'I tried to kill myself nine times before the NHS helped me'

- Published

Sherry is now back home with her family and making plans for the future

It was the ninth time in the space of 10 days that Sherry Denness had tried to kill herself. "It felt like checkmate - there were no open doors or other ways for my life to turn, I just wanted to die," she says.

Only just 18, Sherry has been diagnosed with a number of mental health conditions, including borderline personality disorder (BPD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

On seven of her nine suicide attempts, which took place in November last year, the teenager had landed in A&E, been patched up and deemed well enough to be sent home with no further help. Another time she'd taken all of her prescribed medication in one go and ended up in critical care for two days. But once the physical symptoms had been dealt with, to her parent's despair, she was simply discharged and sent home.

This time things turned out differently.

"When you're in mental health crisis, it feels like everything is just closing in on your brain like a clamp," she says.

"I was psychotic and I was hearing Kieran in my head telling me I need to leave the house." Kieran is one of the voices Sherry hears - the worst one, she says.

"When I'm in that state, it is very hard to comprehend that the voices are not real. I hear him in my ears like I'd hear a real person. He will say, 'No-one likes you, no-one loves you, you're better off dead.'"

Under Kieran's influence, she quarrelled with her parents and stormed out of the house. A little later PC Pete Coe and PC Dan Ayrton found her on a pathway nearby, train tracks lying just ahead. They'd been alerted by a crisis team Sherry had called in her non-lucid state to ask about a place to live.

Sherry in hospital recovering from an overdose

"It was a freezing cold evening and Sherry was sitting cross-legged on the floor, I remember there being a lot of blood because she was self-harming," says Coe. Sherry's clothes were scuffed from her attempts to scale the fence that stood between her and the train tracks.

After checking with a mental health professional at the local hospital, Coe used his police powers to detain Sherry under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act. "By sectioning Sherry we were able to do what we could to keep her safe and get her the help she clearly needed," Coe says. At the time, Sherry didn't want to go with the police and resisted their attempts to help her. But now she thanks them for calming her down - and, she says, for saving her life.

When Sherry's mum, Andi, saw the blue lights of an ambulance from her kitchen, a cold tentacle of dread slipped around her stomach. She ran out of the house, fearing the worst. To see her daughter alive, and with the police, was a huge relief.

Sherry with Andi

"When they told me they'd sectioned my daughter, I felt my legs go from beneath me and I cried like a two-year-old child because I was so grateful that she was finally going to get into hospital and get the help she so desperately needed," she explains. "Sherry is from a very loving family but she wasn't well so she hurt herself again, and again, and again. And each time they discharged her we were saying as parents, 'She needs to be in a hospital - she's not very well.'"

But things didn't go smoothly even after she was sectioned. Once she'd been escorted by the police to A&E to treat her physical injuries she should have been transferred to a children's mental health unit.

But a shortage of beds meant Sherry landed in an adult ward at a hospital in Guildford, where her parents say she was propositioned by a male patient in his 50s. So she was then transferred to a secure children's mental health unit in Sheffield, 160 miles away. It was the only place that was available.

Sherry as a young child

She was eventually transferred from Sheffield to another hospital in Guildford, close to her home, and there she began to feel more lucid and positive. She was discharged at the end of November and is now back at home with her family.

Sherry has spent nearly a year of her life in mental health facilities.

She was 11 when she was first assessed by the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (Camhs). "They took my mum aside and told her I was just an attention seeker and they didn't take it seriously," she remembers. Eventually, at 13, she was given treatment for ADHD, but by then children at her school had already begun to bully her.

Sherry before she left school

At school, Sherry was often kicked out of class for disruptive behaviour and spent most of her time in isolation. "I couldn't concentrate and no-one listened to what I was saying," she says. "When you have ADHD it feels like everything is going 10 million times faster than normal and you don't understand why people around you are so calm." Sherry struggled to make friends and became increasingly isolated. She began self-harming at 13 and was first sectioned by the police at 14. At that point Sherry's parents decided to take her out of school.

The family feels Camhs has let Sherry down for years now.

After she was finally sectioned in November her parents made a viral video in which her dad, Chris, tells the story of those horrific 10 days by holding up a series of messages drawn on paper. He then asks people to show they care about her - and about other young people struggling to get treatment for mental health problems - by getting involved in a social media campaign under the hashtag #wecaresherry.

