Black Panther: 'Why black people like me are refusing to be sub-plots'

- Published

The much-anticipated film version of Black Panther, one of the only black Marvel superheroes, is about to be released. It's a moment of special significance for black comic fans, who have only rarely seen a hero on the page who looks like them, and almost never on screen. Here, British graphic illustrator Jacob V Joyce explains the importance of the groundbreaking character.

Like many children, my imagination came alive through the adventures of cartoon heroes and villains. I learned to read by closely examining the illustrated escapades of Spider-Man, Batman and any other comic book stories I could get my hands on.

Yet, as a black child, these characters looked nothing like me.

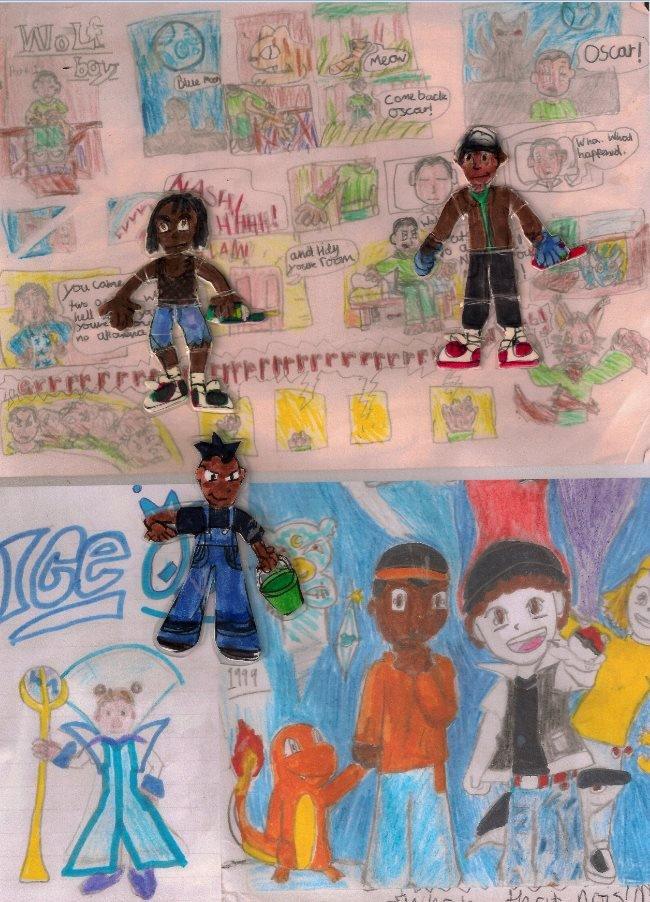

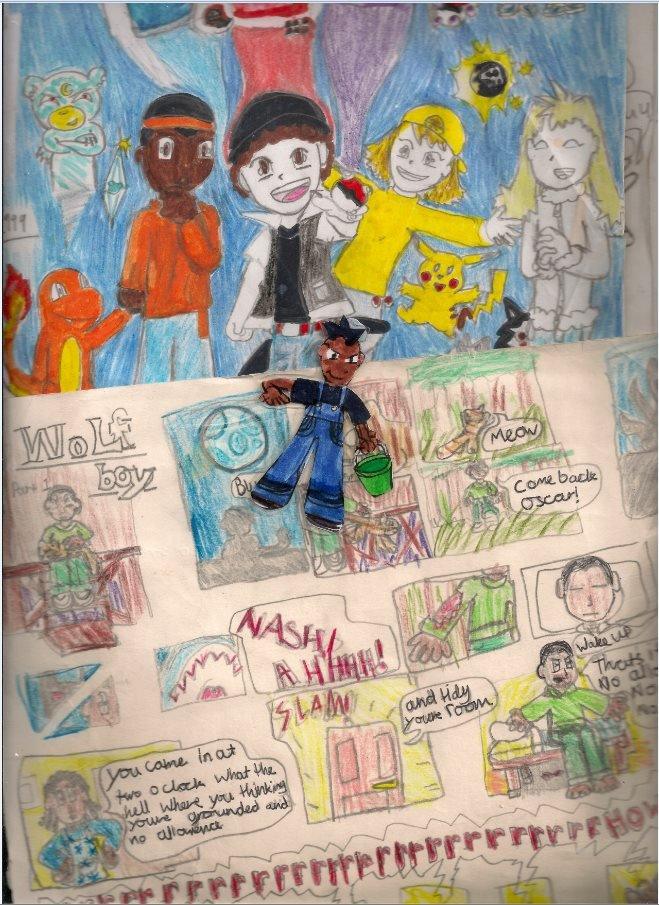

So I took matters into my own hands. At the age of eight I began drawing black and brown versions of these heroes. By creating my own characters and my own mini-comics, I fashioned a world that I could imagine myself existing in.

Jacob's early cartoons

For my 11th birthday I begged my mum for a laminator. You might think this was a curious gift for a child, but I was overjoyed. I started to coat the army of small cut-out paper characters I had drawn in protective plastic, and turned them into two-dimensional action figures.

I wanted to protect these small fantastical representations of myself, which seemed to be missing from the world around me.

Black Panther, and the handful of other comic book characters of African and Caribbean descent, did not appear on my radar until I was a teenager. By then, my desire for black narratives had led me to look beyond the mainstream comics and their Hollywood depictions.

