The year my cancer changed everything

- Published

Carly Appleby wasn't convinced when doctors dismissed a small lump in her breast as insignificant. It turned out the young mother had stage three breast cancer. Here she describes the effect of the diagnosis in February 2017 - and the moment of truth she faced afterwards.

It's inevitably a beautiful sunny day in the Cotswolds when I am diagnosed with stage-three breast cancer - that's when it has spread beyond the area of the original tumour, in my case to the lymph nodes in my arm.

I'm sitting in the clinic with my husband. We're both stunned. I am 37 years old, relatively fit and healthy - or so I've always thought - with no family history of breast cancer.

When I first go to see my GP, she's fairly dismissive - fewer than five minutes to check me over. She finds a small lump in my breast - smaller than a grain of rice, hard, almost gritty. "It's probably hormonal, nothing to worry about. Come back if it doesn't go away," she says breezily.

A few months pass and I realise it's still there. I go back to see another doctor. This time I have more of a physical examination but the conclusion is the same: "It's probably a fatty lump." A sign of getting older, I tell myself.

But it bothers me. It doesn't feel right. My left breast feels sore when my daughter jumps on me or cuddles me.

Carly with long hair, before her cancer diagnosis

I ask to be referred to the breast clinic. I take my mother with me for moral support. I am nervous.

The consultant examines me and then blandly comments: "I don't think that's anything to worry about." Unfortunately, the ultrasound scan and mammogram show otherwise. I have a large area of calcifications - usually a sign of early breast cancer. They do a painful biopsy and test the lymph nodes under my arm.

It all has a profound effect on me. I've never thought about my own mortality. I still regard myself as a young woman rather than a middle-aged mum. But I worry at this point that I won't live to see Flo, my three-year-old, grow up.

I'm anxious about telling other people of my diagnosis but I want to raise awareness for other women and my friends, so I decide to go on social media. The supportive responses are overwhelming.

Treatment starts fairly quickly. I need six cycles of chemotherapy, have to get lymph glands removed from under my left arm, a mastectomy and then radiotherapy. It's going to be a long year, but at the end of it I hope to be cancer-free.

The first cycle of chemotherapy isn't as scary as I imagine. An intravenous drip dispenses my personal cocktail of drugs. Other drugs are given as slow injections into a cannula in my hand. It all takes three hours and I drink lots of tea.

Find out more

From Our Home Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers across the UK on life in the UK

Catch up on iPlayer, or listen to BBC Radio 4 on Sundays at 13:30 once a month

Watch Carly celebrate as she finishes her treatment on the BBC Gloucester Facebook page, external

I feel dreadful for the next few days - like a bad hangover without the good night out. No energy, no appetite, sick, extremely thirsty, everything aches. I'm miserable and down. But after that, I begin to feel more normal.

I'm glad to start treatment. I think of the chemotherapy zapping away the cancer a bit like a computer game - Pac-Man gobbling up all of the bad cells. Zap, zap, zap.

"Will I lose all my hair?" is one of the first questions I ask my consultant. "Yes," is her matter-of-fact answer. Call me vain, but I think this may be one of the hardest things about my diagnosis.

