Why I took my wife's last name

- Published

These days many women keep their own name when they marry, and couples are increasingly opting for a double-barrelled or merged name. But men who take their wife's surname are still quite rare. Kirstie Brewer spoke to three.

Rory, a primary school teacher from south-east London, left for the summer holidays in 2016 as Mr Cook and returned to start the new school year as Mr Dearlove. It caused some confusion among his class of seven and eight-year-olds. A few female teachers had changed their last names when they got married - but never a man.

"Why did you change your name, Mr Dearlove?" asked one of the girls in his class, while Rory was on playground duty. "Because I got married. Look!" said Rory, showing the child his wedding ring. "But why?" she insisted.

"Because when you get married you can choose what name you want. You can keep your name, or both have the same name, or make a new name. I chose my wife's name, Dearlove," Rory explained.

"The stuff children see at school they accept as normal - changing my surname was a good chance to give them new ideas," says Rory, who met his wife Lucy on dating app Tinder four years ago.

Changing his surname to Lucy's wasn't a difficult decision for Rory to make. "I wasn't massively attached to the name Cook and it doesn't make any difference to me for work," he says. He didn't mind being the one to have to practise a new signature. "I thought it would be nice for us to have the same last name, and I think Dearlove is a better one."

Lucy, a radio producer, had already made clear that she had no intention of changing her name, like a growing number of British women. But she had expected Rory to keep his too.

"At first I thought he was joking," she says. "It wouldn't have mattered to me - he's entitled to keep his just as I am entitled to keep mine."

It did earn him kudos with her friends, though.

"They said it was really refreshing and really nice."

While the eight-year-olds took the news of Rory's new name in their stride, there were a few scoffs from the thirty-something men Rory plays football with. "That's weird," said one, casting him a funny look. "Modern men," said another, rolling his eyes. But that was about the extent of the criticism and Rory just shrugged it off.

'Another inequality in marriage'

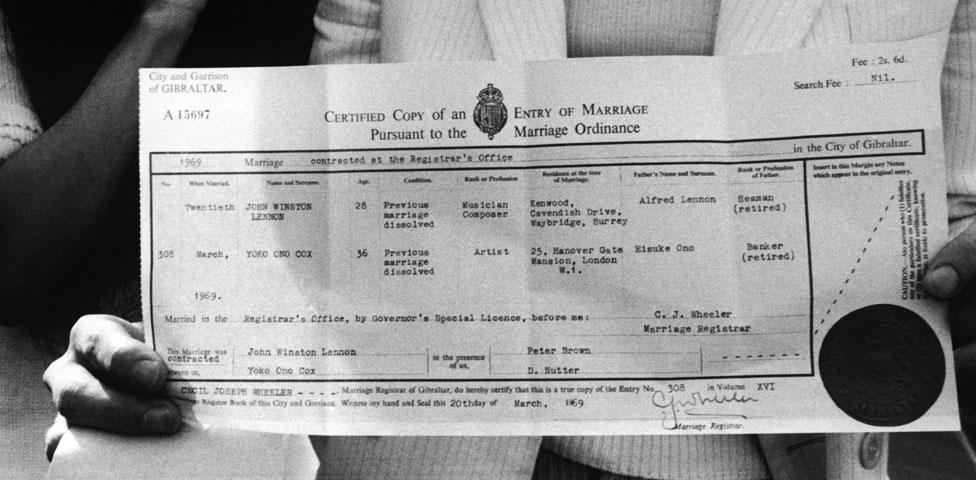

In England and Wales, marriage certificates list only the fathers of the couple getting married. There is no mention of the mothers. Some campaigners argue that the certificates aren't fit for modern times.

"It's a huge knock in the eye for mothers," said MP Frank Field, one of a cross-party group of MPs led by Caroline Spelman, which put forward a bill last year to include both parents.

In 2014, after legalising same-sex marriage, Prime Minister David Cameron pledged to address "another inequality in marriage which has not changed since the beginning of Queen Victoria's reign." MPs then tabled unsuccessful bills in 2015 and 2016.

The new bill has its second reading next month, external.

It can be a bigger problem, though. I know of one man whose parents refused to go to the wedding when they learned that their son would be taking his fiancee's surname. To them this was incomprehensible and proof that their son was a puppet controlled by his wife-to-be.

Rachael Robnett, a researcher at the University of Nevada, recently surveyed a cross-section of people in the US and UK and found that a man whose wife keeps her own surname is often viewed as "feminine".

"People gave traits with negative connotations like 'passive' and would say things like, 'She obviously wears the trousers,'" says Robnett. But people also gave more positive descriptors such as "nurturing" and "caring".

The woman in the relationship, on the other hand, was perceived to be less committed, ambitious, assertive and powerful.

While people are eager to push back on gender norms in some areas - the workplace, for example - there is still a strong adherence to tradition in romantic relationships, Robnett observes.

How would people perceive a man who took his wife's surname, I ask? "I'm very confident the findings I have got with this recent study would be exaggerated," she says.

Nonetheless, the signs are that the number of men taking their wife's name is increasing. A survey last year by Opinium of 2,000 UK adults for the London Mint suggested that one in 10 millennial men (18 to 34 years old) fell into this category. (It was impossible to find out how many male respondents were in this age group.)

Charlie Shaw, a Tibetan Buddhist meditation instructor, who took his wife's name when they married last year, says it's "ridiculous" that it's still assumed that women will take their husband's name.

