Escape from the asylum

- Published

In Croatia, thousands of people with mental illness live in institutions. The process of moving patients out of residential care and into the community happened decades ago in many European countries. But Croatia has resisted change - except in one region in the east of the country, close to the Serbian border.

The paint is peeling, the ceiling collapsing, and bright shafts of winter sunshine illuminate the dust that hangs mid-air. In the closed, and now abandoned, asylum of Cepin, rooms open off a very long corridor.

"When we were waiting for our medication, we would squat here in this corridor until the nurse came to give us our pills. There were no chairs," says Branka Reljan, who has schizophrenia and lived here for 12 years.

She is taking a trip down memory lane with her partner. Drazenko Tevelli was institutionalised after developing mental illness as a result of alcoholism. In Cepin, the couple conducted their romance in secret - this is the first time they have been back since they moved out in 2014.

In the room Branka occupied with three other women, a label with her name is still visible on the cupboard where she kept her few personal effects. Her bed is still here too with its hard, grubby mattress.

"It was a comfortable bed - good for my spine," says Branka, surprisingly perhaps. "I was lucky - there were no cockroaches."

Branka and Drazenko outside the Cepin asylum, now closed

Drazenko was not so fortunate.

"Cockroaches would creep on to my forehead during the night and bite me. So I always had blood on my pillow," he says.

Drazenko became depressed and suicidal during his 13 years living in Cepin. In his old room, he points to the water pipes that run along the top of the window.

"I thought I would end my life by hanging myself from those pipes. I spent so many years here - I thought I'd never get out."

Few people did.

"Nobody in the centre was cured and went back home - it was like a life imprisonment," says Branka.

But three years ago, the couple's incarceration did finally end. Like dozens of other former residents, Branka and Drazenko started a new life in a shared flat in the nearby city of Osijek. The asylum closed.

"On that occasion we released 100 white pigeons from their cages," says Ladislav Lamza, the driving force behind the decision to move people out of the centre in Cepin and into the community.

"Usually people celebrate when they open an institution, but we celebrated when we closed it!"

Lamza had been a social worker for 20 years when a professional visit to Austria changed his mind about people with serious mental illness.

"I saw that recovery is possible," he says. In Austria, he visited people living in supported accommodation - he could not tell who was a worker, and who a beneficiary.

Back in Croatia, where he was director of residential institutions in Cepin and the nearby city of Osijek, he determined to follow the Austrian model.

"It's very easy," he says. "If we put people in human conditions they become more human. If we put them in inhuman, confined conditions, they become less human."

Ladislav Lamza: Community-based care is cheaper than keeping a person in an institution

Lamza began the process of de-institutionalisation five years ago. In Osijek, he procured empty apartments from the local authority. But he had to persuade the residents of both centres, some of whom had been there for decades, that life would be better if they moved out.

"They said, 'No, we feel secure in the institution, we have everything here.' I said, 'OK, but just try and live in the community for a few days to see what it's like.'"

When Lamza told them that they would not have to share one television remote-control among so many people because they would be living with only two or three others, that gave some of them the motivation they needed.

Find out more

Listen to Escape from Croatia's Asylums on Assignment, on the BBC World Service

For transmission times or to catch up online, click here

Often, it was just as big a change for Lamza's staff. They were no longer simply cooks, cleaners and janitors in an institution. In the apartments they took on the role of psycho-social support, helping people with household tasks and accompanying them on outings.

Branka and Drazenko have lived together in an apartment in Osijek with flatmates for three years.

"On our first day there, we went with our assistant to the supermarket," says Branka.

"We chose expensive salami and mayonnaise - things we hadn't had for 12 years. When we brought all this stuff back to the flat, we were all immediately feeling better. I felt like a free person again. On that first night, I slept very well."

'I am not too different from other people'

Now the couple share their own twin room. They like to ride the bus to meet friends for coffee, read and make cigarettes - they are both incorrigible smokers, a hangover from so many years spent in an institution. And they regularly visit what was formerly known as the Home for Mentally Ill Adults in Osijek - the other institution Ladislav Lamza moved people out of.

It is a large, two-storey building inside a walled compound. When Osijek was under massive bombardment during the war of the 1990s, 250 people - residents and staff - spent three terrifying months sheltering in its basement. The walls remain pockmarked from artillery fire.