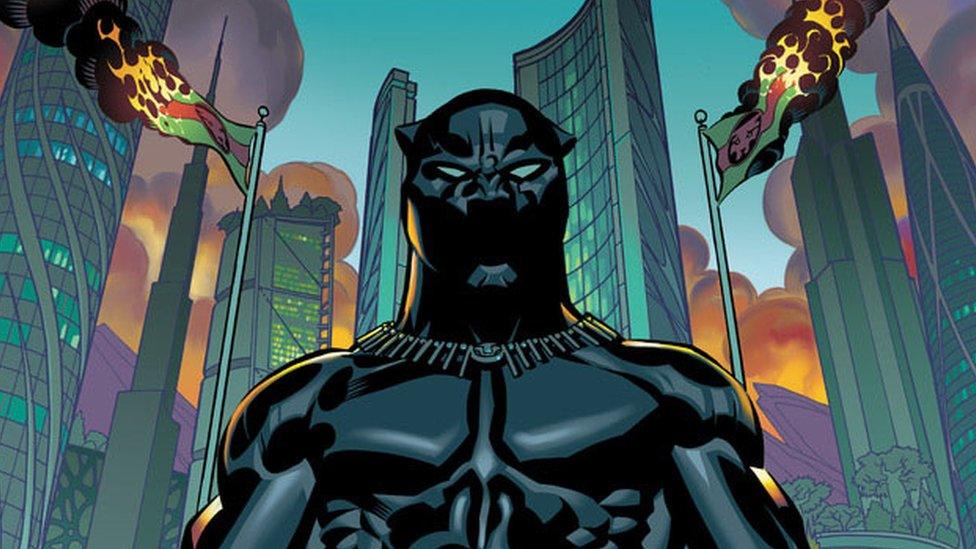

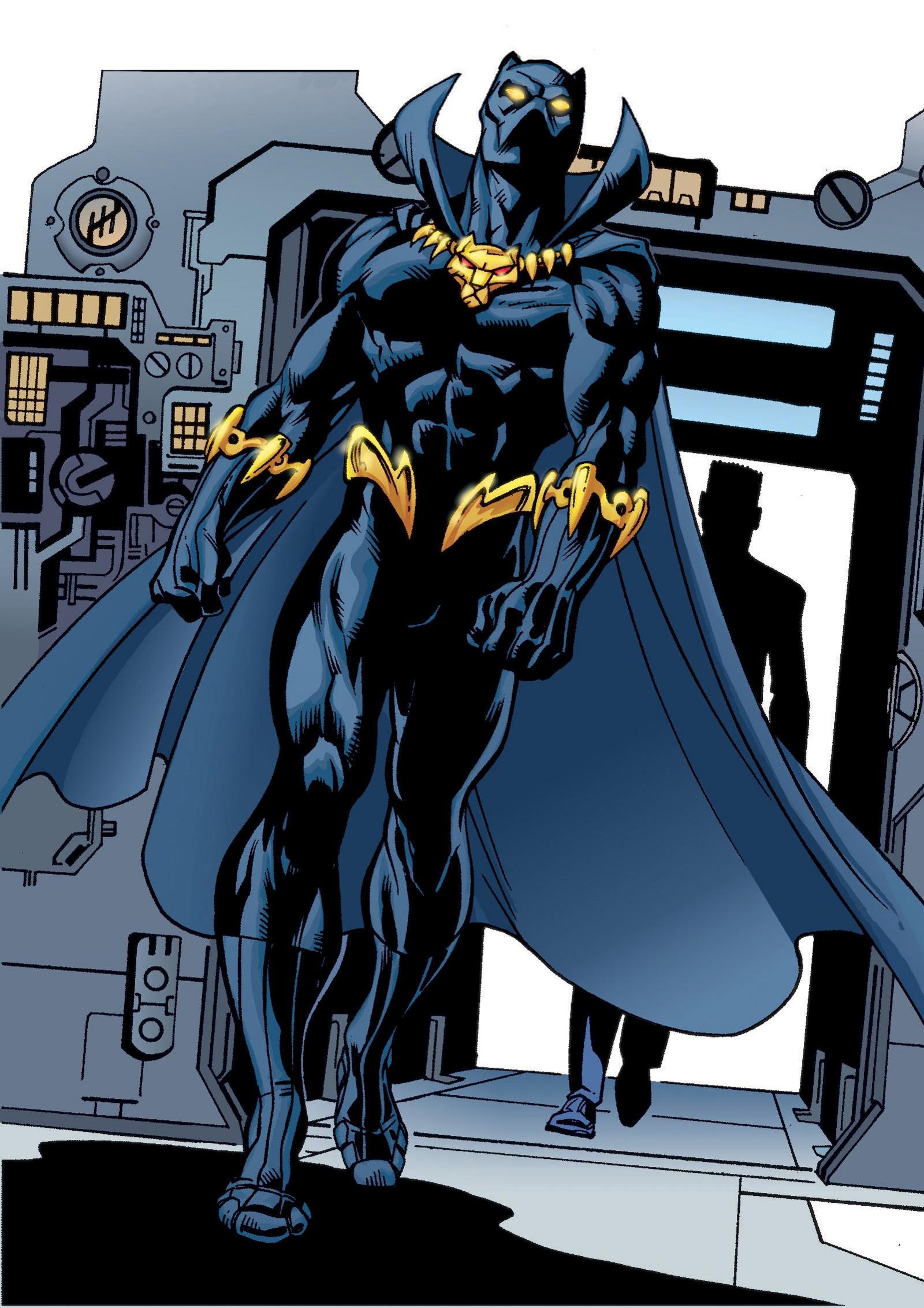

The character is a sight to behold.

Clad in distinctive bullet-proof black armour, usually capeless but with a full facemask, Black Panther - or T'Challa - is the king and protector of the fictional African nation of Wakanda.

A true warrior, he's a master tactician with genius intellect, rigorous martial arts skills and superhuman strength.

You can imagine, as a teenage comic book fan unable to find any black figures that were more than side-kicks, the thrill I felt when I first came across him.

But if T'Challa was something to be excited by, his kingdom was a wonder beyond my wildest dreams.

Wakanda, an advanced technological nation, is untouched by colonialism. In some versions, the country is hidden behind a giant wall, undetected by maps. With flying cars and futuristic skyscrapers, its technological sophistication makes it impenetrable. The country's wealth comes from mining a metal called Vibranium - used to make Captain America's shield.