We care Sherry - her parents' campaign

"We started the campaign to give Sherry hope because she thought that nobody cared," Chris says. But the family are also calling for changes in the way Camhs operates.

For example, they argue that A&E is no place for a child having a mental health episode - though that is where Camhs advises them to go.

"Getting Sherry to A&E when she's in a heightened state is a nightmare," says Chris. "Normally we have to call the police to get her there." Both parents have been trained in safe restraint but have to take shifts because her physical strength when she is distressed can be overpowering.

Sherry and her father, Chris, on a family holiday

They tell me about six-hour waits, unsympathetic security staff and receptionists who are openly exasperated at seeing Sherry back in A&E again.

"I have been to A&E a lot of times for self-harm and suicide attempts and parents of little kids will look at you in disgust and shuffle their kids away because they can see you're holding your arm or your leg," Sherry says. "It's not nice and it makes you feel even worse. You sit there for hours and hours until they can get a Camhs person to come and see you."

In the 10 days that Sherry attempted to kill herself nine times, she was seen by 18 different healthcare professionals, ranging from staff from A&E to Camhs. But none provided the help she needed to address the cause of her problems. The family says the threshold for accessing this help is too high.

They are also calling for more investment in Camhs and better training for the staff young people experiencing a mental health crisis might come into contact with, including teachers, the police, paramedics and A&E doctors and nurses. They'd also like to get the message out that early intervention is key.

"A lot of this could have been avoided if I'd got the help I needed sooner," says Sherry.

Where to get help

YoungMinds Parents Helpline 0808 802 5544 or click here , external

Call the Samaritans, external on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org

24-hour NHS support line on 0800 0234 650 - or click here, external

The family has received hundreds of messages of support from parents and young people who say they have had experiences similar to Sherry's. The video, meanwhile, has now been watched more than five million times.

In it, recordings of Sherry playing her digital piano can be heard in the background. When she is at home she tries to play every day - it gives her a focus.

"Whenever Sherry is in hospital I sit and listen to her piano recordings. And then I look over and I realise she's not there, but it still brings me comfort," says Andi.

At the same time, if Sherry is in hospital she will be wearing a pair of new pyjamas, handmade by her mum, who is a dressmaker. "I wear the pyjamas and hug myself in them," Sherry says.

She also has a fleece "care blanket" with photos of her loved ones printed on it, which she wraps around her shoulders.

"In many areas it is desperately hard for young people to get the support they need," says Matt Blow, policy manager at YoungMinds, a UK charity for the well-being and mental health of young people. Every day the charity's helpline hears from parents who have been waiting months for an appointment for their child and have nowhere to turn, he says.

"Sometimes their children have started to self-harm, become suicidal or dropped out of school during the wait."

He estimates that only one in four children with mental health problems is currently receiving support from Camhs, but adds there is a postcode lottery, with services far better in some parts of the country than others.

A recent Care Quality Commission (CQC) report, external - ordered by the government as part of its Five Year Forward View for Mental Health, external, a £1bn plan to improve mental health care by 2021 - says some children are waiting up to 18 months to be treated.

It also echoes Sherry's family's concern that those who work with children and young people - in schools, GP practices and A&E, for example - sometimes lack the skills to identify and support children with mental health needs, hindering their access to specialist help.

According to another independent report, external, Camhs turns away nearly a quarter of children referred to them for treatment by concerned parents, GPs and others.

"Without a doubt, after years of drought, the NHS's mental health funding taps have now been turned on," Claire Murdoch, Mental Health Director for NHS England said in a statement when the CQC report was published. "It's going to to take years of concerted practical effort to solve these service gaps - even with new money - given the time it inescapably takes to train the extra child psychiatrists, therapists and nurses required."

Asked to comment on Sherry's story and the shortcomings highlighted by the CQC, she said Camhs services were improving "but from a starting point of historic underfunding and legacy understaffing, relative to rapidly growing need".

She added: "The CQC rightly acknowledge that the NHS's five-year plan for mental health, developed with patients, their families, health professionals and other partners, sets out a clear route map for improvement and investment, and progress is under way. As we look out over the next few years, the CQC is also right to highlight better cross-sector working involving health providers, schools, regulators and government, as well as children and parents, if we're to put in place care which is timely, supportive and of the highest quality."

