War and fertility: How losing a pregnancy in Iraq changed my approach to miscarriage

- Published

When a woman loses a baby in a developed country, all too often she is left to cope with the loss in silence. It can be an isolating experience. But when writer Amy McTighe had a miscarriage in Iraq, her Kurdish companions rallied to her support - and gave her a fresh perspective on her problems.

For four years I have been writing a book on the Kurdish struggle against Saddam Hussein's regime in Iraq, and for two of those years I have been trying to have a baby. In April this year these two objectives clashed when I discovered I was pregnant just before I left for a research trip.

As anybody who has struggled with fertility knows, it is a soul-sapping endeavour - a constant cycle of hope and disappointment, drugs, hormones, investigations, waiting lists and decisions. It gradually sucks away your identity and takes over your life. To avoid being dragged any lower than I already was, and after discussion with doctors and my partner, I decided to go ahead with the trip to Kurdistan - there was no medical reason not to.

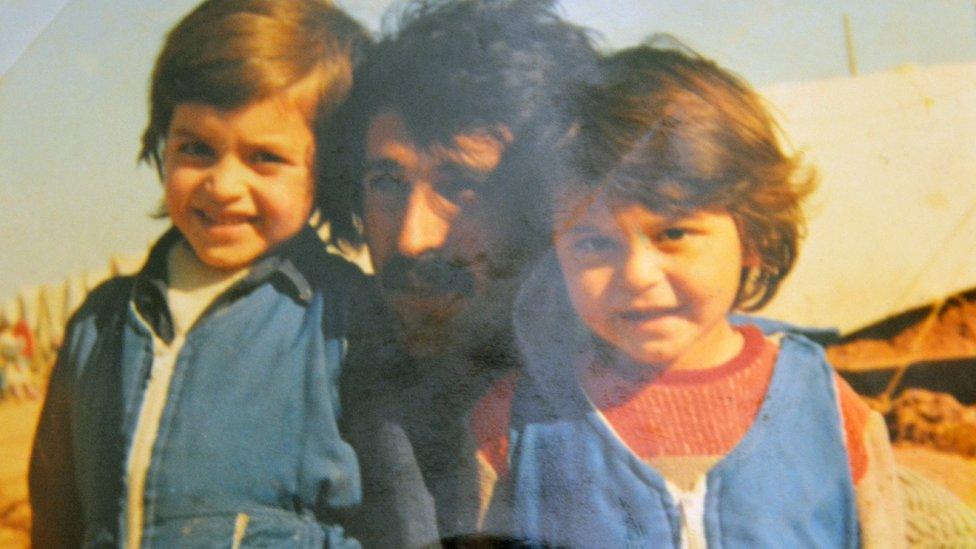

Kavout with her father, Zubeyr, and sister Kavy in the refugee camp near Merdin in Turkey, where they lived for three years

I was travelling with my friend Kavout who in 1988 had fled Iraq with her family, pursued to the Turkish border by the Iraqi army and their chemical bombs. Along with tens of thousands of others, she spent several years in a Turkish refugee camp before eventually being resettled in France in the early 1990s. Kavout's father was a Peshmerga - a Kurdish fighter - and we were in Kurdistan to visit the places he talks about in tales of his family's struggles during Saddam Hussein's persecution of the Kurds.

