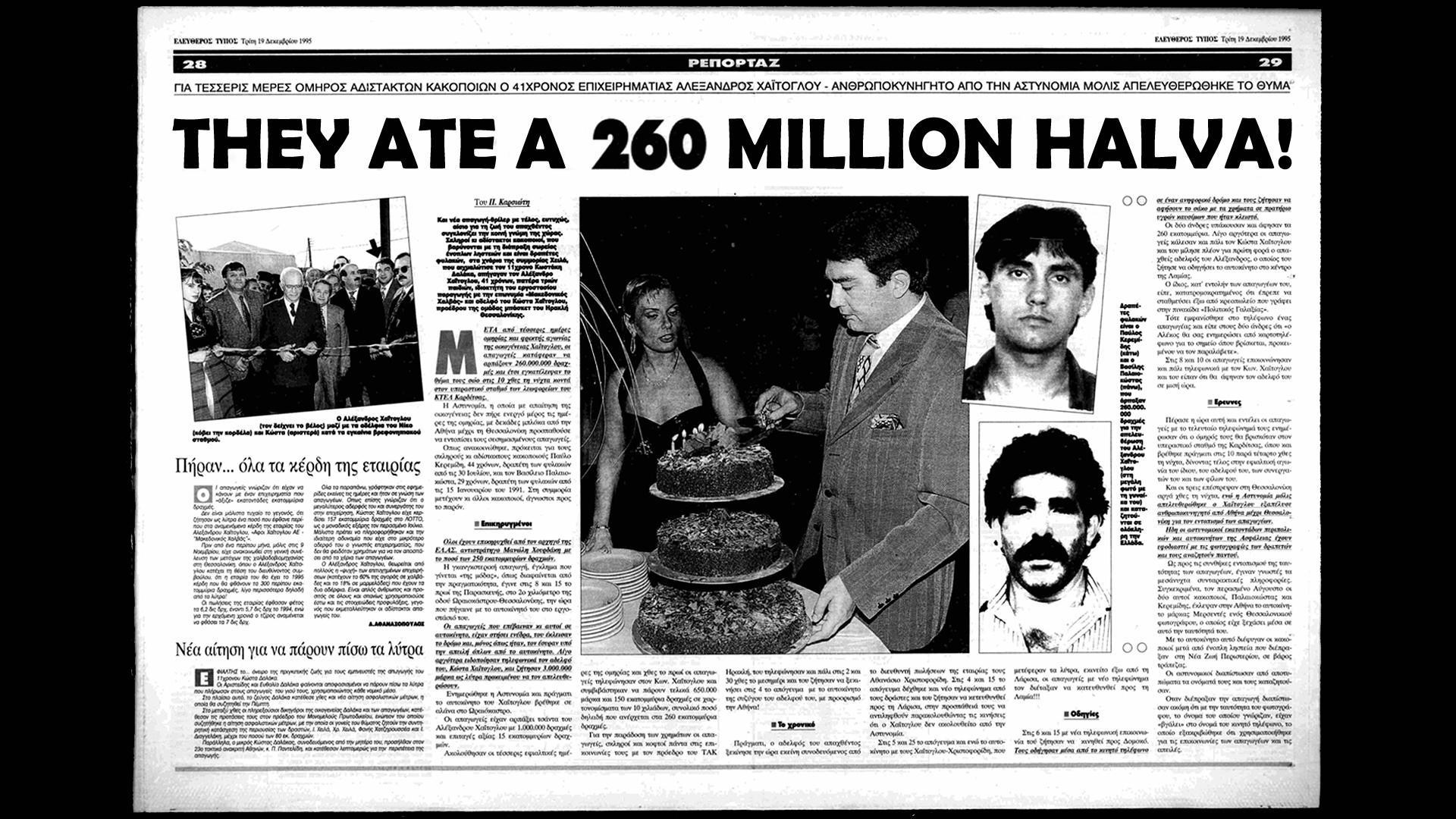

On Friday 15 December 1995 at 08:15, billionaire factory owner Alexander Haitoglou left his sprawling villa in Thessaloniki and began the short drive to his factory, where workers manufactured halva, a traditional Greek dessert made of crushed sesame seeds and honey.