As the NHS struggles to cope with demand, police forces across the country have reported a rise in the number of mental health related incidents they deal with. The Metropolitan Police, Britain's biggest police force, received a phone call relating to mental health every five minutes last year. The numbers have risen by nearly a third since 2011-12 and are now at record levels.

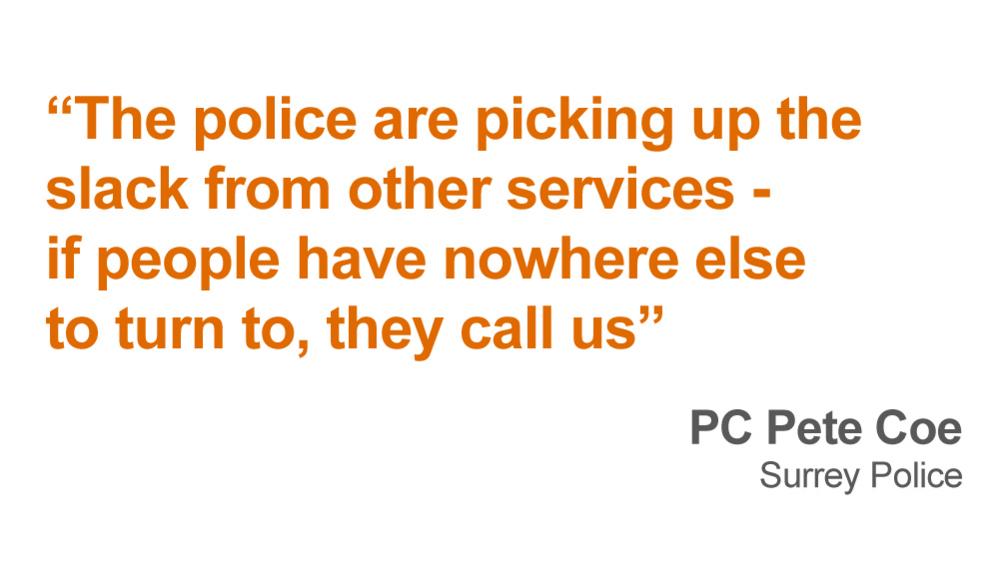

PC Coe, who found Sherry near the railway tracks, says that even in his three-and-a-half years in the job, the amount of time he spends dealing with mental health calls has noticeably increased. "The police are picking up the slack from other services," he says. "If people have nowhere else to turn to, they call us."

