'My periods made me suicidal so I had a hysterectomy at 28'

- Published

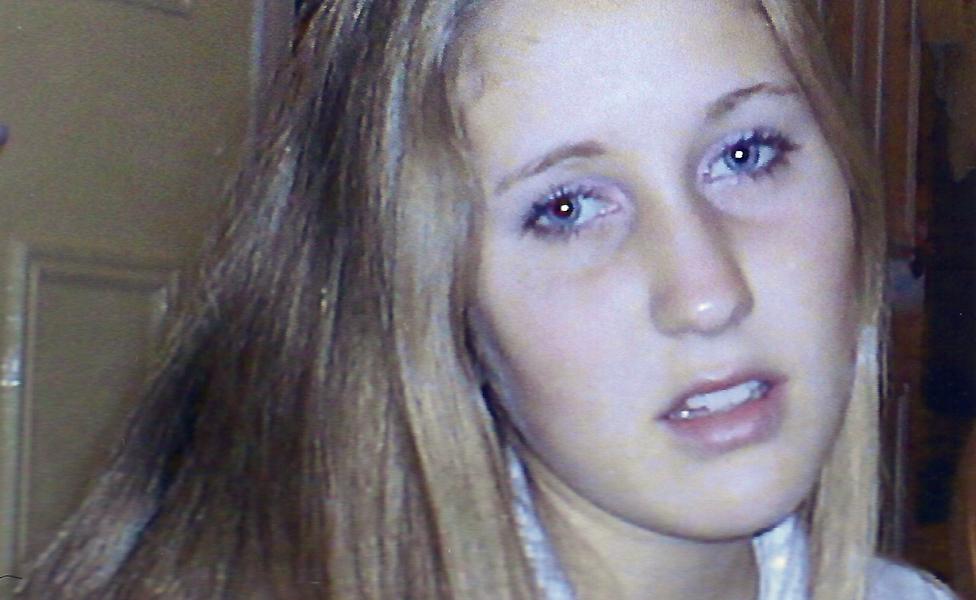

For a couple of weeks every month, Lucie seemed to become a different person - one suffering from countless mental and physical problems - and she couldn't understand why. She spent years looking for a doctor who could provide an answer, and it took a hysterectomy at the age of 28 to cure her.

"I would know that things would change before I even opened my eyes in the morning. It was just like this weight had been put on me," says Lucie. "I did go to the doctor at one point and tell them that I thought I was possessed."

Before puberty hit, Lucie had been a calm, happy, carefree child. But from the age of 13 she started to suffer from severe depression, anxiety and panic attacks.

She also began to self-harm, and experienced extreme mood swings. So at 14, she was pulled out of her mainstream school and sent to live in an adolescent mental health unit.

"I had a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), and they mentioned bipolar quite a lot," she recalls.

But none of these seemed to fit the cyclical nature of her symptoms.

Things changed dramatically when she became pregnant at 16 with her son, Toby.

"Within a few months of being pregnant I left the hospital. My symptoms just seemed to disappear. I was happy. I felt really good. I felt mentally really, really well, which was a surprise."

This lasted throughout her pregnancy and her time breastfeeding - but when her periods came back, so did her symptoms.

When Lucie was pregnant her symptoms disappeared and she felt very well

A few years later, Lucie, from Devon, went back to college to study for A levels, but every few weeks she would feel unable to cope with the pressure, and eventually she quit.

Then she embarked on a National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) to become a teaching assistant. This time she struggled through to the final stretch, stopping only two months before the end, when her symptoms became unbearable.

But at 23 Lucie became pregnant again - with her daughter Bella. And again she felt mentally well, despite having to spend months in hospital with severe vomiting.

After Bella was born, however, the symptoms she had been struggling with for years became even worse.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) affects around one in 20 women in the UK.

Some were physical - joint and muscle pain, hypersensitivity to sounds, smell and touch, and extreme fatigue. Others were mental - invasive thoughts, irrational behaviour, forgetfulness, and overwhelming feelings of hopelessness.

"The scariest thing for me was depersonalisation, where I would feel like I was completely disconnected from my body, and like I was in a dream. At points I would find that I didn't recognise the people that were around me. I knew that I should know them, but their faces just didn't make any sense to me," she remembers.

