Returning to Kashmir, where our parents were shot in front of us

- Published

Seventy years ago, a young British couple was shot dead at a mission hospital in Kashmir, making orphans of their three sons - one only two weeks old. To mark the anniversary two of those sons, now white-haired, made a personal pilgrimage to the spot.

"I feel very emotional to be here," says Doug Dykes, standing yards from the veranda where his mother and father suffered fatal bullet wounds when he was two years old.

"I saw my parents being killed - that's what I've been told. My father tried to stop the attackers approaching the nuns and he was shot. I ran screaming towards my father. My mother ran after me - and then she was also shot."

There's a touch of anguish in his recollections - a sense that he may in some way have been responsible for the death of his mother.

James (left) and Doug Dykes at the graveside

We are standing by his parents' graves in this remote corner of the Kashmir valley, the headstones shaded by recently harvested apple and walnut trees.

It may seem like a tranquil spot, but Tom and Biddy Dykes, an army officer and his wife, were killed in the opening salvos of the Kashmir crisis - and 70 years later the conflict continues to claim lives just about every day.

In all, six people lost their lives at St Joseph's Catholic mission in the riverside town of Baramulla on that October morning in 1947. Jose Barretto, the husband of the hospital doctor, tried to save the nuns who ran the mission and was put up against a tree and shot. A nurse, Philomena, died seeking to protect the patients. Motia Devi Kapoor, a patient, was stabbed to death in her hospital bed.

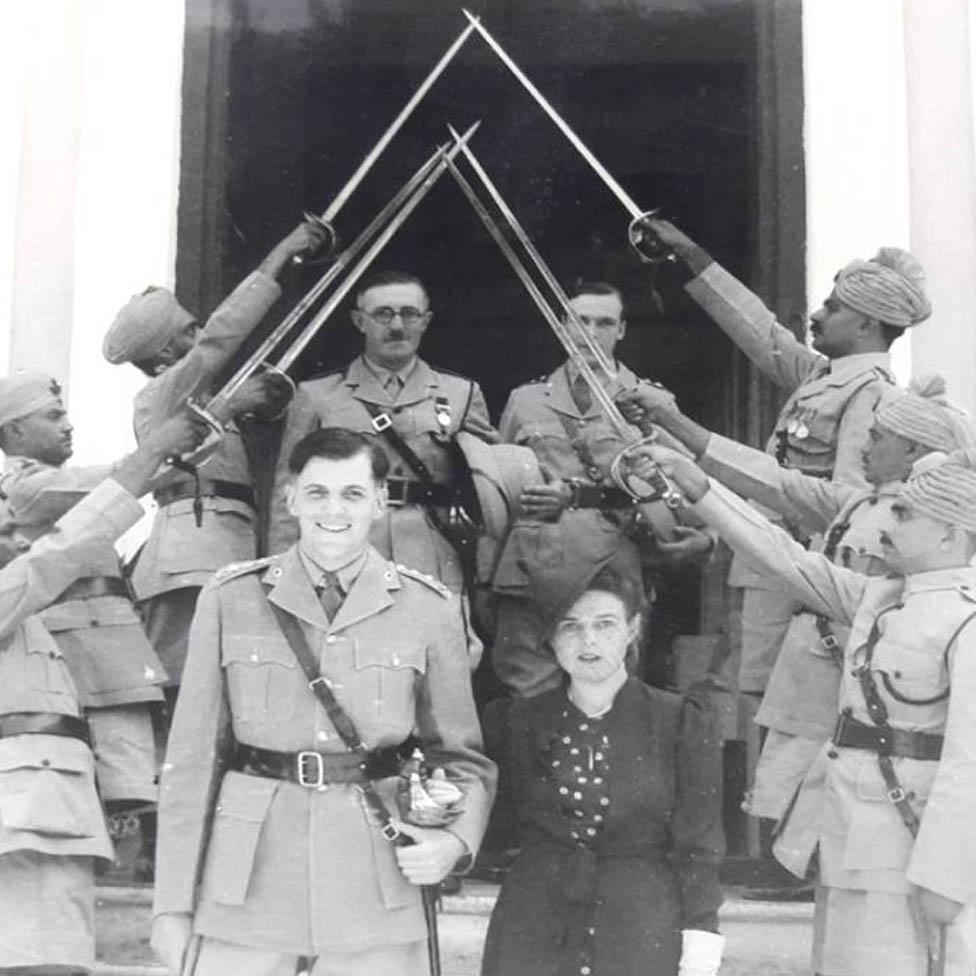

Tom and Biddy Dykes on their wedding day in 1940

The Franciscan Missionaries of Mary also lost one of their own - Sister Teresalina, a newly-arrived Spanish nun in her 20s. She leapt in front of the convent's Belgian mother superior, taking a bullet intended for the older woman. She is buried in the nuns' graveyard on the other side of the mission grounds.

