The lonely death of Delhi's jungle prince

- Published

In terms of snobbery it was hard to beat the man who claimed to be the last prince of the royal house of Oudh.

"Don't talk to me about the Mughals," Prince Cyrus once bellowed at a friend of mine. "They were as common as dirt."

The Mughals, of course, were the rulers of India from the early 16th Century until the British violently overthrew them in the mid-19th Century. They were, without question, one of the grandest and most powerful imperial families in history.

But Prince Cyrus insisted his lineage was even more noble, despite the fact that he now lived in abject poverty.

There are no doors or windows, just open arches

The prince was very much a product of his formidably eccentric mother. She called herself Begum Wilayat Mahal and claimed to be the direct heir to the kings of Oudh, whose realm covered much of what is now Uttar Pradesh, India's most populous state.

The family had huge estates and vast palaces, and hosted famously lavish parties. The British regarded them as unacceptably dissolute. A contemporary report describes how the last Nawab of Oudh had resigned himself to a life of "debauchery, dissipation and low pursuits". He was unceremoniously booted off his throne in 1856.

The family lost their fortune but not their sense of entitlement and, in the 1970s, the Begum decided to take action. She camped herself in the First Class Waiting Room of the Delhi railway station together with her young son and daughter, seven liveried Nepali servants, some 15 ferocious bloodhounds, and a collection of huge and beautiful Persian carpets.

And there she insisted she and her retinue would stay until the Indian government recognised the sacrifice she claimed her family had made during the uprising against the British in 1857.

Cyrus's mother called herself Begum Wilayat Mahal

She cut an imperious figure: square-jawed, stern-faced and utterly implacable. I met an eminent MP this week who recalled how she had set her dogs on him when, as a young boy, he'd had the temerity to approach her.

After eight years, the government finally capitulated and offered her a home in the deceptively grandly named Malcha Mahal. "Mahal" may mean palace in Hindi but this is actually a thoroughly overgrown medieval hunting lodge, deep in what is known as the Ridge Forest, a swathe of dense woodland that - rather unexpectedly - bisects the teeming megacity that is Delhi.

The place has no electricity or running water, no doors or windows, just a series of large open arches. Nevertheless the Begum decided to stay.

She hung a metal sign outside: "Entry restricted. Cautious of hound dogs. Proclamation: Intruders shall be gundown." And there, what remained of the house of Oudh lived in regal isolation as the keekar and babul trees grew up around their ancient new home.

The ruins of the medieval lodge are hidden in the forest

Until, that is, the princess succumbed to years of depression and took her own life by - or so the story goes - grinding her remaining diamonds into dust and swallowing them.

True or not it certainly created a legend that drew foreign correspondents towards the remaining members of the family like a moth towards a candle flame.

Which is where I come in.

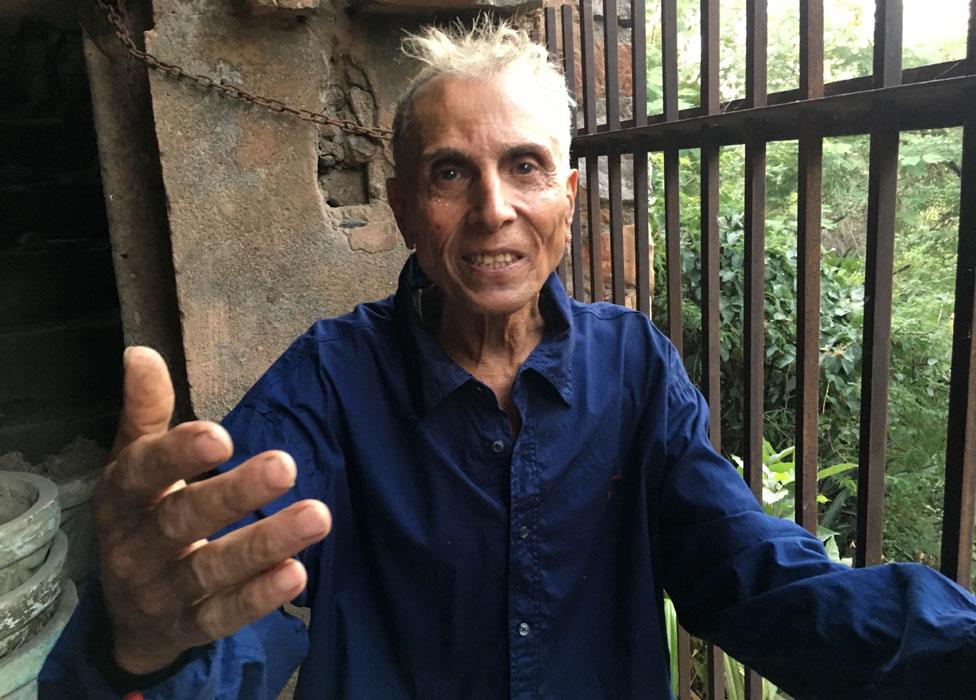

Prince Cyrus with Will Rowlatt

I felt distinctly uneasy as I led my six-year-old boy past the now rusted but still ominous warning sign and into the undergrowth. I knew Prince Cyrus and his sister Princess Sakina were famously unfriendly and had calculated that bringing my tousle haired son along might make them a little more welcoming.

A rough path lead up a small hill, and then the formidable walls of the lodge appeared. I was relieved there was no barking - the bloodhounds seemed to have vanished.

Prince Cyrus was initially angry at our intrusion when he appeared at one of the arches, but Will's charms and the power of the BBC brand swiftly won him over.