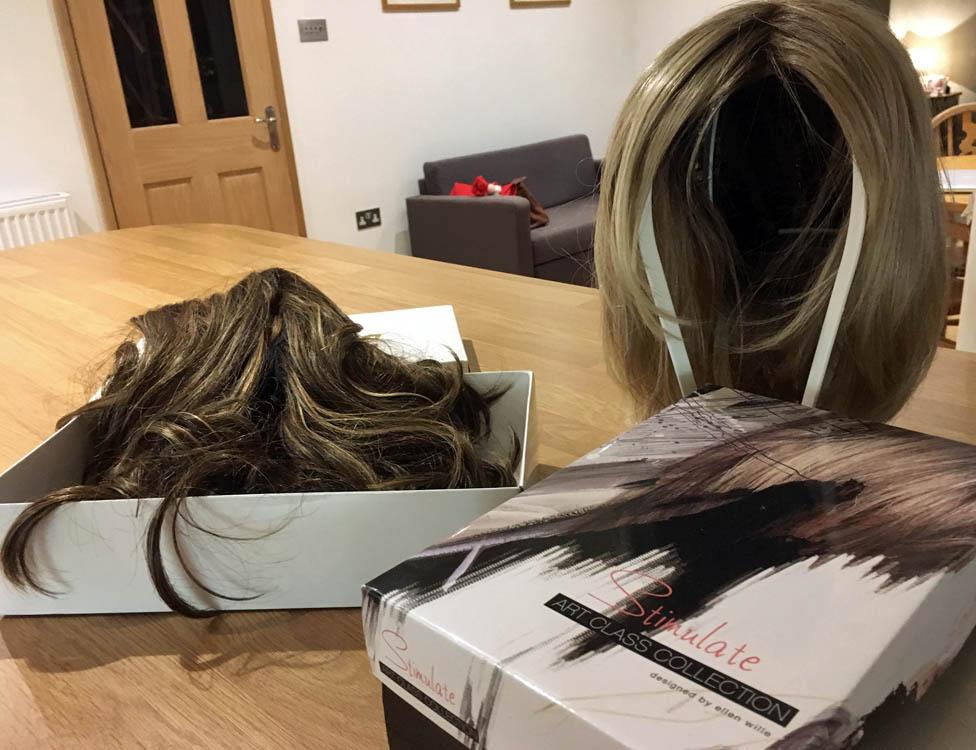

I start looking at wigs. "How about a blonde one, mummy?" asks my daughter. "Then you can look just like me!" I find strength in that companionship. Together, we settle on a short blonde wig. It even has pretend roots in the parting!

The mobile chemotherapy bus used by Carly

We decide my wig needs a name. As it's made in Germany, Betty or Bertha comes to my mind. "How about Chewbacca" - from Star Wars - my husband chips in, helpfully. "Or Hairy Maclary from Donaldson's Dairy?" suggests my daughter, mentioning one of her favourite books. How we laugh driving home!

A few days later I have my long brown hair cut as short as possible. I want to lessen the shock once it starts to fall out. It feels good to be in control of something.

I send my family and friends pictures of my new short hair. "You look younger!" exclaims my sister. I don't believe her.

My daughter struggles to understand all that's going on. She asks me if she'll lose her hair too - and she doesn't want to see me bald. "Who does?" I think to myself. We decide to buy her a little play wig.

She's still puzzled by one thing, though. "Why do I keep on getting so many presents, mummy?" There's been a stream of cards, flowers, parcels, messages of hope - oh, and food. Lots of delicious, tasty food. It's funny how differently we respond to news we all have to process.

Months later, I don't recognise myself in the mirror. Bloated from steroids, I have neither eyelashes nor eyebrows and I'm bald.

I gaze enviously at my husband's head and say: "I can't wait to have as much hair as you!" We both laugh. He doesn't have much, but more than me.

I get some weeks to recover from the chemotherapy before surgery - a mastectomy and auxiliary node clearance from under my arm.

On the day, I feel vulnerable about being operated on having no hair. I've been wearing headscarves or my wigs - we eventually settled on the names Betty and Brunetti. But I must do without them for my surgery.

Carly's two wigs, Betty and Brunetti

When I come round, I can't move. My legs are encased in an inflated blanket which moves noisily up and down to prevent blood clotting. There's an oxygen tube in my nose and I'm connected to a catheter. There's also a drain in place under my arm. The fluid in it resembles a strawberry milkshake. Although I can press a button for pain relief, I react badly to the morphine.

I opt for immediate reconstruction of my breast which means a temporary silicon expander is fitted. When I first look at my chest I'm disappointed to see that I'm quite flat. The implant will need inflating gradually to stretch my remaining skin.

My surgeon says the operation went well and she couldn't feel the tumour at all. She visits me twice in her own time. Similar in age to me, she really seems to care.

Living with breast cancer

One in eight women in the UK will develop breast cancer in their lifetime

Nearly nine out of 10 women survive breast cancer for five years or more

There are estimated 691,000 people alive in the UK after a diagnosis of breast cancer - this is projected to rise to 840,000 by 2020

Source: Breast Cancer Care, external

All the same, I have trouble moving, sleeping and dressing and have to stay in hospital for five days. My husband visits with Flo, who has turned four. She insists on carrying my drain to the toilet for me. It has to go everywhere I go. Finally it's removed - although when that happens it feels as if someone is tugging a rope from my insides.

I have my expander implant inflated regularly over the following weeks - 50ml of saline are injected at a time. "How much is needed?" I ask. "Four hundred," replies my surgeon, "the weight of your old breast."

"So there is science behind it!" I say. We both laugh.