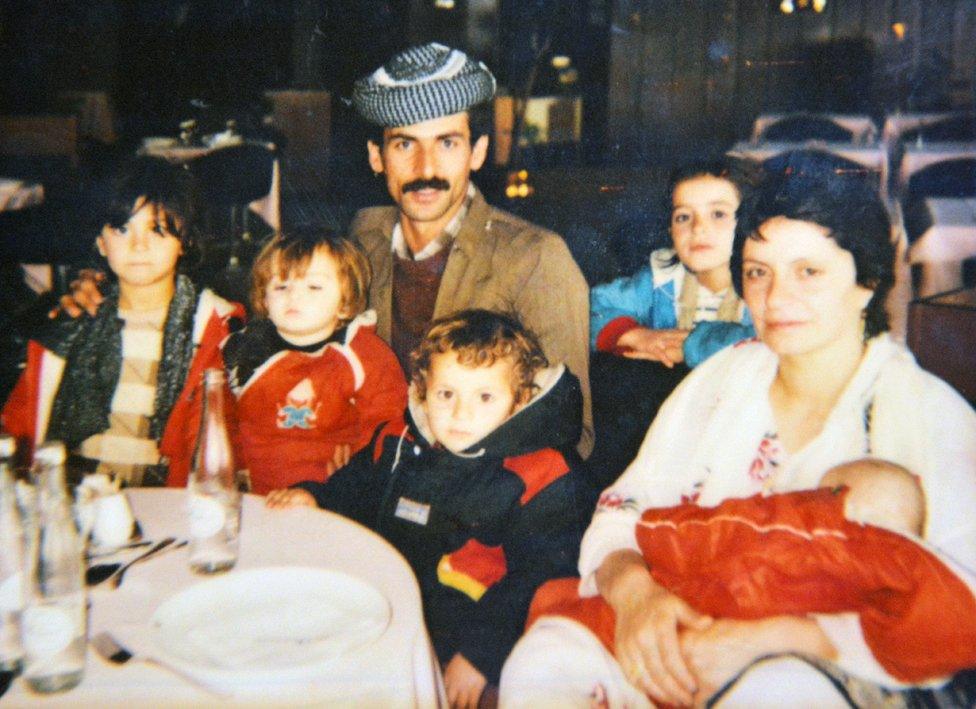

Kavout and her family on their arrival in France as refugees

When we arrived in Irbil I started to bleed. Kavout and I lay side-by-side on thin mattresses on the floor at night, searching the internet on our phones for symptoms. Alongside the blood was pain - sharp, stabbing little pains that seemed to hint at an ectopic pregnancy. The prospect of serious complications in a country where medical standards were under-par terrified me.

My medical encounters over the next couple of days ranged from confusing to humiliating to frightening. Even finding painkillers was fraught with danger because so many medicines are counterfeit.

It came as a relief to realise that I was just going through the sadly familiar but less dangerous experience of an early miscarriage. This time, however, I was without the normal comforts to help me through. The raging heat sapped my energy, water supplies were regularly cut off so I couldn't shower, and sometimes the only toilets available were outdoor, squat ones with a watering can beside the hole in the ground.

As the worst passed, I buried my sadness and pain in work. Propped up by cushions and fortified with sweet tea, I began to interview people who had survived the horrors of Saddam Hussein's persecution.

I spent time with families in villages and towns scattered across north-western Kurdistan and, as I confided with the women I met about my miscarriages, it seemed to unlock a kinship I hadn't felt before.

In Kurdistan, fertility is front and centre of family life - the women I met normally had between six and 10 living children and had lost at least as many during pregnancy or infancy. Until a few years ago, having babies in the Kurdish countryside was as raw and dangerous an experience as 200 years ago in Europe, so infant mortality was extraordinarily high.

Everybody I met was focused on how to get a baby, and they all had comforting words and advice. My friend Silav's mother told me that some women need to bind their stomachs during pregnancy. Kavout's mother made me promise that next time I got pregnant I should just lie in bed, because I clearly had a weak uterus.

To begin with, I found it refreshing to be able to discuss my problems so freely, since in the UK the norm is to disguise the first three months of pregnancy, with the implication that early miscarriages are to be hidden, along with your grief and physical pain.

But this was also the first time that my failure to carry a baby was being linked to things that I was or was not doing. Back home, I staved off guilt when I lost pregnancies because I had followed all medical advice to the letter. Doctors consistently told us it was "just bad luck". Now doubt began to creep in.

A week or so after my miscarriage, Kavout and I travelled to the ancient city of Amedi, perched high on a rocky outcrop in the midst of one of Kurdistan's spectacular mountain ranges.

The ancient gate of Amedi, in a liberal part of the country

The city is known for being more liberal than elsewhere - I saw few women with headscarves in public. We arrived at the house of some of Kavout's distant cousins and they immediately laid out a feast of fresh bread, rice, meat and yoghurt on a plastic tablecloth on the floor.