Find out more

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service, or on Radio 4 on Thursdays at 11:00 and Saturdays at 11:30 BST

Soon I was making regular visits. Prince Cyrus would complain about the rain that seeped through the roof, the spiders, and the jackals that howled in the woods at night. But most of all he would talk about terrible sorrows his family had endured and all the injustices they had suffered over the years.

I learned that Princess Sakina had died some months before my first visit and that Cyrus was now alone in the crumbling lodge.

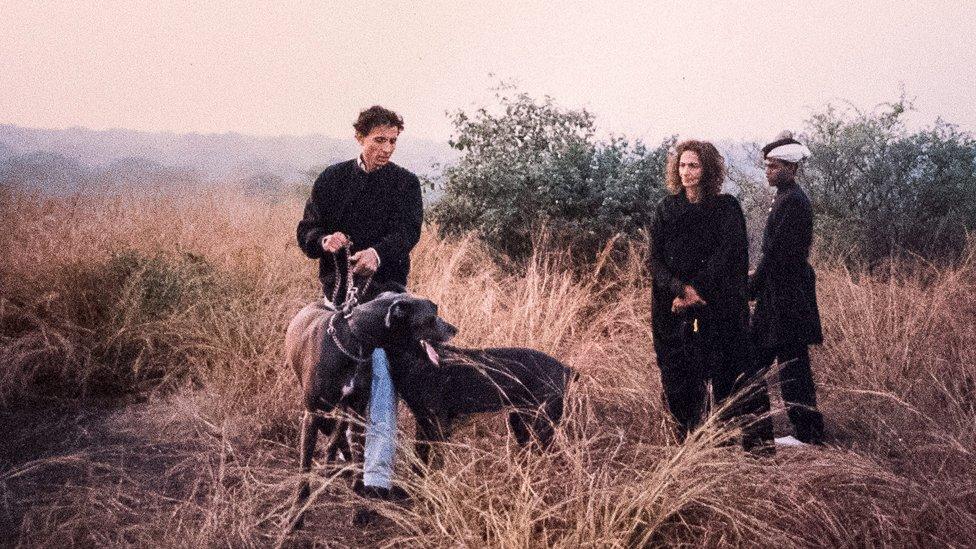

Prince Cyrus with his sister Princess Sakina and their dogs

He showed me the table setting he still laid for his mother, and told me how he refilled her glass with fresh water every morning.

It was clear that he was terribly lonely yet his unshakable belief in his own nobility prevented him from mixing with anyone he regarded as a social inferior - and that meant virtually everyone else on Earth.

As far as I could tell, his only other regular visitor was the bureau chief of the New York Times.

She left Delhi in July. I was also out of the city for virtually the entire summer. So neither of us had seen Prince Cyrus for a few months when I hiked up to the Mahal last week.

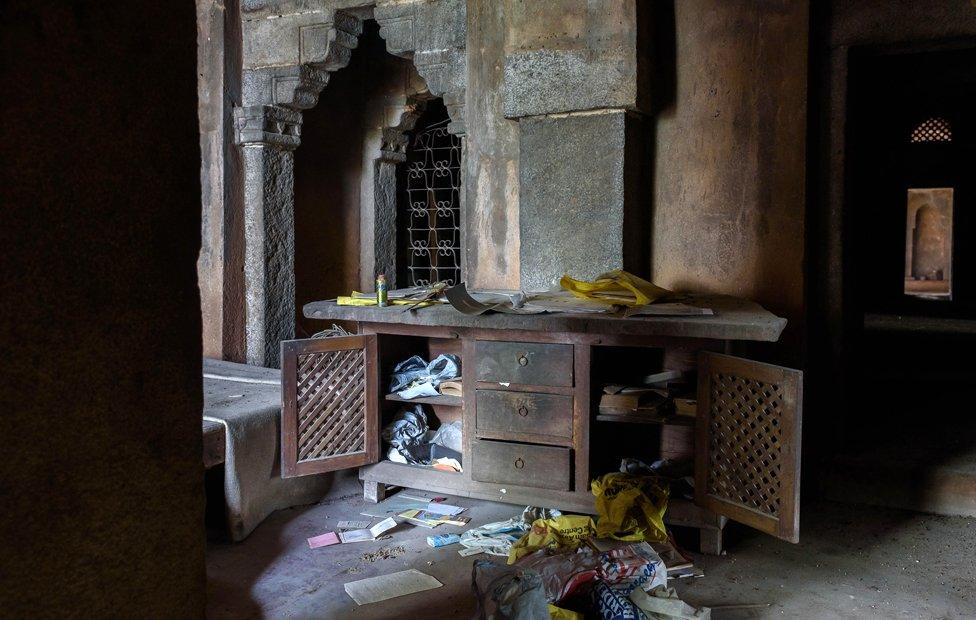

Prince Cyrus' home was ransacked after his death

The lodge was silent when I called his name. His mother's place at the table was set but there was a smudge of green algae in the water. His belongings had been ransacked. On the floor was a litter of letters and business cards - all of them from journalists.

It turned out his body had been found by the police a month earlier.

Prince Cyrus still set a place for his mother at table, even after her death

In death as in life, the prince had never betrayed his family's belief in their own exceptional nature.

"Ordinariness is not just a crime, it is a sin," Cyrus's sister Sakina had once declared to a colleague: "A sin."

There was certainly nothing ordinary about Cyrus or his family. That was both their charm, and their tragedy.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.