The vetting files: How the BBC kept out ‘subversives’

- Published

Broadcasting House in 1959

For decades the BBC denied that job applicants were subject to political vetting by MI5. But in fact vetting began in the early days of the BBC and continued until the 1990s. Paul Reynolds, the first journalist to see all the BBC's vetting files, tells the story of the long relationship between the corporation and the Security Service.

"Policy: keep head down and stonewall all questions." So wrote a senior BBC official in early 1985, not long before the Observer exposed so many details of the work done in Room 105 Broadcasting House that there was no point continuing to hide it.

By that stage, a policy of flatly denying the existence of political vetting - not just stonewalling, but if necessary lying - had been in place for five decades.

As early as 1933 a BBC executive, Col Alan Dawnay, had begun holding meetings to exchange information with the head of MI5, Sir Vernon Kell, at Dawnay's flat in Eaton Terrace, Chelsea. It was an era of political radicalism and both sides deemed the BBC in need of "assistance in regard to communist activities".

Col Alan Dawnay (right) in Cairo in 1918 with T E Lawrence (left) and the archaeologist David George Hogarth

These informal arrangements became formal two years later, with an agreement between the two organisations that all new staff should be vetted except "personnel such as charwomen". The fear was that "evilly disposed" engineers might sabotage the network at a critical time, or that conspirators might discredit the BBC so that "the way could be made clear for a left-wing government".

And so routine vetting began. From the start, the BBC undertook not to reveal the role of the Security Service (MI5), or the fact of vetting itself. On one level this made sense, bearing in mind that the very existence of the Secret Service remained a secret until the 1989 Security Service Act.

Over the years, some BBC executives worried about the "deceptive" statements they had to make - even to an inquisitive MP on one occasion. But when MI5 suggested scaling back the number of jobs subject to vetting, the BBC argued against such a move. Though there were some opponents of vetting within the corporation, they had little influence until the Cold War began to thaw in the 1980s.

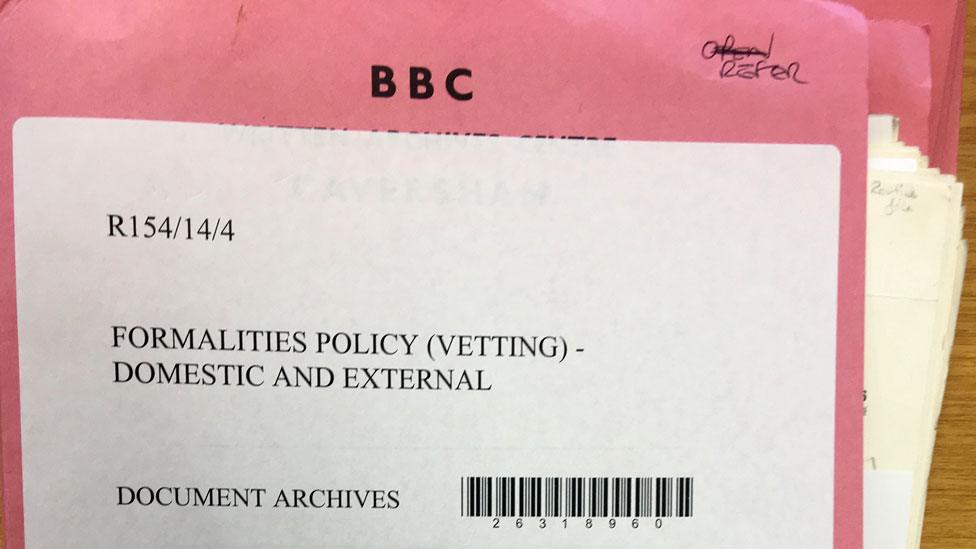

"Formalities" was the code word for the vetting system

This is how the system worked.

Vetting was brought into play once a candidate and one or two alternatives labelled "also suitable" had been selected for a job. The alternatives served a useful purpose. If the first choice was barred by vetting, the appointments board moved easily on to the second. The candidates were told only that "formalities" would be carried out before an appointment was made. This sounded harmless enough; it would allow time to follow up references, perhaps. Candidates did not know that "formalities" meant vetting - and was, in fact, the code word for the whole system.