Our host's daughter, Samira, was in her early 30s and unmarried. She dressed in jeans and a shirt and looked healthy and happy, spending the afternoon hiking through the family orchards with us. Also at the house was her sister-in-law, Nadia. She was the same age, but thin and haggard - her skin sallow and drawn. She made the food for every meal, hovered nervously in the background without eating, and then cleared it all away, catering for a house full of relatives and guests almost entirely by herself.

That night the main house was full so we went to stay at Nadia's. She and her husband Islam live in a small apartment nearby, on the top floor of one of the city's ancient stone houses.

View of Amedi from across the valley

Nadia's home is cosy and peaceful but she hardly spends any time there. Instead, she has to get up before breakfast each day to go to her in-laws' house and prepare their food. Then she looks after her sister-in-law's children, makes lunch, then dinner. She returns home at the end of each day, well after sunset, completely exhausted.

While it's common for extended family members to share their resources and efforts and to eat together for most meals, Kavout told me that Nadia is particularly put upon in the family because of her inability to have children. They had initially sent her to local doctors for IVF and then abroad for tests. French doctors told Nadia that her fertility had been ruined by over-stimulation. In their opinion, Nadia simply didn't have any eggs left.

After this, Nadia was not commiserated with or supported but gradually became a sort of servant, denied the social privileges that others in the family enjoyed. It is as though she has been proven useless as a woman and therefore deserves no respect.

At 32, Nadia feels like a failure. Her in-laws want their son to take a second wife - a common response to infertility in Kurdistan - but he refuses. He, at least, is tender and kind towards his wife, seeing her as his life partner rather than a failed mother.

The pressure I felt from only a few days of well-intentioned help and advice gave me a little insight into Nadia's frame of mind. Kurdish society seemed completely obsessed with churning out as many children as possible.

I had noticed while writing my book that this focus on reproduction had persisted even during the most dangerous times, where Kurdish people were savagely persecuted, sometimes simply for existing.

My friend Silav was born in 1987 beside a stream in the inhospitable mountains of the Turkish-Iraqi border, where her mother hid in caves while her father was fighting in the resistance.

Silav stands beside the mountain stream where she was born

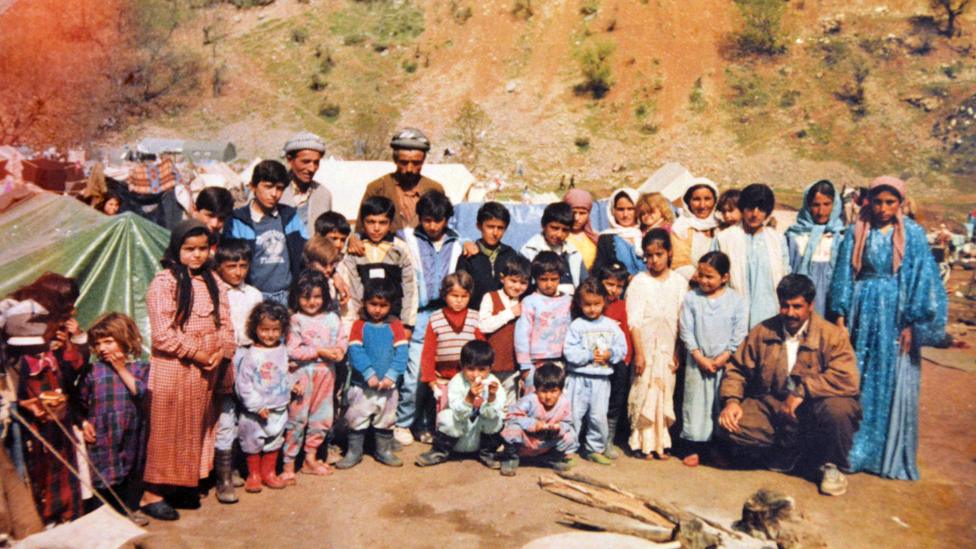

When Kavout's family fled chemical bombs in 1988 and were forced into a Turkish refugee camp, her parents brought another three children into the world at a time when they didn't know whether they would be sent back to their deaths in Iraq. They weren't alone in this. Kavout's father Zubeyr told me that the population in the refugee camp more than doubled in three years, in spite of high mortality amongst the young and old.