"And at one point, when things were really really bad, I could hear my voice as someone else's, so when I was talking, I couldn't recognise my own voice or my own reflection."

She frequently suffered from suicidal thoughts, which led her to take enormous risks, almost willing her own death.

All these things occurred at monthly intervals, but it wasn't until her husband, Martin, offhandedly mentioned that he should keep quiet before her period, so as not to annoy her, that Lucie began to study the connection between her periods and her symptoms.

"It became pretty clear what was going on," she says. "Within hours of bleeding, I would be fine. I would go from one extreme to the other. I would know that my period was coming and though I suffered from really, really heavy, awful periods, I felt at my best when I was bleeding. I even very carefully planned my wedding day so I would be bleeding because I knew that it was the only time I felt OK."

Up to this point, Lucie had always assumed that her hormones exacerbated the mental health problems she had been diagnosed with. Now she began to wonder if they could be the cause.

Armed with a list of about 30 symptoms and information she had printed off the internet, Lucie went to speak to her GP. At the time, she was consistently being told that she was suffering from post-natal depression after the birth of her daughter, but having suffered from depression in the past, Lucie strongly believed this wasn't the case.

She had been medicated with anti-depressants, anti-anxiety medications and sleeping pills since she was a teenager. And now anti-psychotics were added to the mix.

"Every time I went, they would up something or add something. I was on a very hefty dose of anti-depressants. And I would say to them, 'I'm not depressed… this isn't depression, something else is happening.' I felt like I was losing my mind completely."

Her GP sent her to see a mental health team, who told her that although some of her symptoms were affecting her mental health, she had a physical condition that could not be treated by a psychiatrist. But when Lucie asked her GP if she could see a gynaecologist, he scoffed at the idea and sent her back to the mental health team.

This time they gave Lucie's condition a name: Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) - a severe form of Premenstrual syndrome (PMS). They wrote to the GP recommending that she be seen by a gynaecologist, and "think about medication to prevent ovulation permanently".

This seemed like a possible breakthrough to Lucie, but her GP disagreed with the diagnosis - and insisted that she try every possible alternative treatment before he would refer her.

What is PMDD?

Severe PMS/PMDD affects 5-10% of menstruating women and is often triggered by fluctuations in hormone levels

Some people have a genetic vulnerability to these changes - research has shown that there's often a family history of PMS

While physical symptoms are common, it is the emotional symptoms, e.g. depression, irritability, aggression, which lead to the greatest problems

PMS/PMDD can affect anyone who menstruates, but it most commonly occurs during adolescence, when periods first start, and in over-35s

Hysterectomy is usually a last resort for PMS/PMDD and not undertaken lightly, but it can be an effective cure - patients must receive HRT to ensure that PMS problems are not replaced with menopause problems

She was put on various birth control pills, which made her feel constantly ill, and once the dosage limit was reached for one anti-depressant, another one was added on top.

She was prescribed Mirtazapine, Sertraline, Prozac, Diazepam and sleeping tablets, all of which made her feel numb, and made it harder for her to argue her case.

"It was very difficult. I was at my worst, I couldn't go to the doctors, couldn't even string a sentence together. I couldn't hold a conversation. And then when I was well, I couldn't even remember what I had been like, the weeks prior to that would just be a blur."

It was Lucie's husband, Martin, who ensured that she kept going back to see her doctor, and trying other GPs, in the hope of finding one that would listen to her. Eventually, she met one who recognised that none of her treatments had worked, and at long last referred her to a gynaecologist.

The appointment took place almost a year after her diagnosis of PMDD and she was immediately offered injections, taken every four weeks, which would stop the production of oestrogen in her body, causing her to go into a temporary menopause. If these injections worked, it would confirm her diagnosis of PMDD.

The first two weeks were incredibly difficult, with the worst of Lucie's symptoms flaring up constantly. But after that, as she was bracing for her monthly onslaught to begin, nothing happened, and she felt truly well for the first time in over a decade.

"Suddenly, everything changed… all my symptoms vanished," she says. "I didn't realise how bad I was until they disappeared."

Within two months, miraculously, she was able to come off all the medication that she'd been on since her teens.