A memo from 1984 gives a run-down of organisations on the banned list. On the left, there were the Communist Party of Great Britain, the Socialist Workers Party, the Workers Revolutionary Party and the Militant Tendency. By this stage there were also concerns about movements on the right - the National Front and the British National Party.

A banned applicant did not need to be a member of these organisations - association was enough.

BBC Announcers Room in 1938

If MI5 found something against a candidate, it made one of three "assessments" in a kind of league table:

Category "A" stated: "The Security Service advises that the candidate should not be employed in a post offering direct opportunity to influence broadcast material for a subversive purpose."

Category "B" was less restrictive. The Security Service "advised" against employment "unless it is decided that other considerations are overriding".

Category "C" stated that the information against a candidate should not "necessarily debar" them but the BBC "may prefer to make other arrangements" if the post offered "exceptional opportunity" for subversive activity.

The BBC procedure was in principle never to employ someone in Category "A", though a few did get through the net. This contradicted its public position that the BBC controlled all appointments. In theory it did. In practice it gave that choice to MI5 in Category "A" cases.

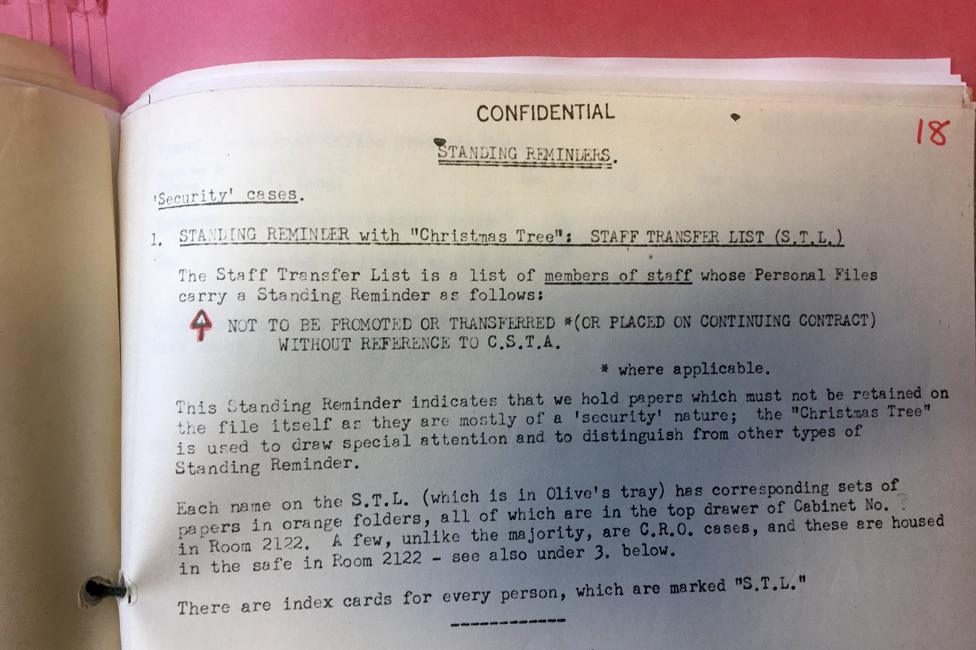

If staff came under suspicion only after they had been employed by the BBC or applied for transfer to a job that needed vetting, an image resembling a Christmas tree was drawn on their personal file.

The "Christmas Tree" also resembles an upward-facing arrow

This "tree" was an important part of the process. The BBC maintained a "Staff Transfer List" which named staff who needed to be checked if they were to be promoted. A tree added to the file alerted the administration that this was a security case. Also written on to their file was a so-called "Standing Reminder". This stated: "Not to be promoted or transferred (or placed on continuous contract) without reference to [Director of Personnel]."

