The Tattooist of Auschwitz - and his secret love

- Published

For more than 50 years, Lale Sokolov lived with a secret - one born in the horrors of wartime Europe, in a place that witnessed some of the worst of man's inhumanity to man.

It would not be shared until he was in his 80s, thousands of miles from that place.

Lale had been the Tattooist of Auschwitz.

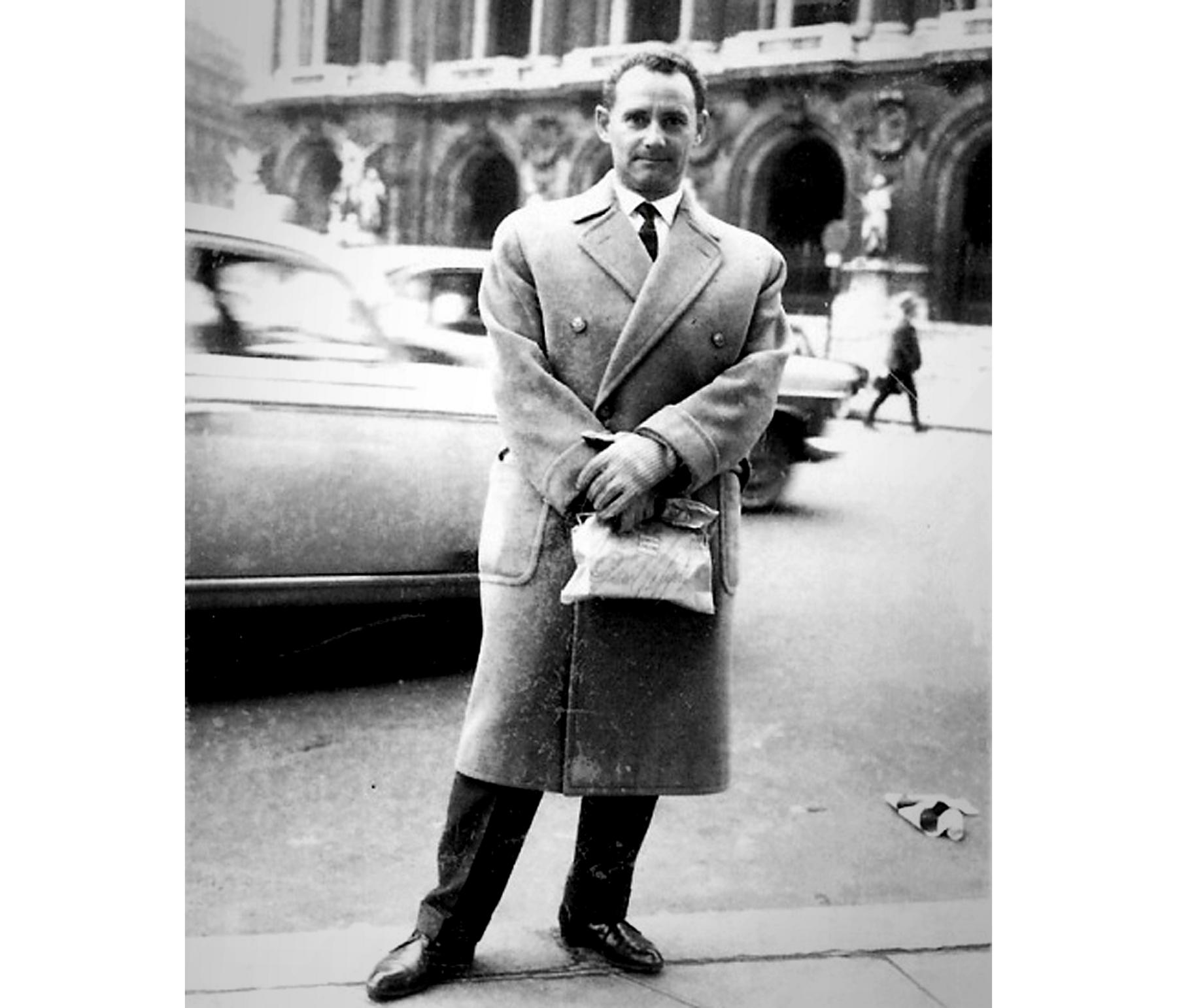

Living out his life in a suburb of Melbourne, the man who had been born Ludwig "Lale" Eisenberg to Jewish parents in Slovakia in 1916 decided to share his story.