Haitoglou’s car was forced off the road, and he was hustled into a high-powered Jeep by the Paleokostas brothers. Vassilis demanded more than 260 million drachma (worth £714,000 at the time, and some £1.2m in today's money) for his release. The tycoon later admitted:

It was a well-thought-out kidnapping. My kidnappers’ behaviour was not bad at all. I was not scared for myself. Actually, I enjoyed some wide-ranging discussions with the kidnappers.”

After his safe return, a newspaper headline screamed: THEY ATE A 260 MILLION HALVA!

The Greek police responded by placing an incredible bounty of 250 million drachmas on Paleokostas's head, calling the kidnappers “ruthless professionals, practising organised crime on a scale unprecedented in our country”.

But he reportedly maintained his Robin Hood routine, distributing some of the ransom among local farmers and the homeless. “He gave 100,000 drachmas to some orphan girls who needed to marry,” his father says.

In Greek villages in those days a woman couldn't get married without a dowry, and in some villages that remains true today. But, as usual, Paleokostas was handing out more cash than necessary, if his father’s claim is correct - 100,000 drachmas was a huge amount.

Paleokostas spent more than three years evading authorities, living as a fugitive high in the hills. Occasionally, in disguise, he would go for a joyride. Gravanis, the former detective, recalls:

We finally caught Vassilis after he crashed his car. He was high, smoking something, and he caused an accident.”

Onlookers rushed to call an ambulance, but the robber pleaded:

Don’t tell them who I am. I’m Vassilis Paleokostas!”

On 20 December 1999, the emergency call centre told cops:

We’ve got a man here who must have a head injury - he thinks he’s the most wanted man in Greece.”

Life inside

Corfu prison resembles a villain’s lair from the movies, a bleak stone pile perched on a cliff high above the Ionian Sea.

The food was slop, the cold stone cells overcrowded, and as soon as he arrived, Vassilis Paleokostas was reminded of the shame of his barefoot upbringing.

“I need to organise shoes for my comrades,” he told a visiting preacher, who helped him find hundreds of pairs for the shoeless prisoners.

But his time in Corfu wasn’t all good deeds. In May 2003, prison guards found a detailed plan of the jail in his cell and immediately transferred him to the maximum-security Korydallos prison near Athens.

One of Europe’s most notorious jails, Korydallos is home to murderers, war criminals and terrorists.

A little more than six years into his 25-year sentence for kidnapping and bank robbery, Paleokostas was locked up with Alket Rizai, a desperate Albanian hitman, and the two became unlikely friends. “It took 20 days to plan our escape,” Rizai told me over the phone from a jail in the city of Patras.

“Vassilis was hell-bent on getting out,” says a man known as The Warden, a tough Greek prison boss with a formidable reputation:

For instance, I found out the gold crucifix on his necklace could unscrew handcuffs. And one day I discovered a file hidden inside packets of his spaghetti.”

Instead of confiscating the file, the Warden let Paleokostas saw away at his bars for months, and took pleasure in secretly checking on his progress.

“Put away your weapons,” he told his guards, when Paleokostas finally cut through. “I want to finish this like men.” When Paleokostas tiptoed around the corner of the yard, the Warden was waiting. They traded blows under the floodlights, until the prisoner was defeated. The Warden explains:

He used poverty as an excuse to become a criminal. He started to believe this Robin Hood myth.”

By 4 June 2006, Paleokostas had already crossed off 2,358 days in his diary since the day he was jailed. At 18:15, near Athens, a commercial helicopter pilot named Karikis was boarding his white AS355N Eurocopter.