So keen was the BBC to maintain secrecy that it secretly removed the Standing Reminder from someone's file if they went to an Industrial Tribunal, which had the power to call for personal files. It was also agreed to (misleadingly) explain away a stamp on a file saying "Normal Appointments Formalities Completed" by pretending that it referred to "routine procedures, Next of Kin, Pension etc".

The Christmas tree was eventually dropped in 1984 because it was said to attract too much attention. It attracted a great deal of attention when the Observer described it in 1985. The day after publication, someone hung some Christmas decorations on the door handle of Room 105 in Broadcasting House, from where the system was run.

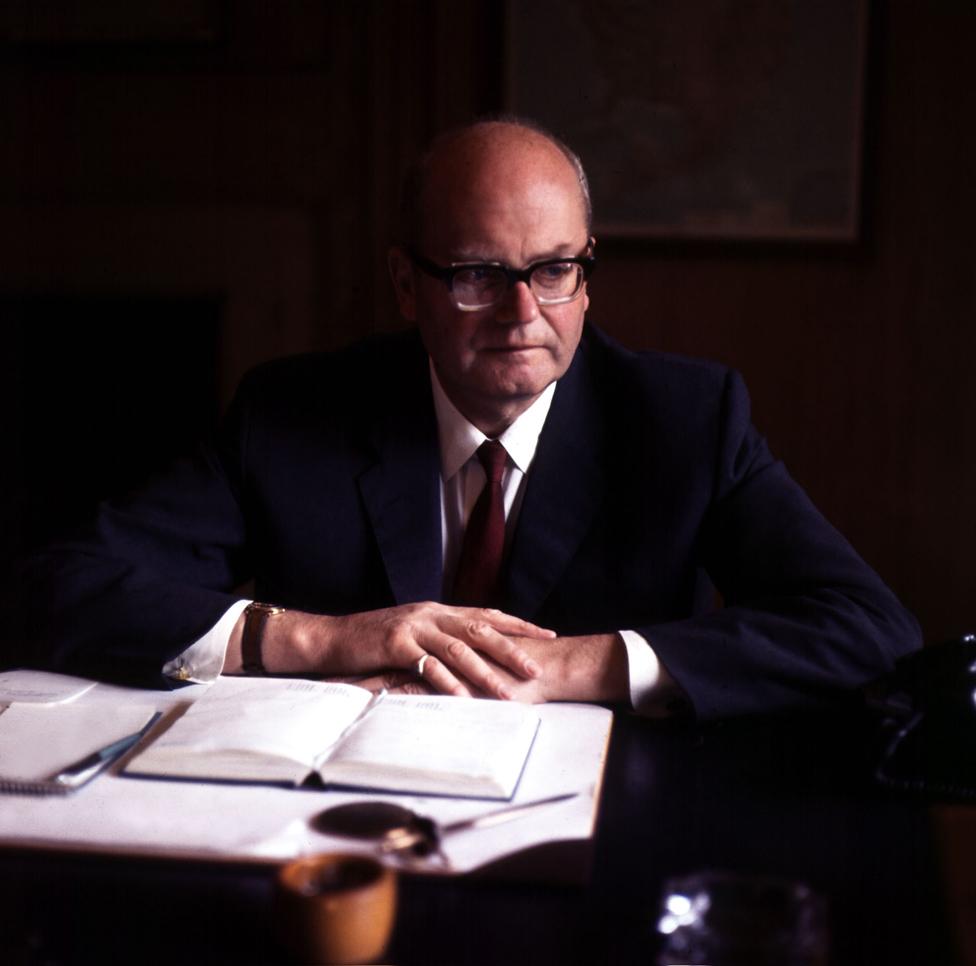

An interview given in 1968 by BBC director general Sir Hugh Greene shows the BBC's policy of denial and obfuscation in action.

To a reporter from The Sunday Times in February Greene blithely and misleadingly declared: "We have a staff of 23,000 and in that community we have people of all descriptions, including what you call pansies" - the word had apparently been used by the reporter - "and also communists. But that's none of my business. We don't conduct an inquisition on people who join the BBC."