Find out more

Lucie spoke to Ouch! the disability podcast - listen here

At her first follow-up appointment, five months after the injections had begun, her PMDD diagnosis was confirmed. And a new, more permanent, idea was raised - a total hysterectomy, the surgical removal of Lucie's uterus and ovaries.

Prior to this, Lucie had been 100% certain that she wanted another child, but she quickly found her conviction wavering.

"It was really important to me but then I knew that would mean coming off this injection, letting my periods come back in, and everything that came with that - and it was just an impossible task," she says.

"I didn't think I would make it if I did that. I thought I'd end up suicidal again, doing ridiculous risky things. It was just a scary feeling."

When Lucie discussed the possibility of a hysterectomy with Martin, he was supportive, but concerned that she might come to regret the decision - which would not only rule out any more children, but make Lucie's temporary menopause permanent. Lucie says she was worried about that too. But then they sat down to write a list of symptoms she had previously suffered from - and this time came up with a total of 42.

"Looking back over that list, there was just no way I could survive that again, knowing what life was supposed to be like, knowing what normal was," she says. "I hadn't known what normal was until now. Martin had seen the change in me and our lives. It was so much better."

As Lucie was coming to terms with the idea of having a hysterectomy, though, she experienced a nasty shock - her symptoms started to reappear.

"The symptoms were just creeping back bit by bit, which was scary, and I started feeling suicidal again. I was so desperate for the injections. I knew that they had helped but suddenly they weren't working, and I was trying to get them earlier and earlier every month. It was really like being addicted," she says.

Lucie's gynaecologist then told her it wasn't possible that the injections were wearing off, and that her diagnosis of PMDD must have been inaccurate. She was told to stop taking the injections and go back to using birth control to help manage her hormones.

"I was thinking that I couldn't do that. I would rather die than go back to what I had been like before," she says.

Help and support

The nurse that had been giving her injections for months recommended yet another GP, and this one agreed to Lucie's request to be referred to a specialist unit that she'd read about, at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in London.

A few months later, Lucie walked into the clinic and told her full story, going back nearly 15 years. When she mentioned that the injections had been wearing off, the doctor replied that this was, in fact, pretty common. That validation was a huge relief.

She was offered an injection taken every 10 weeks instead of four, and for a while it worked so well that it seemed there would be no need for a hysterectomy. But then Lucie started suffering from a new problem brought on by the temporary menopause she had undergone - a loss of bone density that often leads to osteoporosis. She was prescribed Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) to counteract this but it made her extremely unwell.

This made up Lucie's mind and in December 2016, at the age of 28, she had a hysterectomy.

Lucie recovering in hospital after her hysterectomy

Up until the day of her surgery she found herself questioning whether this was the right decision.

But in the year since the operation, despite occasional migraines, she has been able to do more than in the 10 years before it. She has finished her NVQ and is now working as a teaching assistant, doing the very job she never thought she would be well enough to do.

"I still haven't quite got my head around the fact that this is how it is always going to be," she says.

Lucie doesn't feel bitter about the time it took for her to get a diagnosis.

"I got there in the end. I just feel lucky that it was something that could be cured and that I did get to see the best people. I know that when I was younger, the symptoms were all because of PMDD - I have no doubts about that whatsoever - but it just wasn't recognised then like it is now.

"It was just shrugged off as, 'Oh no you know everybody gets PMS. Everybody feels like that sometimes,' and that's not the case."

She does wish, though, that she'd been taken more seriously by her doctors after the birth of her daughter, when her symptoms were at their most severe.

"I wish I'd been listened to more, really. I just wish they'd taken into account what I was saying. If you're feeling like I was feeling, something is quite badly wrong."

The surgery has affected not only Lucie, but all those around her. Martin, a musician, is able to spend more time working, because Lucie can now take responsibility for the children. Toby is old enough to appreciate the positive change in his mother; Lucie hopes that Bella does not remember her the way she was before her treatment for PMDD began. They are now so much happier as a family.

"Is this what everyone else is like all the time? They don't know how lucky they are," Lucie says. "And it's nothing I'll ever ever take for granted."

Follow Natasha Lipman on Twitter @natashalipman , external

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external