"This man, the tattooist from the most infamous concentration camp, kept his secret safe in the mistaken belief that he had something to hide," says Heather Morris, who spent three years recording Lale's story before he died in 2006.

She has now written a book - The Tattooist of Auschwitz - based on how he tattooed a serial number on the arms of those at the camp who weren't sent to the gas chambers.

"The horrors of surviving nearly three years in a concentration camp left him with a lifetime of fear and paranoia," she says.

"The story took three years to untangle. I had to earn his trust and it took time before he was willing to embark on the deep self-scrutiny that parts of his story required."

He feared that he would be viewed as a Nazi collaborator. Keeping the secret, or what he described as a burden of guilt, would protect his family, he thought.

It was only after his wife Gita died that he "unburdened" himself, revealing a tale not only of survival but of deep love.

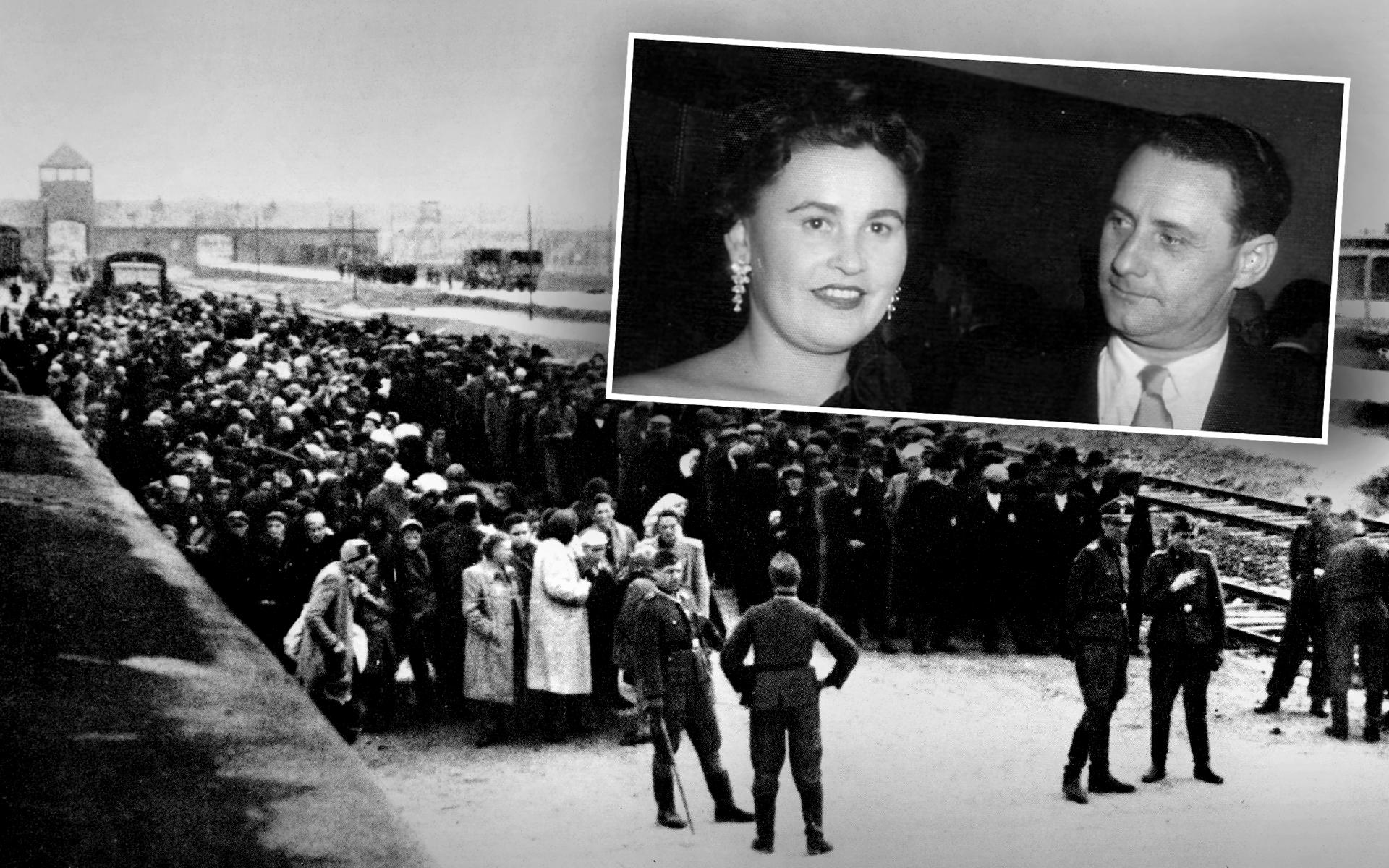

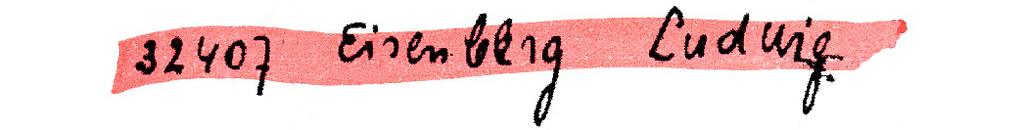

Prisoner 32407

In April 1942, aged 26, Lale was taken to Auschwitz, the Nazis' biggest death camp.

When the Nazis came to his hometown, Lale had offered himself as a strong, able-bodied young man in the hope that it would save the rest of his family from being split up. Unlike his siblings, he was unemployed and unmarried.

At that time, he did not know of the horrors that went on at the camp in occupied south-west Poland.

On arrival, the Nazis exchanged his name for a number: 32407.

Prisoner number 32407 was set to work like many others, constructing new housing blocks as the camp expanded.

He spent hours working on the rooftops, keeping a low profile from the SS guards and their unpredictable tempers.