Hugh Greene in 1968

It was true that neither the BBC nor MI5 used homosexuality as a reason to block someone, but stopping the employment of communists was very much part of Greene's business and, if not the BBC itself, then the Security Service did conduct inquisitions.

The files reveal that BBC tactics for handling this interview had been drawn up by MI5 itself - known delicately as the "College" in BBC memos. In advance of the interview, and in a rare departure from prevailing policy, a BBC official had suggested to "College" that "the need for vetting no longer existed, in peacetime". The BBC indicated that it was willing to admit publicly that staff involved in plans for broadcasting in time of war - called "emergency defence work" - and any aliens employed were checked. However, a BBC memo records: "College do not favour reference to vetting in any way whatever."

To underline the point, an MI5 official telephoned to say that "no direct admission of vetting should be made". If pressed, the BBC could admit that "something of this sort" was carried out "in relation to War Planning purposes" and "where aliens were concerned".

Nevertheless, the Security Service "would prefer that as little reference should be made to this subject as possible".

The satirical show That Was The Week That Was helped cement Hugh Greene's reputation as a liberaliser

MI5 suggested that questions could be diverted from Greene to someone on the "personnel side of things". And "perhaps stress could be laid on a stiff recruitment procedure and the fact that references are taken up very thoroughly". This last phrase was taken up by the BBC very thoroughly itself, and it appears in many of the BBC responses over the following years. Cleverly ambiguous, it implies that the references taken up were those given by an applicant. In reality, the references were supplied by the Security Service.

Greene followed the MI5 line. He told the Sunday Times that he would not answer any questions about vetting but would leave that to a senior subordinate. The paper seems to have gone along with this. There is no questioning of Greene on this matter in the published interview in the Sunday Times.

However, Greene's nominated spokesman, the director of administration, John Arkell, did not quite follow the script with which he had been provided. At first he repeated the denial: "We don't ask about religion or politics." However he then wobbled. "If someone is a communist it's of no relevance, unless, of course, he is working in a particularly sensitive area." The Sunday Times reporter then asked Arkell whether he had confidence in British security vetting and Arkell wobbled again: "In this imperfect world perhaps sometimes someone suffers," he replied, and the implication was clear, though the paper did not pursue the point.

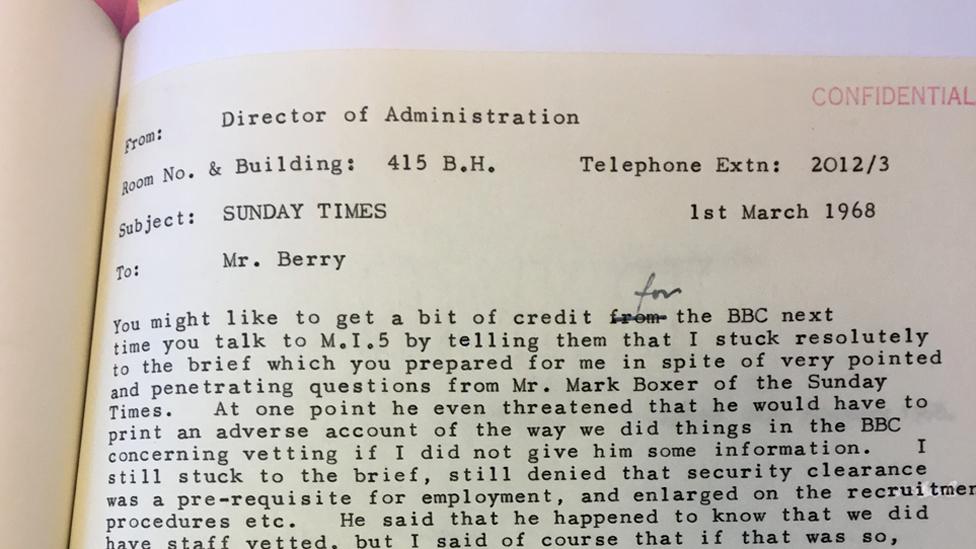

John Arkell on a visit to BBC Wales in 1970

Arkell then hurriedly repeated the standard denial: "I must point out that security vetting isn't a prerequisite for getting a job at the BBC."

