Colin Thubron returns to Damascus after 50 years

- Published

It is 50 years since writer Colin Thubron published his portrait of Damascus, in which he recounted his travels around the Syrian capital and explored the history of the city. A lot has happened since then - not least the civil war. Recently Thubron returned to Syria to see what was left of the place he recalled so fondly.

The city that comes into view is of course bigger than I remember - its population must have quadrupled. Since I was here its suburbs have swamped the Old City that I loved, and even inside its walls a rash of restaurants and boutique hotels has appeared.

But they're all closed now, or empty. It's a city at war. Whole streets are fenced off by tank blocks and razor wire. Less than a mile away from my empty hotel I can see burnt-out tenements still in rebel hands.

This is perhaps the oldest continuously inhabited city on earth. In the Muslim world it had grown open and tolerant. A quarter of its people belong to Christian and other minorities, including Alawites, a sub-sect of the Shia, who dominate the government and army. However reluctantly, the Damascenes cling to the regime of Bashar al-Assad. The Islamist alternative, just outside the walls, might be fatal to them.

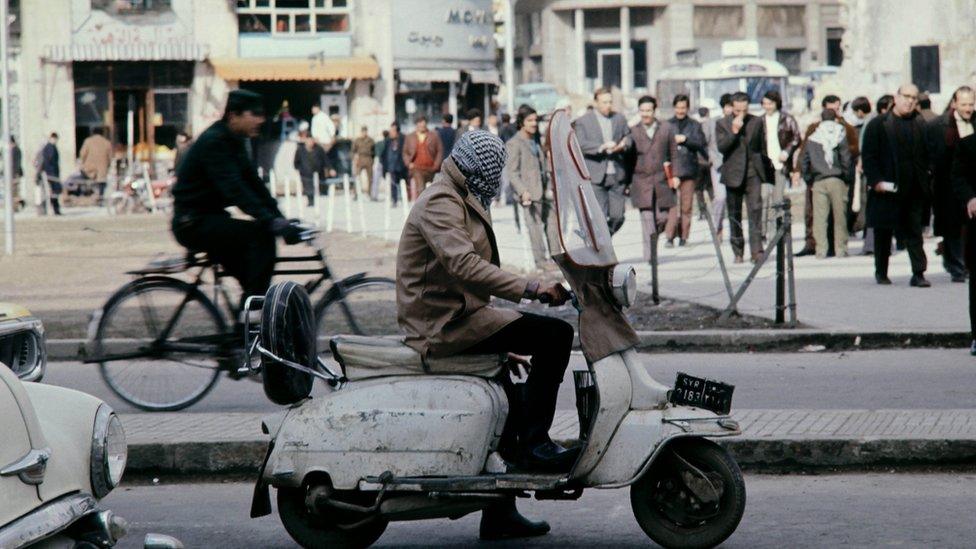

Damascus in the early 70s, not long after Thubron's book about the city was published

Fifty years ago I was almost alone here, because tourists hadn't yet come. Now I'm alone because they're gone. Yet I see an Old City miraculously intact. It's escaped the devastation of Aleppo.

But late every night the regime's artillery opens up on the enemy suburbs. It sounds like far-off thunder. In the dark I stand outside my hotel, listening, wondering how this can continue. Once a week a defiant mortar-shell flies the other way.

By day I wander the alleys and monuments that had so fascinated me as a young man. Sometimes I find myself gazing through his eyes, remembering the youthful enchantment of entering an old mosque or a sultan's tomb.

Shoppers in a Damascus market in the early 70s

I'm more wary now, and old. The sentries rarely frisk me. In the great bazaars, still bustling, the shopkeepers stare at me with hope, as if I might be the vanguard of returning foreign business.

I'm surrounded by ethnic complexity. I glimpse russet hair, and green or hazel eyes. But there's a darker and more homogeneous influx - rural immigrants, refugees.

In the lanes of the Old City an odd quiet descends. I think it was always like this. But now there are more windows boarded up, more doors padlocked. Behind them, out of sight, I know, are marble-paved courtyards, fountains, lemon trees. I find the home of a student I once knew, but I can see through the windows that it is derelict, the courtyard piled with builders' rubble.

I check to ensure that I'm not being followed. People speak with me more cautiously than they did. Once I could barely walk down a street without an invitation to coffee (from Christians) or tea (from Muslims). But those voices have gone.

"We can't see an end to it," people say now. "We've become like Baghdad or Kabul or Tripoli. This war will never end. And prices go up all the time."

Find out more

Colin Thubron

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service, or on Radio 4 on Thursdays at 11:00 and Saturdays at 11:30 BST

They talk of suicide bombs, of children killed, houses wrecked. But the deepest wounds, I think, are in people's psyches. They seem to be losing hope. There is a sweetness of old custom still, and hospitality. If I linger long enough at a door or enquire strenuously for an absent family, somebody probably will ask me in. "But Syria's just the toy of foreign powers," they routinely say. "Here, have some coffee, you are our guest… But Syria is bleeding."