The former military pilot flew pleasure trips over Attica for the Greek rental firm, Airlift, but five minutes after take-off one of his two passengers pressed a handgun into his neck.

The sight-seeing trip was over, the man explained. He was Nikos Paleokostas, he said. And he was going to rescue his brother.

Within 10 minutes the chopper was in sight of Korydallos prison, and reducing its speed to 70 mph. “We considered hiring a pilot, but a scared pilot is better,” says Rizai - a scared pilot is prepared to take more risks.

The guards, assuming a prison authority was arriving for a spot inspection, straightened their uniforms. As the chopper touched down in the exercise yard outside Wing E, the downwash from its rotors created a thick brown dust storm.

The pilot screamed:

They’ve got grenades! They’ve got explosives!”

Over the high-pitched roar of the turbine, a guard yelled: “Breakout! Breakout!” The escape was on.

Moments after Vassilis Paleokostas and Rizai ran to the chopper, it lifted off. The guards pointed their guns in the air but knew better than to shoot.

The prison is located on a residential street lined with orange trees, and children were kicking a ball against the prison walls. Rizai explains:

The ultimate aim in a jailbreak is to leave nice and pretty, and to say, ‘Cheers’ and ‘Bravo’ as you leave!”

At Skisto, north of Athens, the helicopter touched down in a quiet cemetery. “We made it,” exclaimed Vassilis, embracing his brother.

He gave the panicked pilot a string of worry beads to calm his nerves and booted away the kickstand of a stolen motorcycle. Rizai did the same. With a turn of the wrist, two bikes roared to life, and Paleokostas and Rizai were on their way north, on the long road to freedom. They were still wearing their prison clothes.

On a Sunday evening, Trikala police station was always empty. But that night Dimitrios Gravanis was toiling away on a big case. When the station’s telex machine whirred to life, Gravanis tore off the report.

He looked out of his window, and laughed. The statement from the Ministry of Public Order read: “We believed we were very close to Nikos Paleokostas. But it seems that, actually, he was closer to us.”

Inspiration behind bars

It is a four-hour drive south from Trikala to Korydallos prison. Whizzing through the streets of Athens in 2014, the country’s economic problems are not visible to the eye.

In the centre, Syntagma Square is bustling with iPhone users and McFrappe drinkers. But at night, some Athenians are forced to burn wood for fuel, sending a poisonous smog high above the Parthenon.

The air inside Korydallos prison is even thicker, full of cigarette smoke, bleach and anxiety. The prisoners in the sick bay have been on hunger strike. Officials warn that Greece’s overstretched prisons could explode in violence at any time.

“It's a system that is collapsing,” admits Spyros Karakitsos, head of the Greek Federation of Prison Employees.

I'm told I am the first journalist to be allowed inside and I have been warned that I am an attractive hostage target.

The Warden’s office is deep inside the psychiatric ward of the jail, and the walls are painted a sickly yellow. Framed slogans in Greek read: “You don’t have to be mad to work here, but it helps.”

The Warden pulls in a “witness” for our interview. He introduces a smart gentleman with tidy salt-and-pepper hair, dressed in grey Nike tracksuit bottoms and a blue jacket, who plays with worry beads as we talk.

“I’ve had all the robbers of the Plain [of Attica] in here, even Costas Samaras, the Artist,” the Warden boasts. He sighs:

The Artist was very clever. I remember once he made some wooden pistols in woodwork class, to try to escape. They were so real, you could load them!”

By my side, the gentleman stops clacking his worry beads and mumbles something to the warden. The Warden continues:

Batteries. The Artist took the plastic covers off two batteries, and loaded them in the chambers. When poked in a guard’s face, they would look just like two bullets!”

The Warden explains that he was off-duty at the time of the helicopter escape, and that the Artist was most likely the inspiration behind the plot. He shared Paleokostas’s obsession with videos, collecting in his cell a complete encyclopedia of prison films from Escape to Victory to The Shawshank Redemption.