In fact for about 6,000 BBC jobs at the time, it was. Arkell's comments led to some raised eyebrows. One BBC official accused him of making "an open avowal" of vetting. However, Arkell himself was pleased with his performance and encouraged a BBC colleague to use it "to get a bit of credit for the BBC with MI5".

When this resulted in a letter from the Security Service congratulating Arkell for "standing up so creditably to the questioning" the critical BBC official fell into line, commenting merely that Arkell's denial had to be maintained "unvarnished, unglossed and unexpanded".

Greene's refusal to answer questions was no surprise to insiders. Although he had been a liberalising influence in the BBC since becoming director general in 1960, he was firmly in favour of vetting. Not long after taking over, he had led a BBC delegation in talks with the Home Office, which was asking why so many BBC applicants had to be vetted. MI5 was worried that it was open to being sued by individuals, since its directive required it to concentrate only on "countering threats of subversion and sabotage". It wanted to vet only the applicants for a limited number of jobs.

Arkell suggests that the BBC can get credit from MI5 for his performance under "penetrating" questioning from the Sunday Times

But Greene resisted any change. The BBC actually argued for more vetting, to prevent infiltration by "subversives", but felt that it could publicly admit to checking some key staff. MI5 wanted to lessen the burden placed on it by vetting - but insisted on almost total secrecy.

It took some time for the argument to be resolved. The Security Service managed to square its activities with its directive and the BBC removed 528 staff from the vetting system. Among these were 81 staff in the Make-up and Wardrobe Department, 20 in the Gramophone Department and 21 in the Library. Sixteen staff in Religious Broadcasting were also excluded, though the BBC could still request vetting for any individual there.

Thus were such staff no longer regarded as dangers to the state.

Banned applicants did not know why they had been turned down, though they might have guessed.

One notorious case involved the journalist and broadcaster, Isabel Hilton (who later received an OBE for her reporting). She was refused a job in BBC Scotland in 1976 because, she believes, she was guilty by association with a member of the Communist Party at Edinburgh University - a fellow member of the university's China-Scotland organisation.

Isabel Hilton

After unprecedented protests from the BBC executive who wanted to employ her, Alastair Hetherington, she was eventually offered the job. But it was too late, she had gone elsewhere. She was later told apologetically by Michael Hodder, the last BBC official who acted as liaison with the Security Service, that it had all been a "mistake", but the episode still angers her.

"I still feel indignant. It's the lack of accountability that bothers me and the fact that nobody in the BBC ever apologised, explained - or made any public statement in my defence or to acknowledge their error," she says.

"They went into an institutional defensive huddle without regard for what their actions might have done to me, my reputation, my career etc - nobody in the BBC took responsibility or seemed to feel that they should make any move to repair any damage. I felt it was a squalid way to behave and I still do.

"More seriously, beyond the particulars of my own case, I felt that the BBC had betrayed public trust by promoting a system in the UK by which the secret police were licensing and blacklisting journalists. Whenever I hear the BBC boasting about its fine traditions of journalism, I feel a minor stab of outrage."

Hilton did eventually work for the BBC, presenting the World Tonight on Radio 4 in the 1990s, and later the Radio 3 arts programme, Night Waves.

Another candidate who was rejected on MI5's advice was Tom Archer, who worked as a BBC freelancer in Bristol in the 1970s, but was turned down when he applied for staff jobs from 1979 onwards. Archer says he had been "an active socialist at university", but this was something the BBC usually ignored as youthful enthusiasm. There had to be another reason, and an editor in Bristol who wanted to employ him, Robin Hicks, discovered it: Archer was being blocked because a close relative had allegedly joined the Socialist Workers Party. Hicks protested but to no avail.

Tom Archer in 1983, when he was still able to get work at the BBC as a freelancer

Archer's career flourished outside the BBC, however - at Channel 4 and Granada - and he eventually worked his way back. In 2008, he became controller of BBC factual programmes - based in Bristol.

"I was angry and even frightened at the time," he says, casting his mind back to 1979.