But shortly after he arrived at Auschwitz, Lale contracted typhoid.

He was cared for by the man who had given him his identification tattoo, a French academic named Pepan.

Pepan took Lale under his wing and set him to work as his assistant. He taught him not only the trade, but how to keep his head down and his mouth shut.

Tattooed arms of Auschwitz prisoners

Then one day Pepan disappeared, shipped out. Lale would never find out what happened to him.

Partly because of his skills with languages - he knew Slovakian, German, Russian, French, Hungarian and a bit of Polish - Lale was made the main tattooist, the tetovierer, of the death camp.

He was given a bag full of tattooing supplies and a paper bearing the words: Politische Abteilung.

Lale now worked for the Political Wing of the SS. An officer was assigned to monitor him, which gave him a semblance of protection.

Aerial view of Auschwitz in World War Two

As the tetovierer, Lale lived a step further away from death than the other prisoners.

He ate in an administration building. He was given extra rations. He slept in a single room. When his work was done, or when there were no new prisoners to tattoo, he was allowed free time.

"He never, ever saw himself as being a collaborator," Morris says.

It was a real concern after the war - many saw the prisoners who worked for the SS at the camps as having taken part in their brutality.

"He did what he did to survive. He said he wasn't told he could have this job or that job,'' says Morris.

"He said you took whatever was being offered. You took it and you were grateful because it meant that you might wake up the next morning."

Despite his privileges, the threat of not waking up the next day was ever present.