For me, this fictitious land represented a Pan-African dream, free from the painful history of slavery. It is the story of an African nation that has evaded colonial plunder and managed to focus all of its resources on its own development and technological advancement. This rewriting or reclamation of black history is an extension of Afrofuturism - a cultural philosophy pioneered by jazz legend Sun Ra and countless artists and musicians since.

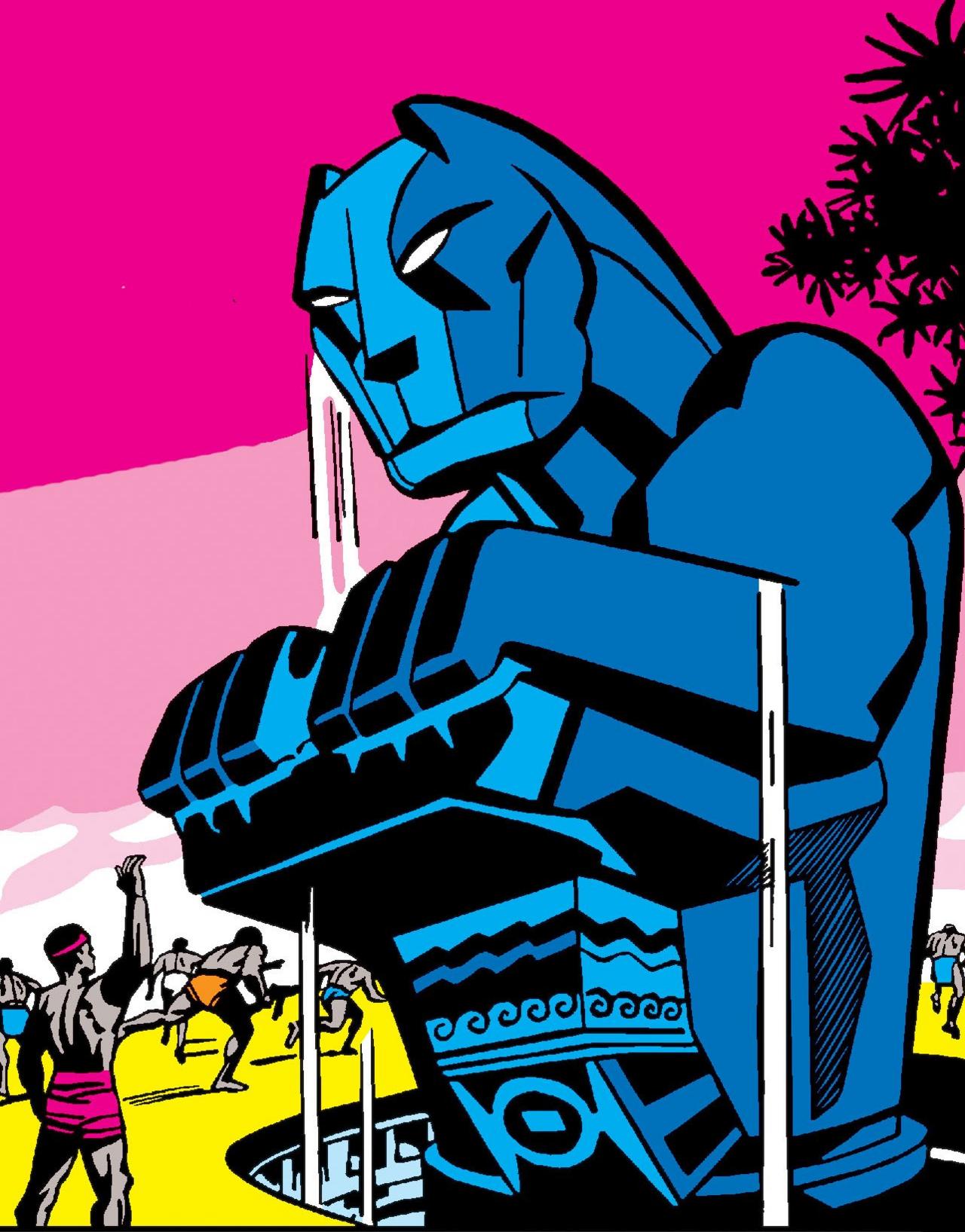

To avoid detection, Wakanda appears an impoverished nation to the outside world

Fast-forward 20 years to today, and the mainstream world of comic book superheroes and their blockbuster movie adaptations has not changed much.