All were murdered by armed tribesmen from Pakistan who invaded Kashmir to try to prevent the princely state becoming part of India after the British withdrawal - and to take away as much loot as they could carry. As they ransacked St Joseph's on 27 October 1947 the first Indian troops were landing in Kashmir to repulse the invaders - and they have been here ever since to prevent the region being seized by Pakistan, which claims it as its own.

Security concerns were the main reason why the oldest of the three Dykes children, named Tom like his father, never managed to revisit Baramulla before his death in 2003.

When I met him a few years earlier his recollections of the attack were extraordinarily vivid.

"I can remember waking up, and there was gunfire all around the place," he told me.

"Then these fellows that had raided the hospital started to batter down the door of the room we were in. The splinters started to fly across the room, and I could see the wild faces through the cracks in the door.

"The tribesmen were looting the place, they were pulling everything apart, and putting their booty into sheets which lay on the floor and were made up into bundles."

Biddy Dykes

A family servant managed to take the five-year-old away from the marauders. A little later they returned to see if they could find Tom's family.

"We went back to the central part of the hospital, a garden area with a path around it. And we came across these bodies, covered with blood. And sitting on top, howling his eyes out, was my little brother Douglas."

I stumbled on this story when, 20 years ago, I met the last remaining nun who had survived the ordeal. Sister Emilia, an Italian, recounted how the tribesmen had climbed over the mission walls, smashed through locked doors and manhandled some of the nuns. After they killed her friend - the new Spanish sister, Teresalina - Emilia thought she too was about to die.

Tom Dykes

The hospital run by the 16 nuns had a high reputation. Biddy Dykes - a motherly woman with a "round, happy face darkish hair and a lovely smile", in the description of another army wife - went there to give birth to at least two of her sons.

Their father was a Sandhurst-trained soldier from a family with a tradition of service in the British Indian army. He married Biddy, a military nurse, at Agra, the city of the Taj Mahal, in 1940, and had risen to the rank of lieutenant-colonel by the end of World War Two. When the British pulled out of India in August 1947, he agreed to stay on for a few months as an officer in the Indian army's Sikh Regiment to help the transition.

These armed Pakistani tribesmen were photographed in Rawalpindi en route to Kashmir, a few days after the attack on Baramulla

The family has an anguished letter Biddy Dykes wrote 10 days before she died, shortly after giving birth to her third son, James. The security situation was alarming and she was desperately waiting for her husband to turn up and get them out.

"Hells Bells, I'd give anything to see Tom walk in this evening," she wrote. "He said in one letter that he'd be up here today. But I don't think there is an earthly chance."

In fact, Dykes did make it to Baramulla but was unable to get his family to safety.