"It wasn't a huge feminist statement but it was a gesture of allegiance - I took the opportunity to acknowledge that there is an unseen patriarchal bias and sexism in our society and that we can do things differently."

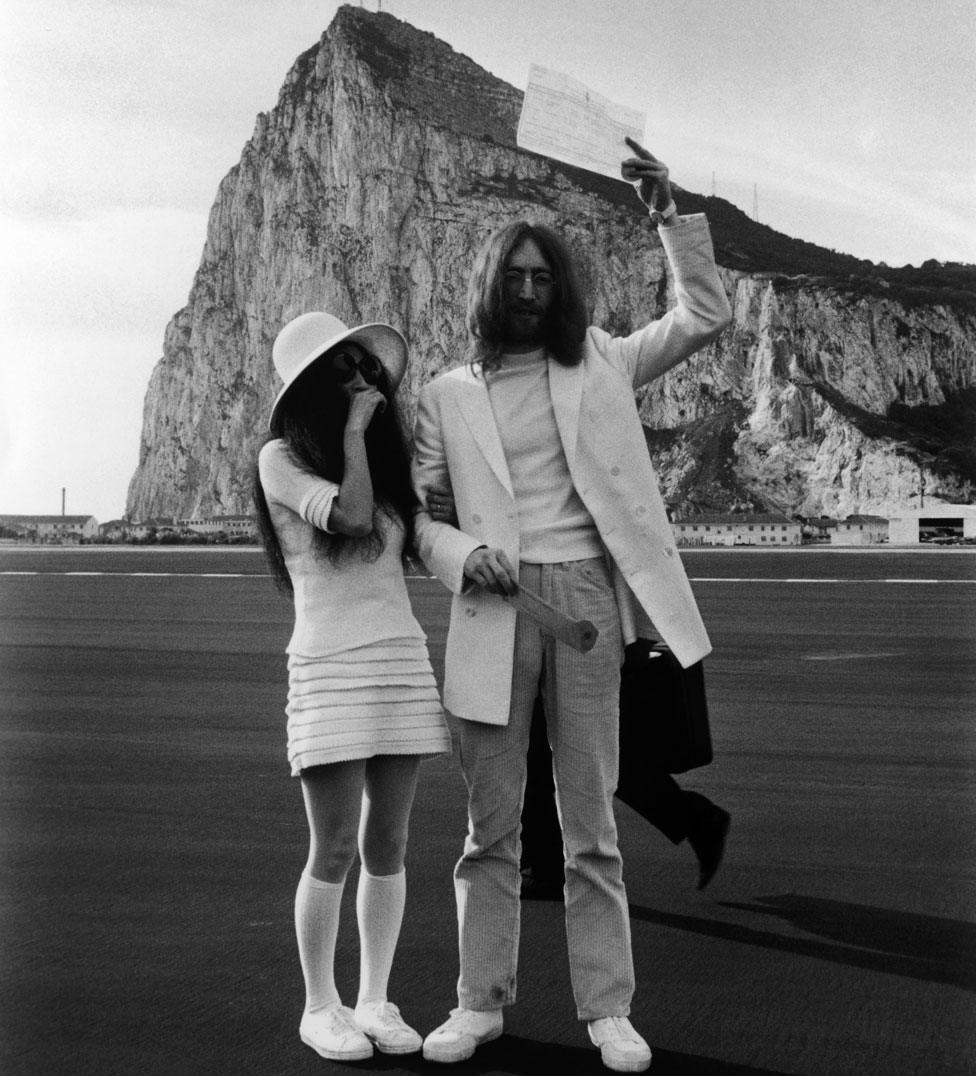

The moment at which Charlie Morley became Charlie Shaw (Photo: Millie Robson)

By coincidence, it wasn't the first time a man in his family had done this. Charlie's great-grandfather was Greek and his last name was Aspiotis - which prompted someone to throw a brick through his window in wartime London. He changed his name to his wife's - Morley - to be less conspicuous. Charlie continues to use Morley in a professional capacity.

Some grooms are embracing the chance to shed a paternal name with painful associations.

"Having his surname bothered me a lot and it never felt like mine," says 29-year-old Caio Langlois from São Bernardo do Campo in Brazil, who hasn't talked to his father for 10 years.

Caio was keen to shed his unmarried name and become Caio Langlois

Like Lucy Dearlove, Caio's wife, Jill, a Canadian journalist, had said she planned to keep her name after they married seven years ago, and Caio seized the chance to replace his unmarried name, Pereira, with hers.

"When we got married it was a great opportunity to take Jill's name and be myself as an adult," says Caio. "Jill is such an incredible woman and her name brings only positive, good references."

'One for both, both for each other'

Caio is a big fan of The Beatles and liked the idea that John Lennon and Yoko Ono took each other's last name as their middle name when they married.

"Yoko changed her name for me. I've changed mine for her. One for both, both for each other. She has a ring. I have a ring. It gives us nine 'O's between us, which is good luck. Ten would not be good luck," Lennon is reported to have said at the time.

Jill says many Brazilians would consider it a sign of weakness for a man to go against the country's macho traditions, but none of their friends and relatives questioned the decision.

"My masculinity is not in my name. Masculinity is based on your character, the respect you give to others and knowing who you are as a person," Caio explains.

"Sometimes people laugh when they know I changed my name, they tend to be quite shocked and ask why - but we are in the 21st Century, it's a new generation and we can do things differently."

The day after the wedding Caio says he woke up feeling different. "I felt relieved," he says. "I'd accomplished something that had bothered me for a long time."

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.