A baby in a home-made cot in a refugee camp

I had always just assumed that this was because Kurdish people didn't have contraception, but one day I asked Kavout about it directly: "Why did your parents bring so many children into the world when their lives were so unstable and their children would face so many dangers?"

"Because they were told to," she said. "Saddam was trying to exterminate us, so they needed to keep having children to ensure our survival. The [Peshmerga] leadership actually told them to."

For decades, Iraqi Kurds had been persecuted and killed in huge numbers. Their lives were unimaginably hard and there was no certainty that every, or indeed any, Kurdish child would live to adulthood. The more children they had, the more chances there were that some might make it. Kurdish women played many vital roles in the rebellion - fighters, smugglers, messengers or healers - but bearing children was the most important of all.

A large family group in a refugee camp in Turkey in the 1990s

This was a major challenge to the attitude I was used to, where having children is seen as something that you should plan, to ensure that you have the emotional and practical resources to care for a child. This was reproduction stripped back to its essential role - survival of the species.

Attitudes do, however, seem to be changing. With relative peace, and after spending time overseas as refugees, many Kurdish women are changing their priorities. Silav has declared that she never wants children. Kavout hasn't written it off, but is currently focussed on her career. Neither feels any pressure from their families, who are just happy to see them reaping the rewards of decades of struggle.

