Why some Germans look at Syrian refugees and see themselves

- Published

Christa Nolte as a baby with her mother and her brother - she still has the teddy bear

Between 1944 and 1947, an estimated 12 million ethnic Germans fled or were expelled from their homes. Overshadowed by the crimes of the Nazis, their stories have often received little international attention. But these days, as Bethany Bell reports from Germany, the new arrivals from Syria have awakened old memories about what it means to flee.

Christa Nolte carefully lifted a little book out of a box of family papers.

"This is what my grandmother, Anna, took with her when we fled," she told me. "It was important for her to save it."

It was a pocket-sized Lutheran hymnal, the Silesian Church's Songbook.

Christa was a war baby, born in April 1943. Her family came from the town of Goldberg in Silesia, which back then was part of Germany. Today it's in Poland.

"We left in early 1945, my mother, my grandmother, my brother and me," Christa said. "The Red Army was coming. It was very cold."

The family took very little with them. Just a few pieces of cutlery, her brother's teddy bear and a feather duvet, which her mother, Margarethe, stuffed into her pram. Christa, not quite two years old, sat on the top.

"My mother originally wanted to get to her brother in Berlin," Christa told me.

"But our train was stopped just outside Dresden because the Allied aerial firebombing of the city had just begun."

I had met Christa in Saxony, in eastern Germany. She had just come from Berlin, where she had taken part in a church choir festival, along with a group from Coventry, another city blitzed during World War Two. Quiet and contained, she told me her story matter-of-factly, without drama.

Outside Dresden, the family set off on foot, through the snow and extreme cold. They eventually reached a camp a little way off south-east, in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia. Christa got very sick, with measles and then pneumonia. The child in the next bed died. She remembers people crying and air raid sirens - sounds that still haunt her.

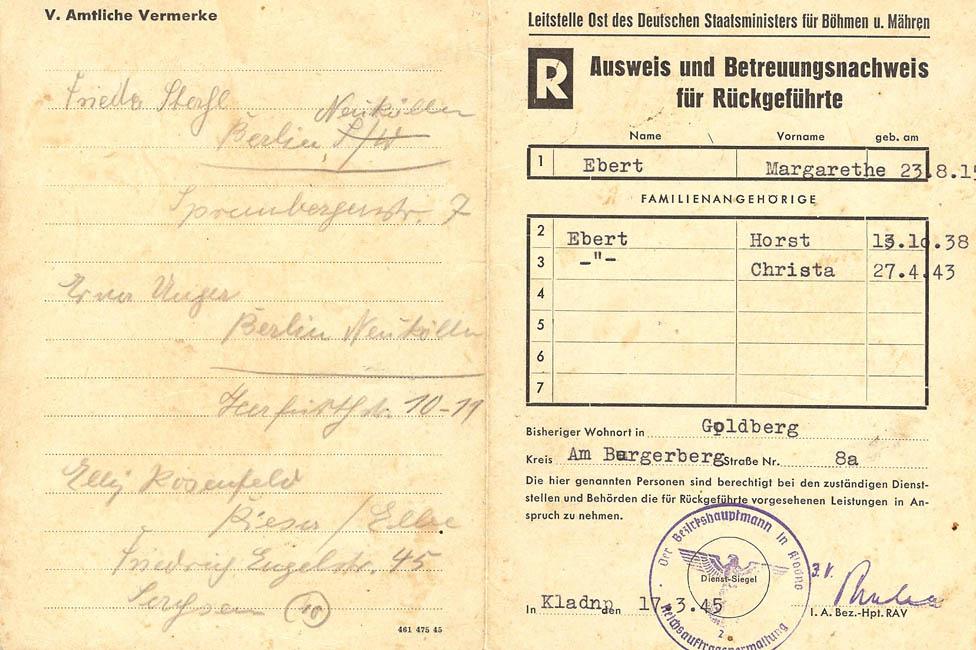

Christa's mother's ID card at the Kladno camp

At the end of the war, the family managed to get back to Goldberg - partly on foot, partly by train. At one point, they were surrounded by Russian soldiers, one of whom accosted her mother, Margarethe. She was terrified he meant to rape her, but instead he gave her a piece of ham.

When they got back home, everything had changed. Polish families from eastern regions, which had been transferred to the Soviet Union, had been moved into Goldberg and into their family home.

At the Potsdam conference in the summer of 1945, the Allies agreed that the German territories east of the Oder-Neisse rivers - including Goldberg - should be given to Poland.

So in 1946, Christa and her family left again - to become part of a mass exodus west. "We were on a train for nine days. We didn't know where we were going. We all had lice and fleas," Christa remembered.

She turned to me, with a rueful smile. "When we eventually got to the Rhineland, west of Duesseldorf, the farmers we were sent to live with didn't want us either. The first thing they asked us was: 'Are you Catholic or Protestant?' They were Catholic. We were Protestants. It was our biggest mistake."

Stories like Christa's are common. During my short stay in Saxony, I met a number of people who had come from Silesia or East Prussia as children. I also discovered that the old manor house where I was staying had been used as a refugee camp for Germans from the east well into the 1950s.