I ask about the Artist’s involvement in the planning of the helicopter plot, for it seems like something ripped straight from his sketchbook. The Warden leans back on his chair, laces his fingers behind his head, and looks very pleased with himself:

You can ask him yourself. The Artist is sitting right next to you.”

By my side, Robin Hood’s partner in crime smiles politely and grants a rare interview.

When asked if Paleokostas really is a Robin Hood character, the Artist is unequivocal: “Yes, he and his brother would stop the car and hand robbery money to immigrants in the street. As we were driving the getaway car [from Kalambaka], we heard on the radio that we left 90 million behind!” he recalls. “Vassilis joked, ‘Shall we go back?’”

He speaks proudly of his former protege.

I was his mentor. I taught him how to drive a car, ride a bike, shoot a gun... and rob a bank.”

“And what inspired your crime spree?”

“Movies.”

Before I am escorted out of the jail, the Artist shakes my hand and boasts of his forthcoming exhibition of paintings.

“Check me out on Facebook!” he says, cheerily.

On the run

After the prison escape in 2006, Alket Rizai and Nikos Paleokostas were quickly captured, but Vassilis vowed to continue his crime spree.

On 9 June 2008, he kidnapped George Mylonas, a billionaire aluminium magnate who had outraged the nation’s poor by claiming that “workers need to tighten their belts”.

But Mylonas said of his captors: “They were polite, and they treated me well.” Paleokostas even bought him a morning newspaper every day and cheerily asked him, “What’s going on, Georgi?” - before letting him drive home in a stolen BMW.

The reported ransom was 12 million euros.

Eventually, Greek authorities traced Paleokostas back to the house where Mylonas had been held. There, on 2 August 2008, as the fugitive was pouring a cup of moonshine and settling down to watch a DVD, a SWAT team smashed through the door.

Police found a DVD copy of Ransom, and the Al Pacino movie Heat - about two veteran bank robbers evading the cops.

He had been on the run just 791 days when he was captured, and the police were jubilant.

“The relatively rapid capture of Vassilis Paleokostas, one of Greece's most notorious criminals, is a much needed boost to the morale and public image of the Greek police,” read an official wire sent from the US Consul in Thessaloniki to the Secretary of State in Washington, later made public by Wikileaks.

Malcolm Brabant, then the BBC’s Greece correspondent reported:

For the first time in nearly two decades, the Greek police have obtained the last laugh in their long-running battle of wits with the notorious Paleokostas brothers.”

It is not known how Paleokostas spent those ransom millions, but at his pretrial hearing in Athens in January 2009, on new charges of kidnapping and robbery, a mob gathered outside the court.

Farmers, peasants and anarchists alike, all chanted:

Death to pigs! Freedom to Paleokostas!”

A group of young women invaded the courtroom, acting like a “fan club” of “teenage girls close to their musical idol”, in the words of the tabloid weekly, Espresso.

Around the same time, Alket Rizai’s glamorous girlfriend, Soula Mitropia, also became a courtroom sensation.

As Rizai returned to court to be sentenced to 25 years, she theatrically sobbed and threw her arms around him. And when no-one was watching, she slipped a mysterious watch into his pocket.

The judge sent Paleokostas back to his old cell at Korydallos, along with Alket Rizai, to await his verdict. The bandit, defeated, told the court:

I played and lost. The police are victorious.”

On the streets of Athens, anarchists mourned the end of his remarkable winning streak.

In Greek drama there is a device known as peripeteia, when the plot takes an abrupt turn, and a character’s circumstances suddenly change. Aristotle wrote that it was one of the most powerful moments of the play.

And what happened on 22 February 2009 would make Vassilis Paleokostas infamous around the world.

It would lead to the creation of a Facebook fan page with 50,000 members, and inspire a folk song:

Vassilis is untouchable and in his methods of escape undefeatable Vassilis, you are uncatchable.”

Second flight

To the guards watching on security cameras, the morning looked like any other.