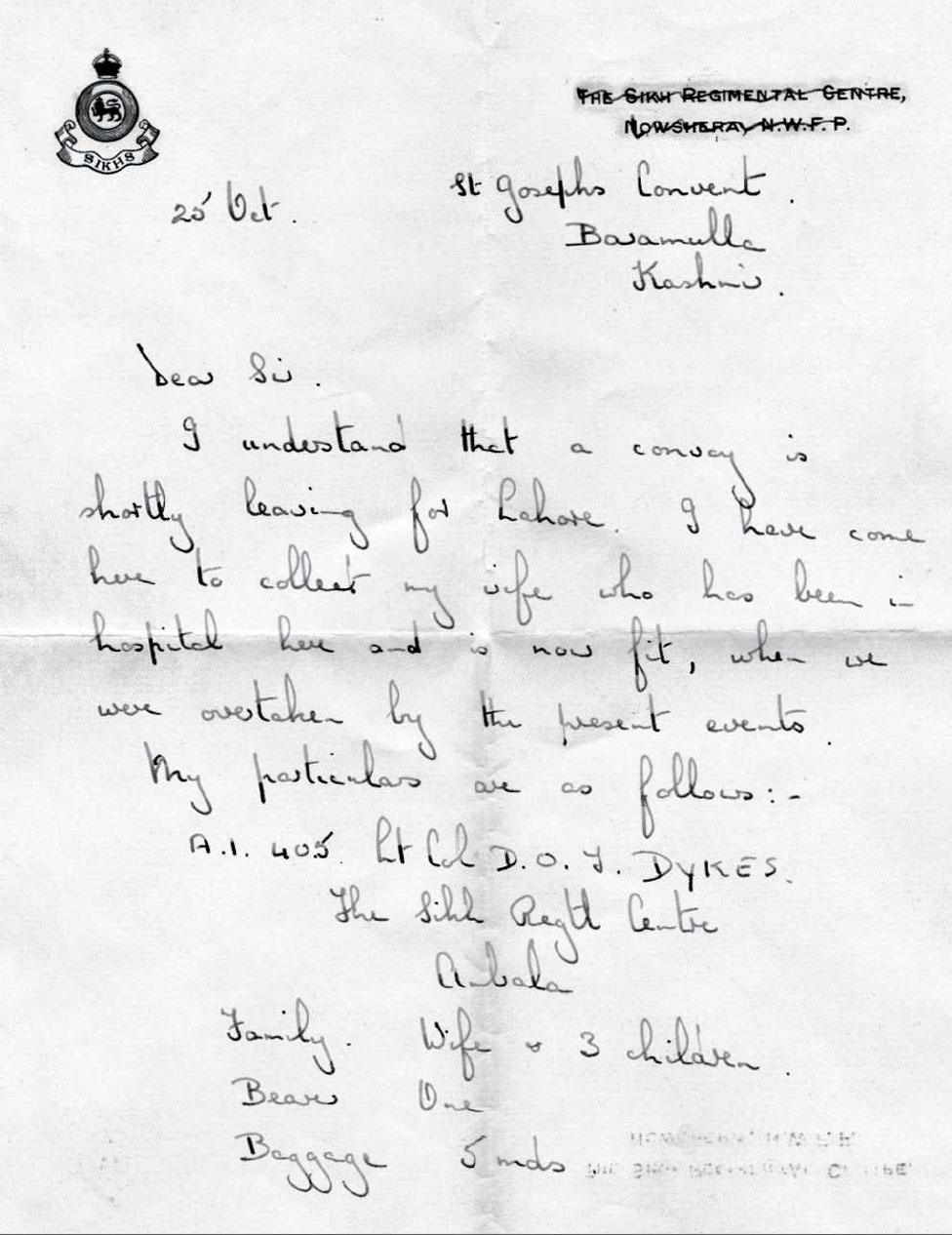

A letter has emerged that he wrote after his arrival to a British officer in the Kashmiri capital, Srinagar, just 30 miles away. In it he explains that he has come to collect his family only to be "overtaken by the present events", in his astonishingly understated words. In clipped military fashion, he writes: "I should be most grateful if you would send a vehicle here to Baramulla to collect us." With an invasion underway, the evacuation was impractical. Two days later, he and his wife were dead.

The three orphaned Dykes boys along with about 70 others were held captive in a single hospital ward for 10 days, while war raged around them. The Indian air force repeatedly bombed the mission, which the Pakistani invaders were using as a transport and supplies depot.

The two older boys eventually returned to Britain by boat. James, the baby, was so weak he was not expected to survive. He was initially cared for by Lady Messervy, the wife of the British general who had become the first commander-in-chief of the Pakistan army, and slowly began to improve. When, a few months later, he was well enough to make the journey home, he was taken in by a different wing of the family. He didn't see a lot of his older brothers as they were growing up and at 18 he emigrated to South Africa.

Letter from Col Tom Dykes (courtesy of Fiona Shipley)

"We never talked much about our parents - we knew the bare facts of what happened, but we were encouraged not to dwell on it," says Doug Dykes, a brewer by profession who lives in Dorking, just outside London. It was only when I made contact with the family, sent photos of the graves and sought their testimony, that the brothers started to talk among themselves about their memories and feelings, he tells me.

St Joseph's lies at the western end of Indian-administered Kashmir, where the mountains start to close in on the valley. The road from the Kashmiri capital, Srinagar, is lined by Indian army bases and choked with the incessant movement of the huge numbers of troops deployed to ensure that neither Pakistan nor Kashmiri separatists prise the region from Indian control.

Today there are 13 nuns at St Joseph's, all Indian - though none Kashmiri. In 1947 all except one were from Europe. As well as the small hospital - now, as then, specialising in maternal and women's health - they run a nursing institute which is currently training 67 local Kashmiri girls. The nuns recount how at times in recent years, as the security situation worsened, they have been encouraged to pull out of Baramulla. But they have insisted on staying. The service they provide to the local community is clearly appreciated, as is the evident compassion with which they conduct their mission.

For the 70th anniversary of the killings, the nuns took it on themselves to organise a memorial mass, candle-bearing processions and the laying of wreaths to honour those who lost their lives. They invited the two surviving Dykes children to attend and asked if I would come along too.

The army has spruced up the graves for the occasion - a touch of whitewash, a few additional pot plants and camouflage sheets to protect those gathering around the graves. The quiet of the occasion is broken by the whirr of an army surveillance drone overhead, keeping an eye out for intruders.

Col Dykes lies in the only Commonwealth war grave in Kashmir, and the top-ranking Indian general in the area places a wreath, as does the diocesan bishop and the provincial head of the nuns' order. The Dykes sons both lay wreaths too - Doug makes a point of honouring his mother.

For Doug and James Dykes, the warmth of the welcome from the nuns and the poignancy of the ceremonies is overpowering.

James, who stayed in South Africa and made a career as a tax consultant, is able to visit the room where his mother gave birth to him, as well as seeing the spot his parents were buried just two weeks later.

"I'm gobsmacked by it all. I just can't find the words," he says.

"I never expected to make it here."

Neither of the surviving brothers can be sure to make it to Kashmir again. It was a precious chance - possibly a last chance - to get close to the young couple who died here, and whom they have thought about all their lives.

Andrew Whitehead, a former BBC India correspondent, is the author of A Mission in Kashmir.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.