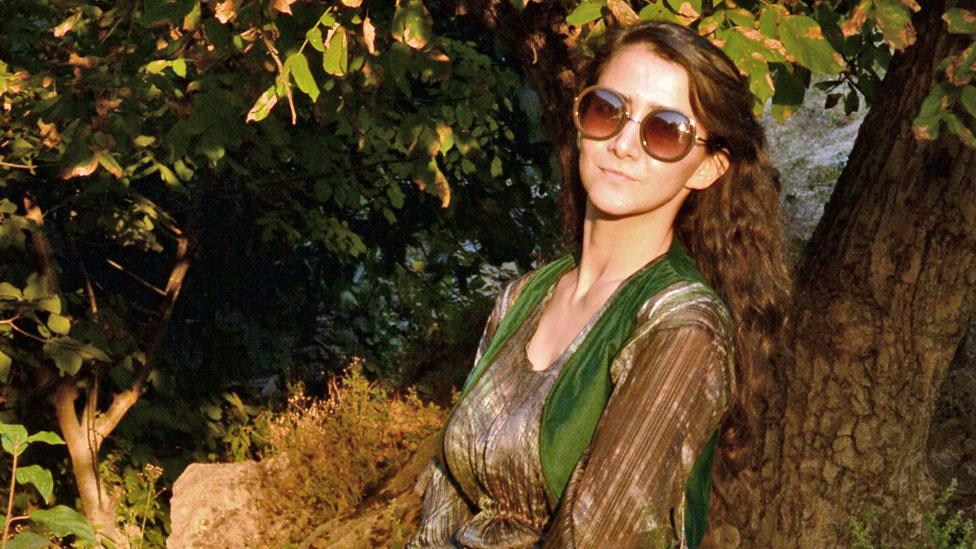

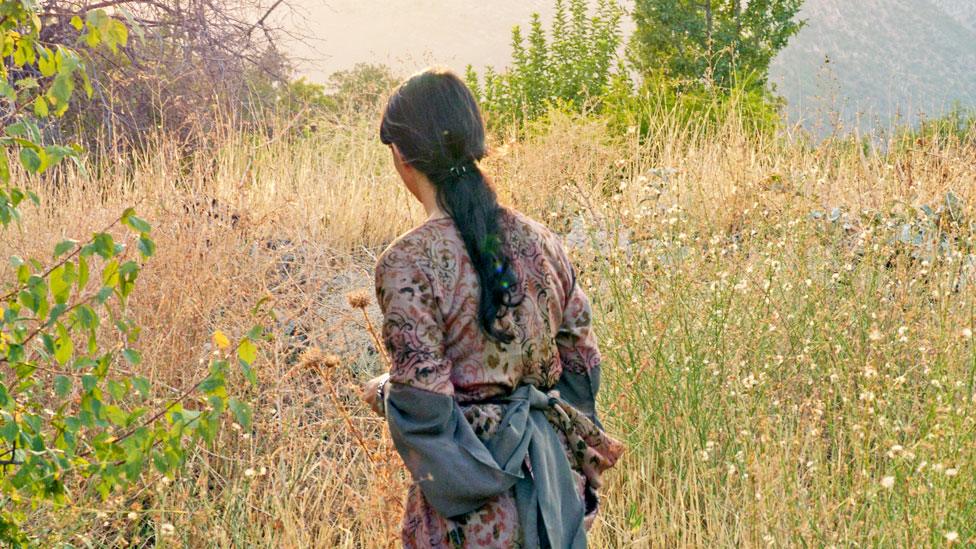

Silav in the fields around the village where she grew up - since destroyed by Iraqi troops

And what about those who are still struggling? In the refugee camp of Domiz, where mostly Syrian Kurds live, I met Rania, carrying her little girl and waiting for a check-up in the Medecins Sans Frontieres midwife unit after a recent miscarriage. She had fled the intense bombing of Damascus a year earlier and didn't know when - if ever - she could go home. Rania thought her miscarriage had been caused by the shock of her mother's death, but when I asked when she would start trying again, she told me that she wouldn't have any more children yet. Her life was too uncertain to bring another into the world.

Rania and her daughter

A few weeks after my own miscarriage, Kavout and I attempted to climb Mount Halgurd, Iraq's highest mountain on the border with Iran. I wanted to get some idea of what it was like for those fleeing Saddam's armies in in the 1980s and 90s.

Amy, Kavout and their guides climbing Halgurd, shortly after wandering across an uncleared minefield

Our trek was fraught with danger. An old man we passed told us not to stray from the path because landmines were everywhere, but as we got higher, snow obscured the edges of the tracks so we couldn't tell where we were walking. On the bleak, exposed mountainside, storms rolled in without warning and temperatures plunged. We caught fleeting glimpses of wolves and sinister armed men. Somewhere around midday I realised that I had food poisoning and began to black out intermittently, dropping to my knees until the world came back in view, then struggling back upright.

We reached a point where snow drifts obscured a narrow path cut into a steep mountainside of loose scree, and our choice if we continued was to risk slipping to our deaths on melting snow or being blown up by a landmine by leaving the path. I finally broke.

A landmine on the mountain

As well as providing background for my book, I had seen this climb as a symbol of my perseverance and I couldn't bear the thought of failing. Reason crept in to argue that risking all of our lives wasn't worth it. I sat in the snow and cried a little, then ate an energy bar and turned back down the mountain. I had given everything I could.

Back in Irbil, I spent several days in bed at my friend's house, recovering. By now I was feeling pretty heroic, even though I hadn't reached the top of the mountain. My friend's mother - a large, handsome woman in her early 60s - was sitting on the floor nearby, peeling vegetables. She asked where I had been and heard my story of danger and derring-do, then quietly told me how she and her children had fled from Iraqi troops through those same mountains in 1990 to get to Iran. She remembered the same fears I spoke about. "But imagine", she said, "going through that for eight days and nights, with no food or warm clothing, no rest, and aircraft shooting at you." Unlike me, when fear overwhelmed her she had no option but to continue. "If we went forward we might die, but if we turned back we would die for sure."

Amy and Silav's mother stand on Gara mountain

Back home, in my familiar environment and my familiar routine, do I have a new fortitude in facing fertility challenges after hearing what Kurdish women have faced and continue to face? No, I can't really say that I do. Loss and disappointment still grind me down. But I'm trying to take what I can from both Kurdish and British attitudes to fertility as I move forward. I trust in medical advice but also listen to the experiences of other women, I speak more openly about miscarriage to allow my friends and family to support me - and I try very hard not to blame myself.

Photographs by Amy McTighe. Family photographs used with permission. Some names have been changed.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.