Paleokostas pumped a little iron in the prison gym, and jogged around the exercise yard, while Rizai picked winners on the Propo betting game. Rizai recalls:

I’m the kind of person who has intuition. I feel things, when there’s something good that’s about to happen, I can feel it.”

At 15:00 Mitropia telephoned him on the mobile-phone wristwatch she had slipped into his pocket in court.

It was time.

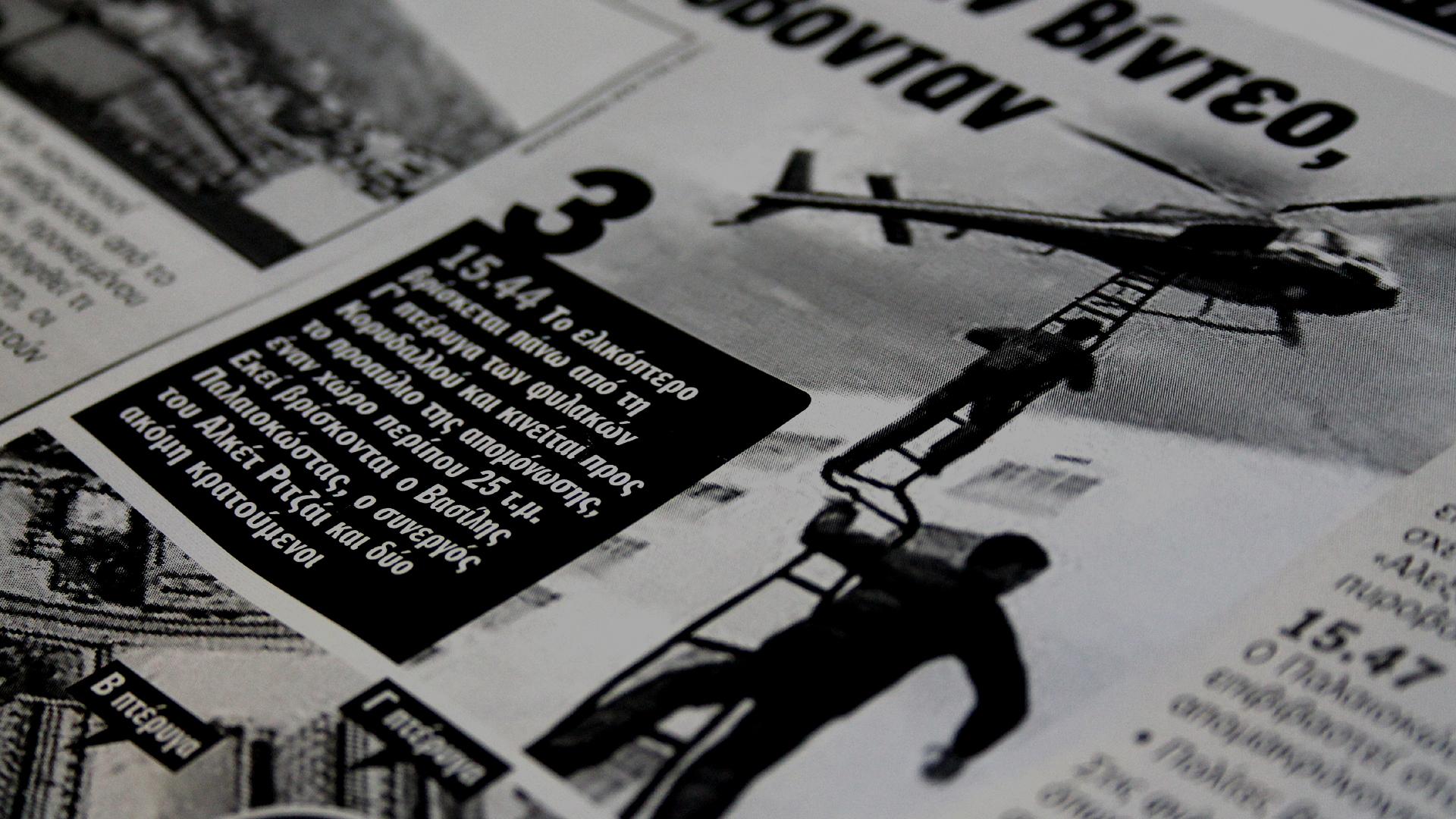

The emergency siren at Korydallos prison wailed like a sad violin as the guards ordered the convicts in from the yard. It was 15:45 on the day before Paleokostas’s trial was due to start.

High above them, a guard on a lookout tower sensed the unmistakable hum of rotor blades. When a chopper descended over the third wing, the guard grabbed his automatic weapon and sounded the alarm.

This was not a drill. And this time they would shoot to kill.

The helicopter was a hijacked rental from the company Interjet, famous for promising its customers “clever escapes”. A glamorous “Mrs Alexandrova” had boarded the AS355N chopper at Athens’ airport. Pulling a hand grenade from her handbag, she told the pilot:

We’re going to pick up the kids. Korydallos prison, or you die.”

Brandishing a machine gun as the helicopter hovered over the prison, she threw a rope ladder down to Rizai and Paleokostas. That woman, it’s alleged, was Mitropia.

A desperate guard lunged for the escaping inmates, but the Albanian pulled out a kebab skewer and warned him: “Step back or I’ll stick you!”

“Let’s go!” Paleokostas yelled, and the pilot pulled the lever for maximum power and rose into the air. Below them the prison sounded like a soccer crowd, convicts cheering and shouting.

But as soon as the helicopter door closed, three guards grabbed their MP5 submachine guns and opened fire, unleashing 30-round clips into the belly of the aircraft.

One bullet found the gas tank, and another severed a fuel line. Aviation fuel sprayed into the cockpit as the pilot whispered a prayer.