Josef Mengele (left) with other senior Nazi officers

"[Josef] Mengele, in particular, was a common sight as he chose his 'patients' from the new arrivals, sending them Lale's way," Morris wrote.

"On many occasions while whistling an operatic tune, he would sidle up to Lale and loudly terrorise him: 'One day, tetovierer, I will take you - one day.'"

Child prisoners at Auschwitz - photographed on orders of Josef Mengele

For the next two years, Lale would tattoo hundreds of thousands of prisoners, with the help of assistants.

These forced tattoos, the numbers shaky and stark against pale forearms, have become one of the most recognisable symbols of the Holocaust and its deadliest camp.

Only prisoners at Auschwitz and its sub-camps, Birkenau and Monowitz, were tattooed.

The practice began in autumn 1941 and by the spring of 1943, all prisoners were tattooed.

Children of Auschwitz show their tattooed arms

At first, a metal stamp was used to imprint the entire number into the skin. Ink was rubbed into the wound.

When this method proved inefficient, the SS introduced a twin-needle device.

This is the tool Lale used during his time as tattooist.

When prisoners arrived at Auschwitz, they were selected either for forced labour or immediate execution.

Their heads were shaved, their belongings taken.

Arrival of prisoners at Auschwitz

Women prisoners at Auschwitz deemed "fit for work", 1944

They exchanged their clothes for rags, and then lined up to receive their mark from the tetovierer.

The only exceptions to this branding were the "re-education" prisoners of German ethnic origin and those sent directly to the gas chambers.

It was the final peg in the brutal "registration" process, says Dr Piotr Setkiewicz, head of the research centre at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum.

"It was one thing in a series of humiliating, dehumanising things that happened on arrival to the camp.

"First it was painful, and second they understood at this moment they were losing their names. From this time on, the prisoners did not use officially their names. They had to use their numbers."

Prisoner 34902

It's July 1942 and Lale is handed another piece of paper. In front of him are five digits: 3 4 9 0 2.

Tattooing men is one thing, but when he holds the thin arm of a young girl in his hands, he feels horrified.

He has not yet been made the tetovierer. Pepan urges him to do as he's told. If he doesn't, he will condemn himself to death.

There is something about this girl and her bright eyes.

Years later, Lale will tell Morris how in that moment, as he tattooed her number on her left arm, she tattooed her number in his heart.

He learned that her name was Gita - she was in the women's camp, Birkenau.

With the help of Lale's personal SS guard, he would smuggle letters to her. Letters led to secretive visits outside her block.

He tried to take care of her, sneaking her his extra rations, even getting her moved to a better work station. He tried to give her hope.

"Gita, she had her doubts, very strong doubts," Morris says.

"She didn't see a future. He always, deep down, knew that he was going to survive. He didn't know how, but it comes back to that whole notion of being a survivor. He's a survivor because of luck, being in the right place at the right time, and being able to manipulate opportunities that he saw."

Knowing he was one of the lucky ones, Lale tried to help as many fellow prisoners as he could in his capacity as tetovierer.

Food was the currency of Auschwitz, and he used his privileged rations to feed his former blockmates, Gita's friends, and the Roma families that arrived later on.

He began trading jewels and money - given to him by other prisoners - with the villagers who worked near the camp to obtain more food and provisions for the most needy.

Women at Auschwitz shortly after liberation by Soviet forces, 1945

In 1945, the Nazis began shipping prisoners out of the death camp before the Russians arrived. Gita was one of the women selected to leave Auschwitz.

The woman he had fallen in love with was gone. Lale knew only her name - Gita Fuhrmannova - but not where she had come from.

Lale eventually also left the camp and made his way back to his hometown of Krompachy in Czechoslovakia.

He paid his way with the jewels he'd managed to steal from the Nazis. His sister Goldie had survived and so his childhood house still belonged to his family.

The only thing left was to find out what happened to Gita. Could he dare to hope that he would ever find her again?