"I feared that everything would be blocked off for me. We were a young married couple. I sent back the video recorder and sold the car. They did it in a secret cack-handed way.

"It was of course a complete triumph when I went back."

At the same time Tom Archer's job applications were being rebuffed, a senior BBC appointments official was arguing that it was time for vetting to end. In December 1979, Hugh Pierce pointed out that over a recent two-year period only 22 people had been excluded out of thousands vetted. He said, therefore, that "the process of vetting could be reduced". He doubted if the 22 could have done much damage, as "any personal bias... could have been spotted and checked." He recommended continued vetting for those with access to official secrets and in the BBC World Service, where many foreign staff were employed. Beyond that, he said, "We should abandon forthwith the current requirement to vet wholesale categories of applicants. We should replace a rather crushing machinery by a more flexible service."

The last line of his 10-page report was prophetic. He warned that if the scale of vetting became publicly known, it "would be grounds for ridicule and vilification". His recommendation was not followed and his prophecy came to pass when the Observer story was published in August 1985.

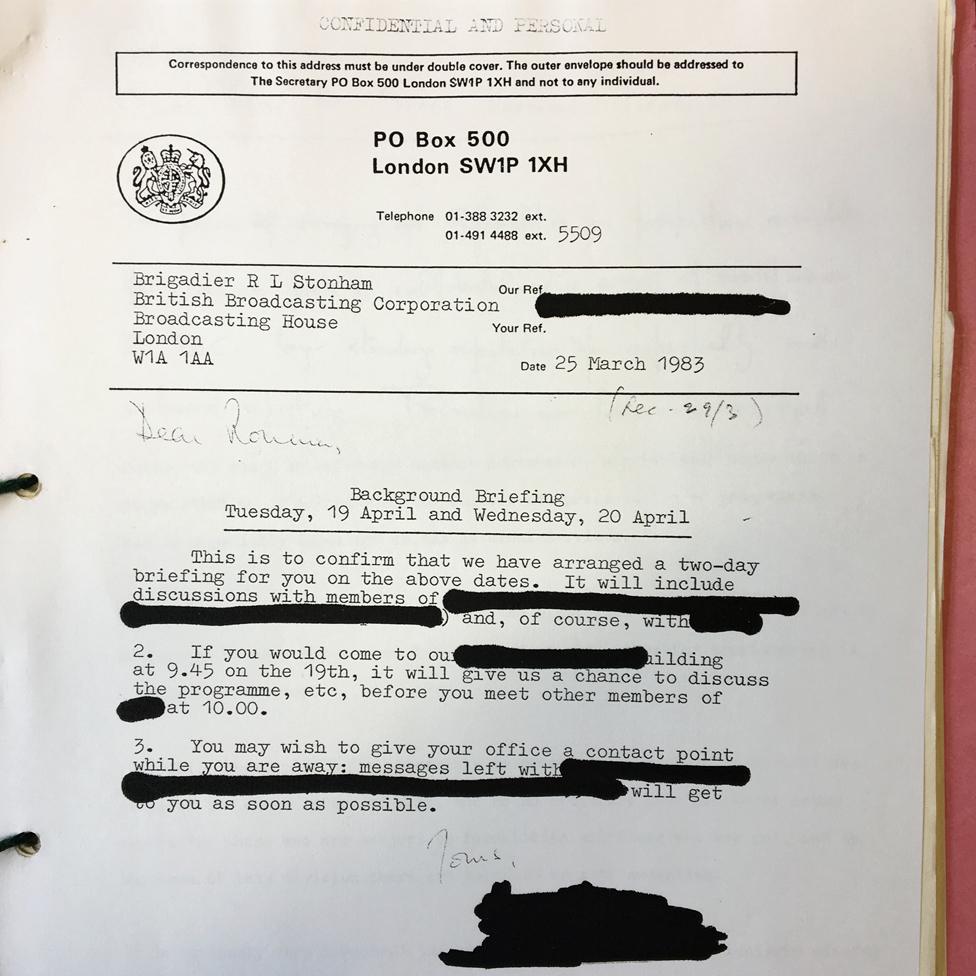

The BBC files on vetting have themselves been vetted to remove the names of MI5 staff

Despite the rejection of Pierce's proposal to reduce vetting significantly, steps were taken before long to further cut the number of staff subject to it. Since the start of the policy, journalists had always been included in the system, but a review in 1983 resulted in about 2,000 posts being removed from the list - including some junior editorial jobs - bringing the total number down to 3,705.