Simultaneously, a woman in a nearby apartment used a video camera to record a Greek YouTube hit.

“Again, we made it,” exulted Paleokostas. “And even though they shot at us, we did not shoot anyone.” But the fuel needle was falling, forcing the helicopter to make an emergency landing.

Back in Trikala, Detective Gravanis read the news of a second escape on the police telex system. “I couldn’t help but laugh,” he says.

Television soap operas across Greece were interrupted with news of the escape. For the second time, a nation was gripped by the adventures of Vassilis Paleokostas.

Paleokostas, Rizai and Mitropia went on the run together.

One night, in a village near Koziakas, outside Trikala, a stranger knocked on the door of an impoverished family. The father had serious health problems, and was too poor to pay for treatment.

An envelope was tossed into the house containing 10,000 euros, and the man vanished into the night.

But the police were closing in. Paleokostas complained in a letter sent to the media:

There were thousands of policemen wherever I turned my eye, not to mention the undercover ones.”

“Dozens of headhunters that prowl the mountains… armed to the teeth with survivor-style weaponry, and a menacing, numb look in their eyes.”

According to intelligence, the fugitive had developed “a weakness” for the Volkswagen Touareg for its off-road abilities, and stole them frequently, traversing highways and mountains with ease.

On his stereo, he liked to hear finger-picking Greek guitar music, as he outran the cops and continued his crime spree.

Hunt for a fugitive

For the past 20 years the CIA has operated a secret anti-terror squad in Athens. They are known as The Invisibles, a crack team of 15 Greek and American intelligence officers tasked with smoking out terrorists and “special case criminals”.

In 2009, Vassilis Paleokostas became their number one target.

From a fake business address near the five-star Divani Caravel Hotel in central Athens, the Invisibles helped the Greek police close the net, with American cash footing the bill. His days were surely numbered.