Jewish families heading from Czechoslovakia towards US-controlled zones in Austria in 1946

In a horse and cart, he set off for Bratislava, the entry point for many survivors returning home to Czechoslovakia. Lale waited at the railway station for weeks, until the stationmaster advised him to go to the Red Cross instead.

On his way there, a young woman stepped into the street in front of his horse. It was a familiar face. A pair of bright eyes.

Gita had found him.

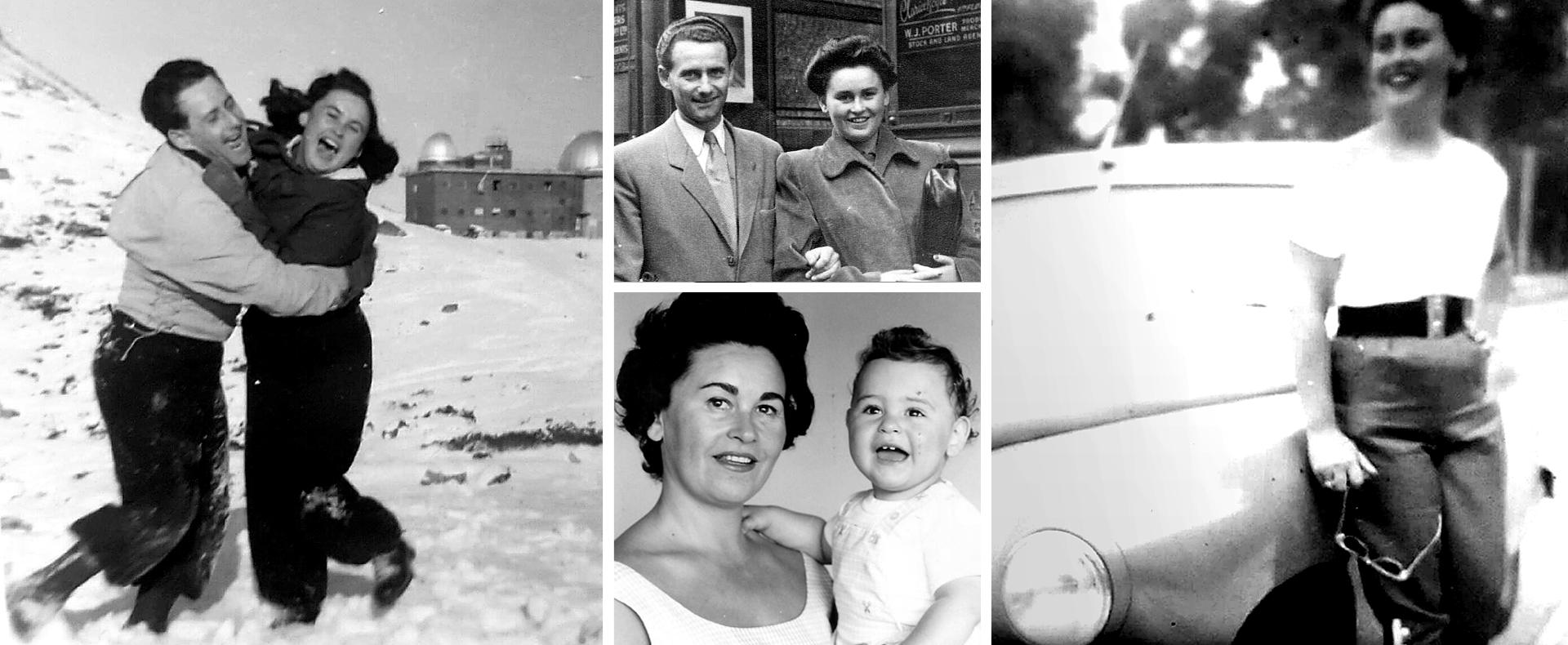

Lale and Gita Sokolov, 1940s

The couple married in October 1945 and changed their last name to Sokolov to better fit into Soviet-controlled Czechoslovakia. Lale set up a textile shop that was successful for a time.