For many years, the fate of the ethnic Germans has been an uncomfortable topic - always overshadowed by Nazi atrocities, and repeatedly exploited by far-right groups.

"There are books about it, and we talk about it among ourselves," Christa told me. "I don't feel so badly affected. Children manage everywhere and in the end things didn't go so badly for me in the West - although the local children called us names for years."

But seeing Syrian refugees arrive in Germany today makes her think.

"Their experience is like ours - like that of our mothers and grandmothers - the rapes, sleeping rough, trying to keep your children safe."

"You mention rape," I said. "Did that happen to your mother?"

"She never spoke about it," Christa said. "Never."

Find out more

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service, or on Radio 4 on Saturdays at 11:30 BST

It was only in 1990, after the fall of Communism, that Christa and her mother were able to visit their old home again - Goldberg, now known by the Polish name Zlotorja.

Christa says Margarethe had made peace with the fact that Polish families were now settled there. "It would be a huge injustice if they had to move," she'd said. "Where would they go?"

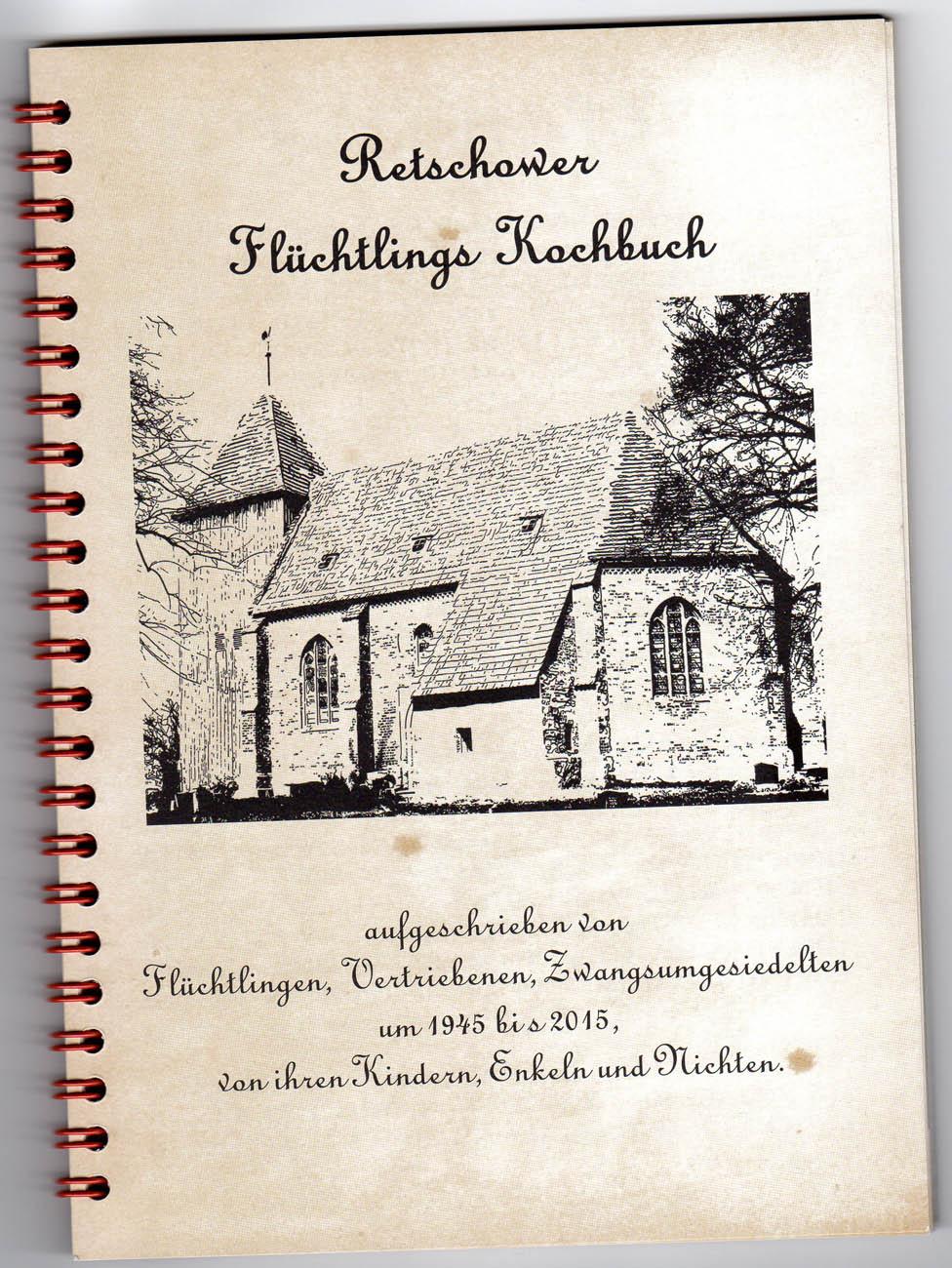

A week after our conversation, I received an email from Christa, who had gone on to visit Germany's Baltic coast near Rostock. It contained the photo of a refugee cookery book, recently put together by a local community there. The recipes were from Silesia, East Prussia, Afghanistan and Syria.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.