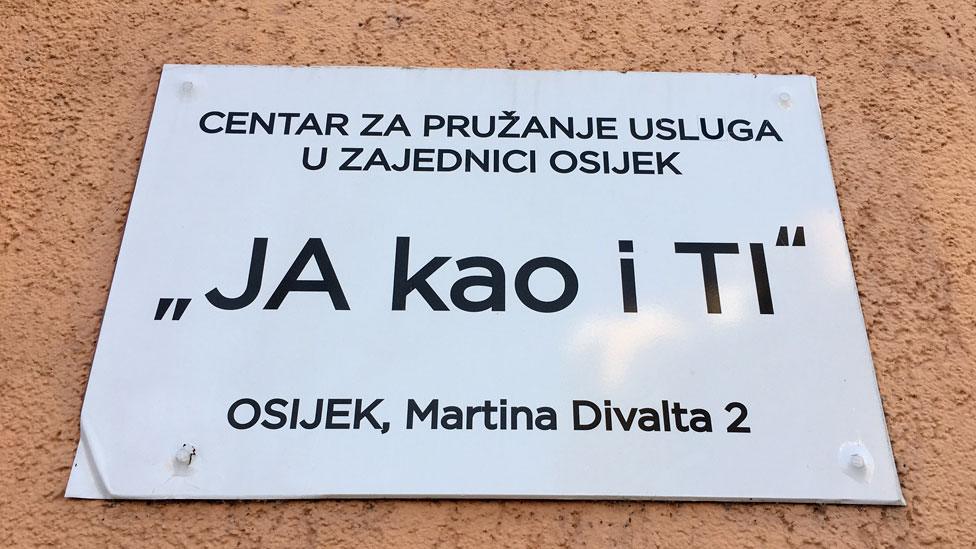

In 2015, Ladislav Lamza changed the institution's name to the I'm Just Like You Centre, an attempt to underline the humanity of those who live with mental illness.

The Home for Mentally Ill Adults is now the I'm Just Like You centre

It still has some residents - 27 people who need round-the-clock care. There are also a few bedrooms where people may stay temporarily if they have a crisis at home. But largely the centre functions as a community hub. There is a café and workshops, a laundry and greenhouses - all staffed by former residents, many of whom struggle to find paid employment elsewhere.

Tatijana Ilic, who works in the laundry and sewing department, was first forced into a psychiatric hospital by her husband when she was in her 20s.

"I was released after a month and a half," she says. "The doctor said to my husband, 'She's not crazy, she's just rude.'"

Even so, Tatijana spent more than two decades on heavy medication, in and out of residential homes and psychiatric hospital. She has seen and experienced some terrible things. In one institution, women were tied to the staircase if they stepped out of line. In another, none of the residents were allowed underwear and they were forced to line up naked in the hall to queue for the shower.

Tatijana lived in Cepin for seven years until she moved into a flat in Osijek as part of the de-institutionalisation process. She and her flatmates are independent now - a household no longer needing an assistant to come in daily to help and support them. That, says Ladislav Lamza, means a financial saving.

Tatijana dreams of having her own flat, where her daughter and granddaughter can come to stay

"If we work in a proper way, people become more independent, so they need less help from an assistant. So, community-based care is cheaper than keeping a person in an institution - by more than 100 euros a month."

In Croatia, part of the debate around de-institutionalisation is about cost. Recognising the initial expenses incurred in the process, the European Union has allocated Croatia 100 million euros to help re-house people held in mental institutions. But there has been little take-up - of the country's 28 residential facilities for people with mental illness, only in Osijek and Cepin has wholesale de-institutionalisation become a reality.

Tatijana dreams of having her own flat - somewhere her daughter and granddaughter can come and stay. That is unlikely unless she secures employment outside the centre. Meanwhile life is pretty good.

"I feel healthy. And I'm happy because I'm busy," she says.

She still takes some medication, and she keeps 5mg of diazepam, a tranquilliser, in case she has an emergency and feels stressed or unwell.

"But I can't remember the last time I had to take it," she says.

Marta Gasparovic, Tatijana's psychiatrist, has noticed significant changes in her patients since they moved to flats in the city.

"Before we spoke mostly about medication - is the patient co-operative, do they cause problems? Now, they're more fulfilled and satisfied. And there's much more to talk about.

"For example, I had a patient who started a new emotional relationship, and his medication was affecting his sexual functioning. So he asked me if we could change it - that's something new in his life."

However, she believes some patients struggle in their new environment.

When that happens, she recommends that person moves back into an institution. She has done that twice since 2014.

And there are still crises. One member of staff is on sick leave after an altercation in one of the flats.

"The assistant says this young man had a knife in his hand and approached her - those are her words. Nothing happened, but she was very afraid," says Lamza. "He's currently living here at the centre. It's one of two serious incidents we've had in the flats in the last five years."

In a conservative society like Croatia, where mentally ill people may be seen as dangerous maniacs, these kinds of events will not inspire confidence in de-institutionalisation. But Lamza says violence was much more frequent before.

"Maybe there were three or four cases a year of heavy incidents - violence with knives, between beneficiaries, and also involving workers. The less serious incidents like pushing or yelling or quarrelling - that happened almost daily."

In December, former residents of the institutions of Cepin and Osijek testified at a round-table meeting in Croatia's parliament in Zagreb about how their lives have changed since they moved into the community.

Ivica (left), Tatijana (centre), Ladislav Lamza (back right) and the two other speakers at the Croatian parliament

It was organised by the Ombudswoman's Office for people with Disabilities - in an effort to galvanise politicians to follow eastern Croatia's example. The meeting was attended by staff and residents of institutions, MPs, and the government minister responsible.

Ivica Ducek was one of those from Osijek who spoke at the meeting. The room fell completely silent as he described the desperation he felt, and a suicide attempt he made when he lived in Cepin. Now, Ivica told them, he lives with his girlfriend, Mihaela, and a flatmate, and they enjoy a great relationship with their neighbours. His next plan, he said, was to regain legal capacity, so that he will be allowed to make his own decisions about his life.

"All of us are birds," Ivica told the assembled gathering. "It's just that some of us have broken wings."

Listen to Assigment: Escape from Croatia's Asylums

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.