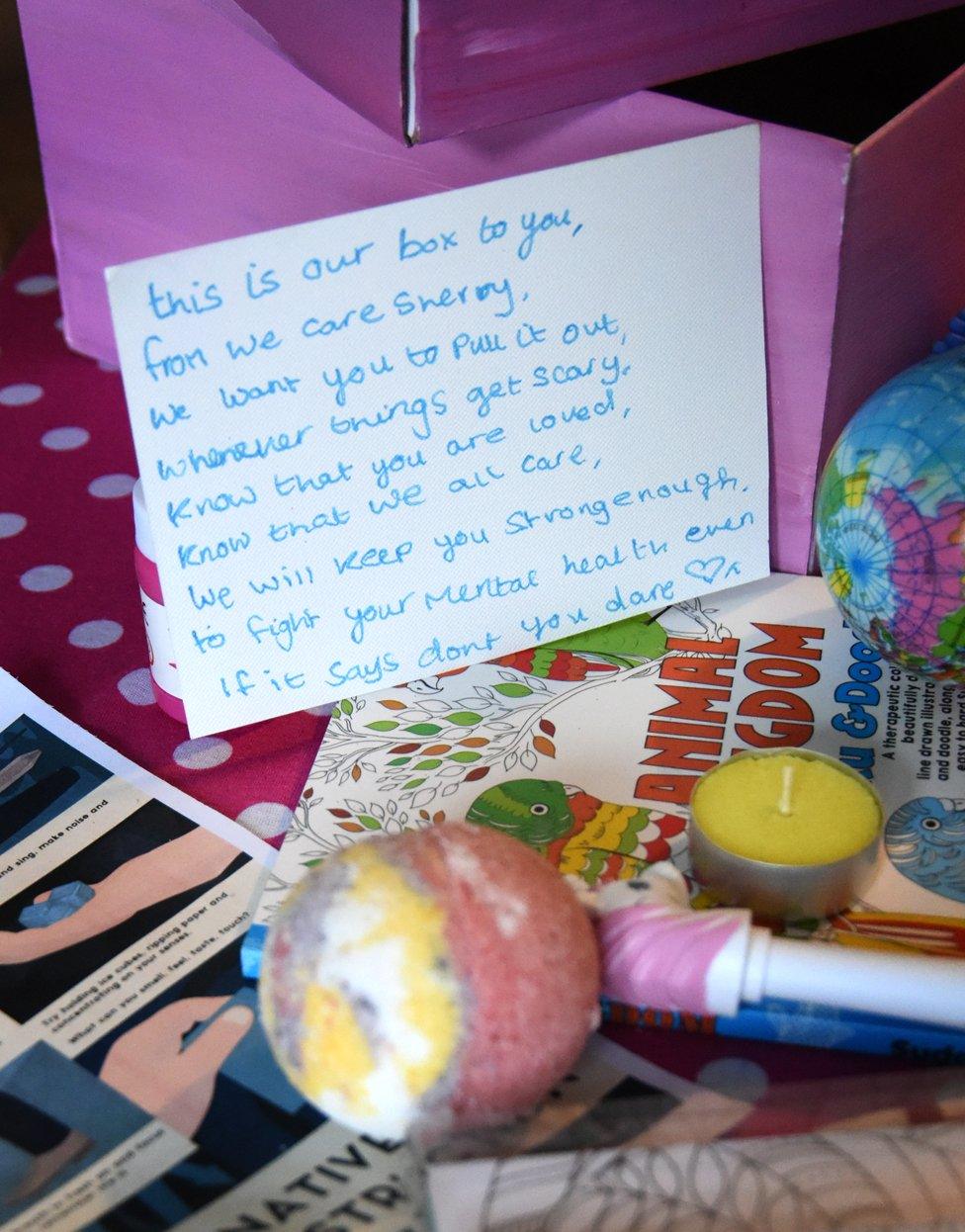

It's been more than three months since Sherry came out of hospital and, buoyed by the #wecaresherry campaign, she's begun to make recovery boxes for other young people struggling with their mental health. The boxes include home comforts like fluffy socks and chocolate, as well as stress toys and advice on coping techniques. Sherry received her own recovery box just after coming out of hospital and her favourite items include "an unsquishable stress ball" and coconut hand cream, because it smells like holidays.

"When I'm low I find it really lonely and I deny myself nice things like this because I think I'm helping myself by punishing myself. So if someone goes out of their way to send a box like this it is really lovely," Sherry says.

She loves helping people and wants to be a police officer for that reason. She explained this to PC Coe and his colleague over the course of the hours they spent together waiting in A&E, and then waiting for Sherry to be transferred.

"It was good to hear that Sherry had plans for the future," says Coe. "She asked if a police career would be possible after all her run-ins with the police, she was worried about being black-balled because of it."

He reassured her that she hadn't done anything wrong - being sectioned wasn't the same as being arrested. It was something that "could happen to anyone".

Sherry's ambition to join the police may seem surprising for someone who has had so many traumatic experiences involving them.

"I have been resuscitated by the police, I have been detained and sectioned by the police and they've stopped me from doing things I was determined to do," she says. "But I think they are highly underrated and they deserve a lot more respect. There are people my age who call them pigs - but I think they do a brilliant job."

Sherry says her dog, Ruby, has a calming influence

For now, Sherry is focusing on getting better and supporting other people in the process.

"I still have my low days and I still struggle but it is more bearable - it is never going to go away and I've had to come to terms with that. There will be days throughout my life when I'm not going to want to be alive, and I have come to terms with that as well," she says.

She draws strength from the huge support for the #wecaresherry campaign.

"I am just taking things one day at a time and knowing that there are people out there who are supporting me really brings home the fact that I do deserve to be alive. It really is amazing."

You may also like:

12 tips on what to pack for a mental health hospital

What to pack if you’re going into a mental health unit

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external