Really, though, I'm upset. My scar looks ugly. No hair, no boob, no periods. Breast cancer really does strip all that's feminine from you. But I am alive! And the cancer is out.

I also draw comfort from the many other young women who are going through the same as me. The Younger Breast Cancer Network is an online group of 3,000-plus young women under 45 who share their experiences.

Carly Appleby after the return of her eyelashes

One day, I look in the mirror and see my eyelashes have returned. It's a big moment! My hair is also starting to grow again. Slowly, my energy is returning.

Five weeks after my operation, I'm told I've had a complete pathological response. This is the best possible news. It means there are no signs of cancer in either the breast or the nodes that were removed. The tumour was completely eradicated by the chemo. Pac-Man really did gobble up those cancer cells.

It takes some getting used to, to be told there is no evidence of disease after months of anxiety. I have a CT planning scan to prepare for radiotherapy and have my first-ever tattoos - three small green dots so the technicians know where to line me up and direct the beams.

I have chemo injections every three weeks in my thigh and I start taking a hormone treatment that's going to be part of my daily routine for the next five-to-10 years in an effort to prevent the cancer returning.

Together, though, these produce menopausal symptoms. Hot flushes and night sweats are two more things I didn't think I'd be dealing with in my 30s.

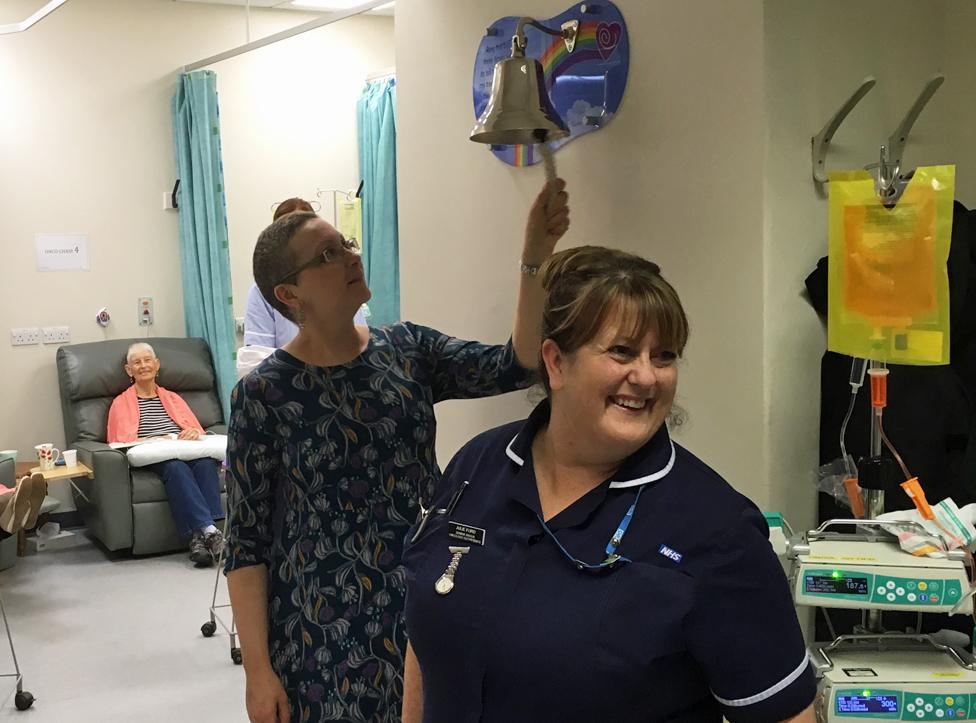

I have 15 sessions of radiotherapy altogether, travelling every day to the hospital for treatment. On social media, I notice that many patients ring a bell to mark the end of their treatment. With the charity End of Treatment Bells, I arrange for one to be installed in the oncology unit at my hospital.

Shortly afterwards, I ring that bell loudly and everyone in the ward stops to clap. I hug the oncology nurse - I can't believe it's over!

I meet some women from Knitted Knockers - it's a charity that makes special handmade breast prostheses for free. They offer to knit one for me. I now have one perky breast and another that's been affected by gravity and breastfeeding. The knitted knocker is marvellous and helps to even me out.

Someone told me having cancer makes you realise how much you are loved. Towards what I now believe is the end of my journey, I'm still finding that's true.

More from the BBC

Sharon is a volunteer for Knitted Knockers

Sharon is a volunteer for Knitted Knockers, a charity that hand-makes woolly prostheses for women who've had mastectomies - like her.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.