My friends may have gone, but the buildings I loved are still here. The only damage I find is to the mausoleum of a warrior sultan against the Crusaders, which has taken a mortar bomb through its dome.

Then I come with trepidation on the city's greatest monument - the 8th-Century Ommayad Mosque.

The first great mosque in Islam, it was built in the shell of a Roman temple to Jupiter. Its sister mosque in Aleppo was wrecked months ago. I find the huge spaces still unblemished. A shrine contains the supposed head of John the Baptist. Worshippers are caressing its gilded bars, Muslims and Christians venerating it together.

Above all, the mosaics in the courtyard arcades still shine undamaged. They're beautiful things, in emerald green and gold. In the absence of any living figure portrayed, they depict an idyllic river flowing among palaces lit with mother-of-pearl lanterns - an image of the Barada perhaps, the river that feeds Damascus, or a foretaste of the Koranic paradise.

The head of Syria is Damascus, reads the biblical Book of Isaiah, and Damascus is still the head of Syria. But it's a different Syria, and a tense city. Its gates and railings are plastered with outsize photos of soldier-martyrs, and the bazaars hung with portraits of Bashar al-Assad, who looks justifiably a bit concerned. His notional Shia faith elicits Iranian support.

"You see these people everywhere nowadays," a man complains to me. "The Shia are walking tall now…"

And now I start to see them too. Iraqis and Iranians, mainly, praying at the supposed tombs of Mahomet's family. They clutch at the barred cenotaph that separates them from the buried head of their martyred Imam Hussein, and trail through the Bab al-Saghir cemetery just outside the city walls. I come here too. More than 40 pilgrims to its shrines were killed by bombs, and now the graveyard's patrolled by heavily-armed soldiers.

Here Mahomet's muezzin Bilal, the first man to summon the faithful to prayer, is buried in a little green-domed tomb. And suddenly at noon the call to prayer arises, whose plangent cadence, relayed from minaret to minaret, had entranced me all those years ago. But now its cry of "Allahu Akbar" resonates differently among the gravestones, and I wish I could love the sounds as I once did.

It's not the army that controls this country, I think, but the Mukhabarat, the feared intelligence service. I was taking a careless snapshot of the city from a hillside suburb when two plainclothes men appeared behind me. They escorted me to a room immured among poor houses. There my captors multiplied to five, and were deferential at first. They spoke formulaic English, and my tourist Arabic had gone. You are our guest, you have nothing to fear. What are you doing here? How did you get here?

I answer that my visa was granted by their Ministry of Information.

They demand my passport and camera. The passport bears an entry stamp from the Syrian frontier with Lebanon. The camera they scroll through avidly. It shows photos of Damascus alleys, of posters stuck to the city gates - martyrs, slogans. Their suspicion grows. They scroll back to leftover photos of a holiday on Lundy Island in the Bristol Channel. There's a shot of a pretty woman in headphones in the cockpit of a helicopter.

"Who is this?"

"This is my wife."

"What she doing in airplane? Why has she these on her ears?"

"These are headphones. She is going to Lundy Island."

"She listening to MTN or Syriatel?" These are Syrian network providers.

"No. There is no Syriatel on Lundy Island. She is listening to the pilot."

They stare harder, their suspicion fomented. They scroll back to shots of Highland cattle and seals gazing at the camera from the sea.

"What are these?"

"These are seals."

"Why are they looking?"

But now they have summoned a fox-faced officer who looks senior. I'm driven to a guarded compound deep in the city. A thin, tiled stairway leads into a warren of sordid passageways. There's little light and an acrid smell I can't identify.

I'm put in a prison cell, but the iron door is left open and it's lined with filing cabinets. Three different portraits of Bashar al-Assad hang on the walls, festooned with tinsel. I am afraid now. The questioning grows more intense. I have the telephone number of the Ministry of Information official who granted my visa, but nobody rings it. A thug in a black vest lumbers in and out, as if mutely playing bad cop, while different interrogators come and go.

At last I'm taken to a huge room where a uniformed officer sits at a desk with his back to the light. There's no more talk of Lundy Island or seals. "I have just returned to a city I once loved," I say, as if to emphasise the sadness between that time and this. He lays my passport and the camera on his desk, within reach. "I think these are holiday snaps," he says. But it is only an hour later that I am free, after Fox-face drives me to the Ministry of Information, where my official - an elegant woman behind another huge desk - describes it all as a misunderstanding.

Further reading

Zahed Tajeddin had always wanted to live in Aleppo's historic old town, in one of the city's ancient houses, with a front door opening into a corridor that leads to courtyard with a fountain and jasmine climbing up the walls. As a teenager he would explore the old houses just before they were demolished, scampering through courtyards and over crumbling rooftops. He finally managed to buy one for himself, after making a career as a sculptor and archaeologist, in 2004.

Return to Aleppo: The story of my home during the war

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and Twitter.