On 31 March 2009, at 14:03, there was a highly unusual bank robbery in Trikala, Paleokostas’s home town. Three robbers - two men and one woman - burst into the Alpha Bank. Armed with pistols and a short-barrelled shotgun, the robbers wore tights over their faces and motorcycle helmets as they yelled: "Robbery! All hands up!"

The unlikely trio held up seven employees and 15 customers, emptying the safe of 250,000 euros, before fleeing on three stolen motorbikes.

In a news report headlined “Robbery… with perfume!” one Greek newspaper reported that police were considering the robbers to be “the fugitive Vassilis Paleokostas, Alket Rizai and their female accomplice, a ‘blonde Lara Croft’.”

Shortly afterwards, Rizai and his girlfriend were arrested. Mitropia was convicted of hijacking the helicopter, and accused of being the mysterious blonde with the machine gun in the helicopter – though she still fiercely denies it was her.

Yet Paleokostas continues to evade the Invisibles. Epic manhunts have seen heavily armed cops scour the countryside with heat-seeking helicopters, flying over the mountains where Vassilis rustled cattle as a child, and where families of peasants still eke out an existence from the rocky soil.

Five years since his dramatic escape, Vassilis Paleokostas, now 48, remains on the run, and the bank heists persist.

Only once has his hiding place been compromised - when he tried to rent movies from a local video store.

On 14 April 2009 at 20:00, a team of 15 undercover police in three unmarked cars chased him along the coastal road of Alepohori in southern Greece.

Cornering the fugitive, they pointed their automatic weapons at him and prepared to shoot. “So I let it rip,” wrote Paleokostas in his open letter to the media:

I sped down an alley to escape, and bullets were dancing inside my car’s cabin. These guys opened fire and shot more than 150 bullets in 15 seconds.”

By contrast, he said, in all his years as a robber and a fugitive, he had never fired a gun at a human. He signed off the letter with a clear fingerprint in blue ink.

A few months after he sent the letter, on 24 June 2010, the authorities say they found Paleokostas’s fingerprint on a letter bomb sent to assassinate Public Order Minister Michalis Chrysochoidis.

It exploded in the hands of his aide George Vassilakis, 52, killing him instantly. Paleokostas was quickly branded a terrorist and a killer, with a 1.4-million-euro bounty placed on his head.

His supporters, such as George Ras, 23, from the Athens suburb of Exarcheia, smelled a set-up:

How do you find a fingerprint on a bomb that destroyed a man, and blew down walls?”

Since the financial crisis in 2010, and the riots, hardship and unemployment that have followed, the ranks of anarchists and militant anti-capitalists have swelled. Exarcheia is their stronghold, and pro-Paleokostas posters and graffiti on its walls emphasise the local support for his raids on the banks.

The bandit has become a symbol of a troubled time, like John Dillinger during America’s Great Depression, or Jesse James during the outbreak of the US Civil War in 1861.

Late last year, police believed they had Paleokostas cornered again inside a farm in the mountain regions of Kozani, some way north of Trikala.

After a full-scale search of the property, all that was found were banknotes with serial numbers matching his ransoms and bank robberies, suggesting that he is very much at large today, doling out gifts to farmers.

Rumours in the villages say Paleokostas has a foreign girlfriend, and a newborn baby boy. Everyone in Greece has a theory about where he lives today, and, like a Greek Elvis, there are regular “sightings”.

Many Greeks believe the outlaw is protected by monks, living in the mountain monasteries that sit like fairytale castles on those snow-capped peaks.

In October 2010, during the last robbery spree, a man resembling Paleokostas was spotted on surveillance cameras at a petrol station. If it was him, it would appear that he’d had plastic surgery.

Wigs and makeup found in one hideout suggest Vassilis could even transform himself into a woman, at a pinch.

The press have recently started calling him The Phantom, while locals just call him King of the Mountains.

The petrol station footage was shown to me in a cafe in Trikala by Dimitrios Gravanis, the retired detective. He told me:

I will never stop looking for Vassilis. It’s not a matter of if he strikes again, it’s when.”