But they had been collecting and sending money out of the country to support the movement for an Israeli state.

When the government discovered this, Lale was imprisoned and his business nationalised.

It was while on weekend leave that he and Gita made their escape from Czechoslovakia.

They went first to Vienna, then Paris, and finally, in an effort to get as far away from Europe as they could, set sail for Sydney. During the journey, they met a couple from Melbourne and were convinced to start a new life there.

Lale started a textile business again, and Gita began designing dresses. In 1961, they had a son, Gary.

Family snaps of Lale and Gita Sokolov - including their young son, Gary

Melbourne in 1955

Lale and Gita lived out the rest of their lives in Melbourne.

Gita visited Europe a few times before she died in 2003. Lale, on the other hand, never returned.

Only close friends knew of the couple's love story.

Photo of Gita and Lale Sokolov before Gita's death in 2003

"I met several of his friends who all would immediately want to tell me, 'You know he and Gita met in Auschwitz? Who falls in love in a concentration camp?'" Morris says.

Even Gary would not know the full extent of the horrors his parents endured until years later.

In fact, the full truth came to light only after Gita's death, when Morris came into the picture.

Getting the story

"I didn't find the idea - the idea found me," Morris says.

Gary was searching for someone to tell his father's story and found Morris through a network of friends.

Morris is not Jewish and that, she says, is why Lale - who was then 87 - chose to share his story with her.

"I questioned him about that straight up," Morris says. "To him it was important that I had no baggage. He needed somebody who was perhaps naive, and who would hear his story and accept his story for how he was going to tell it.

"To him, it was all about looking into those eyes of that 18-year-old girl," Morris says.

Lale Sokolov with writer Heather Morris

Over the next three years, Morris would visit Lale several times a week. Most of what he remembered matched her own research.

In addition to Lale and Gita's love story, the Tattooist of Auschwitz, the book Morris has written, brings to light a new piece of Holocaust history. The process of corroborating the anecdotes Morris gathered from Lale was key.

Initially the novel was meant to be a screenplay. As a result, Film Victoria, the Australian government's film body, agreed to fund international research for the project.

"We had researchers out of the country, professional researchers who then went and examined and found the documents - found amazing documents to verify what he said," Morris says.

Those documents led to the discovery that Lale's parents had been killed at Auschwitz a month before he arrived.

Lale died in 2006, before he learned what happened to his parents.