Aside from a handful of characters, like my personal favourite, Storm from X-Men, it's rare to see black superheroes take centre-stage on screen - they usually act as devices to propel the story of the white protagonist further, with little-to-no speaking lines.

What's even worse is watching black superheroes being introduced for a brief moment only to be the first to die. I know many Marvel fans are still mad about Darwin, an African-American mutant whose body can adapt to survive anything, being killed off within minutes of his introduction in the 2011 movie X-Men First Class.

Black Panther made an appearance in Captain America: Civil War (2016)

It may seem petty to grieve over fictional characters, but when you have been waiting for two decades to see black superheroes in action, it can be hard to remain patient.

Black Panther offers us an opportunity to imagine a different kind of hero.

The world of the Black Panther

The Black Panther was created in July 1966, two months before the founding of the Black Panther Party.

The X-Men mutant Storm is the love interest to Black Panther in the Marvel Comics. However, this angle will not be explored in the 2018 film because image rights of each character is held by different studios.

Women in Wakanda have powerful positions in the Kingdom. The Dora Milaje are the all-female personal bodyguards of the Black Panther.

Two of these warriors, in later editions of the comic, were applauded by the LGBTQI community for being in an openly lesbian relationship.

A new Black Panther series written by Ta-Nehisi Coates and drawn by Brian Stelfreeze was launched in 2016 and continues to be published with Coates as the head writer.

For black comic book geeks like myself, and for thousands of black and brown action movie fans across the world, the imminent release of the Black Panther movie represents a shift in focus that has been a long time coming.

The film, which stars Chadwick Boseman and Lupita Nyong'o, is still to hit theatres but advanced ticket sales are outpacing every other superhero film to date.

Here in the UK every black person I know is either excited about or at the very least aware that the Black Panther is coming. Memes are circulating about the outfits people are planning to wear to the cinema and regardless of whether it fulfils our expectations, it is an important historical moment for us.

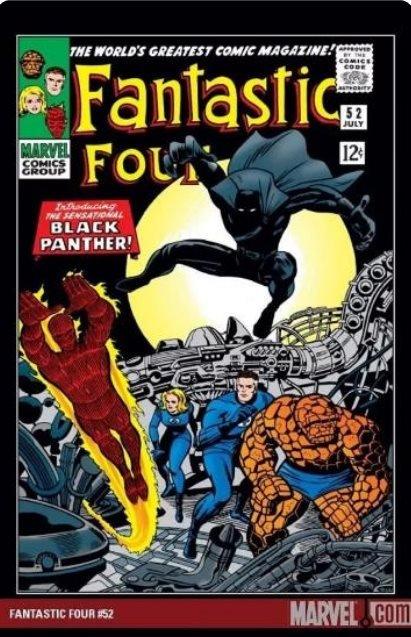

The original 1966 Fantastic Four cover in which Black Panther makes his debut

Speaking to the website Mother Jones, the film's co-writer Joe Robert Cole explained the importance of bringing the story to the screen: "Black Panther is a historic opportunity to be a part of something important and special, particularly at a time when African-Americans are affirming their identities while dealing with vilification and dehumanisation.

"The image of a black hero on this scale is just really exciting," he adds.

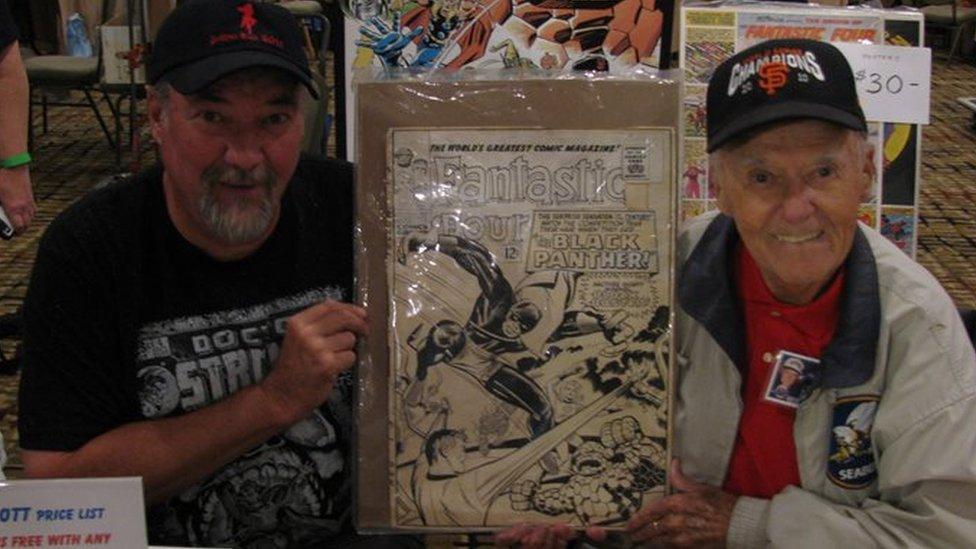

Joe Sinnott (right) and his son Mark

Ironically, Black Panther started life as a subplot in the Fantastic Four series - and none of its creators were black. Writer-editor Stan Lee and writer-artist Jack Kirby introduced the character in April 1966.

Joe Sinnott was an inker on Fantastic Four at the time - he knew he was working on something special when bringing Wakanda to life.

"What a beautiful nation - the landscape, creatures, jungle, the people. One of the world's most technically advanced nations. It had it all," he says.

The Dora Milaje, the female warriors of Wakanda, "move as one" when they fight

Despite rumours to the contrary, Black Panther wasn't inspired by, or named after, the Black Panther movement that came in 1966. The comic predated the political group. There was even a brief period when Marvel changed the character's name to Black Leopard, but once it became evident that fans were not associating the character with the political movement, they reverted to the original name.

Sinnott wasn't really aware of the popularity of the Black Panther in 1966.

"At that time there weren't comic conventions to attend so I personally didn't hear from the fans as you would today." But, he adds, "I would think that the letters to the editor must have been overwhelmingly supportive."

The issue sold well and by the 1970s Black Panther was a protagonist in his own comic book.

The film's costume designer Ruth E Carter cites African tribes' clothing as an influence

A new Black Panther series written by the award-winning journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates and drawn by Brian Stelfreeze was launched in 2016. Coates portrays him as a conflicted king attempting to balance the traditions of his culture with his people's demands for democracy.

I've asked myself whether the film's release truly signals a new frontier for black superheroes in cinema. For years Hollywood has worked of the assumption that black-led films wouldn't translate to ticket sales. This was disproved when Jordan Peele's 2017 spine-chilling horror movie Get Out grossed over £180 million ($255 million) globally.

The myth that films with black leads only appeal to niche markets no longer holds true.

On Marvel's Netflix channel, a black superhero called Luke Cage has been given a series of his own. Rivals DC Comics have also just released a Netflix series called Black Lightning, with an almost all black cast.

These may be small steps, and a long time coming, but things are moving in the right direction. I'd like to think that the visibility of this story will inspire a new generation of activists, artists and communities to keep building the worlds they want to see.

And maybe black children won't need to ask their mothers for laminators in order to create a world where they can be heroes.

You can see more of Jacob V Joyce's work on jacobvjoyce.com

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.