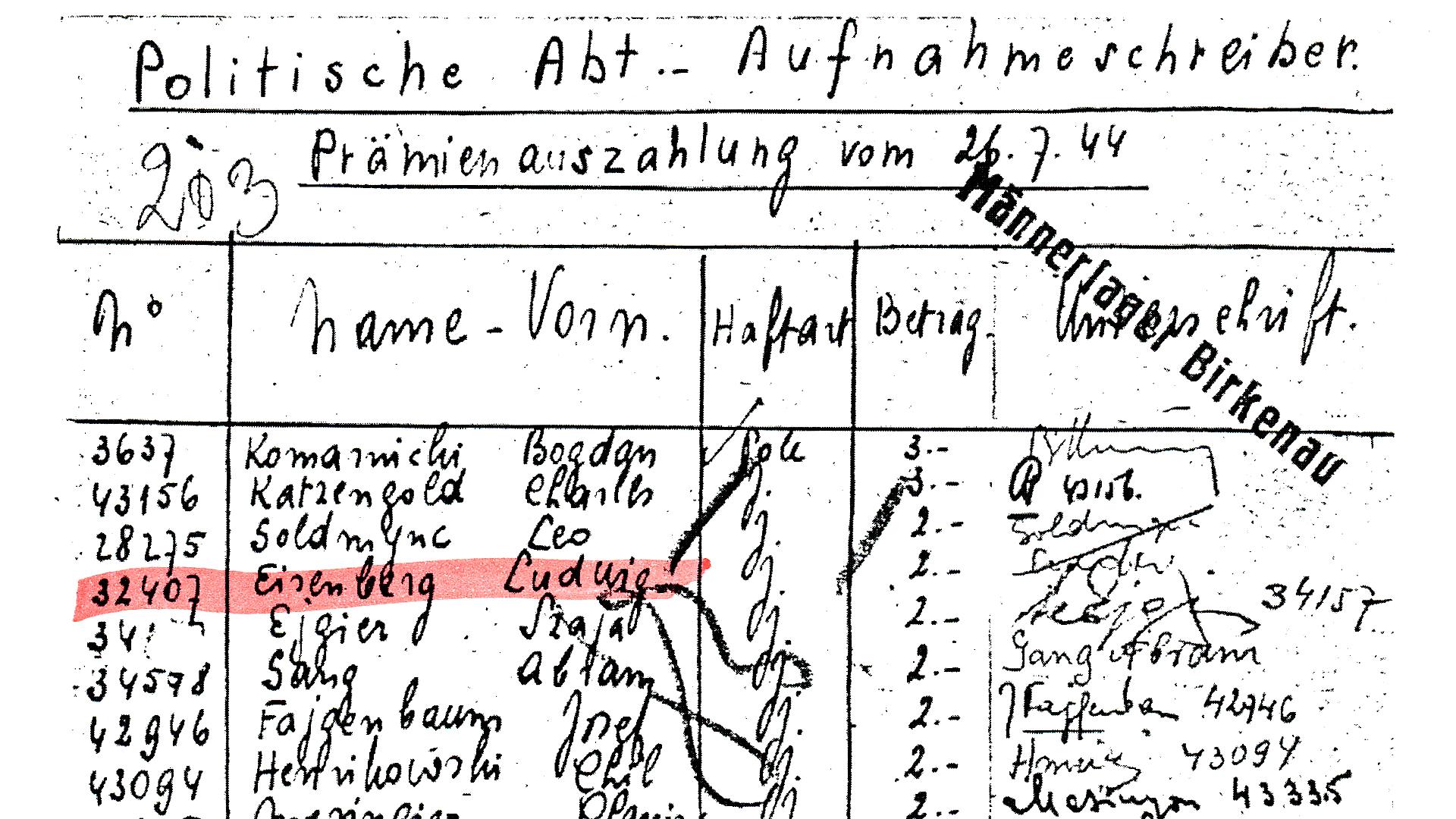

Regarding other documents, one was discovered with Lale's name and number in a list with other prisoners.

"The top of the document says Politische Abt - Aufnhmershreiber, Pramienauszahlung vom 26.7.44, which translates to - Political Wing Admittance Writer," Morris says.

The document did not list specific jobs, but Morris and the research team "considered it enough proof he was working for the Political Wing."

Cedric Geffen, president of Holocaust-memorial organisation March of the Living Australia, says he was "fascinated" by Lale's story.

"I had not given much thought to the question of the identity of the tattooist and whether or not they had been prisoners whom the Nazis forced into doing this unthinkable task," he says. "I personally had not really reflected at length or in depth about the many questions around this role and the ramifications for the tattooist."

For Geffen, telling this story helps younger generations, those who never lived through these horrors, forge connections with history.

"It breaks it down into tangible emotions and experiences that undoubtedly accompanied each and every person that went through this period, most of whom did not live to tell their story," Geffen says.

"It is important to tell this story as it humanises a role that very few people think about when thinking about this horrific period," he adds. "Who was the person tasked with inflicting this horrendous physical degradation? Why did he do it? What was his life like? Whatever happened to him?"

The Tattooist of Auschwitz by Heather Morris is published by Bonnier Zaffre and released in the UK on 11 January 2018.

Unless stated otherwise, all images copyright Heather Morris/Sokolov family.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.