The man who conducted this review, the BBC official in charge of liaison with MI5, was Brig Ronnie Stonham, a former Royal Signals officer, who also produced an updated "defensive brief". The first line of this was the usual blanket denial: "It can be stated categorically that BBC staff are not subject to a security clearance as a prerequisite for employment." It is hard to reconcile this with reality, as Stonham himself says in his report that in 1982 1,287 names were sent to MI5 for "counter-subversion" clearance.

At the top of the BBC support for vetting was clearly waning, however. The vice-chairman of the Board of Governors, Sir William Rees-Mogg, had already questioned it before the Observer broke the story that broke the system.

"It operates, unknown to almost all BBC staff, from Room 105 in an out-of-the way corridor on the first floor of Broadcasting House - a part of that labyrinth on which George Orwell modelled his Ministry of Truth in Nineteen Eighty-Four," wrote reporters David Leigh and Paul Lashmar.

"The legend on the door - 'Special Duties-Management' - gives little away," the story went on. "Behind that door sits Brigadier Ronnie Stonham."

The headline - Revealed: How the BBC vets its staff.

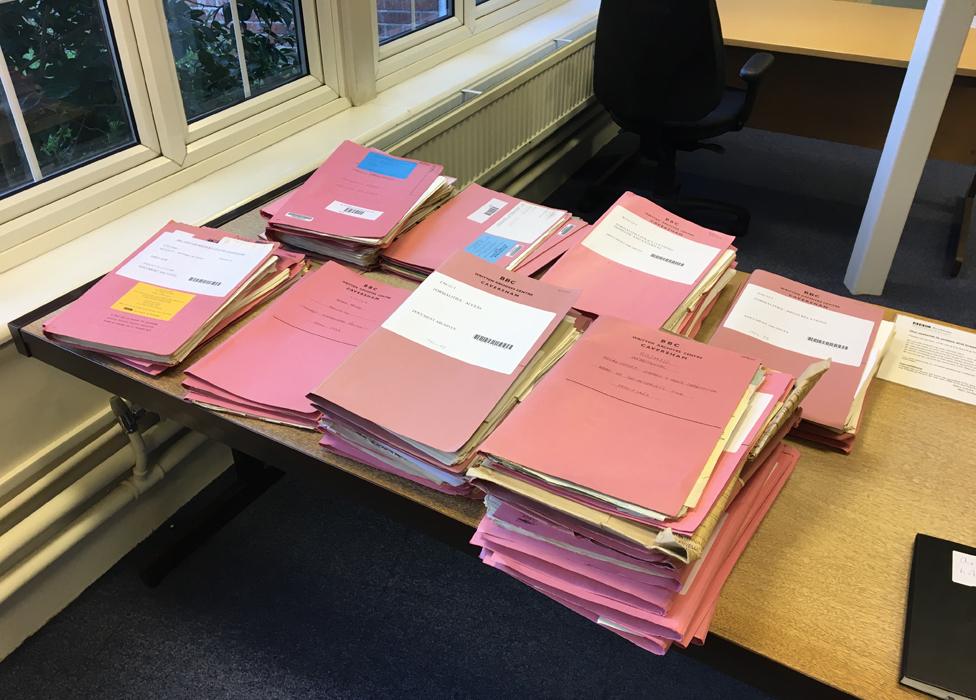

The vetting files at the BBC's Written Archives in Caversham

This time, there were facts and case histories which made the standard denials useless.

Stonham's boss, director of personnel Christopher Martin, had initially tried the standard denial routine with Leigh and Lashmar, but then got the Home Office to agree a new line - a public acknowledgment that vetting had taken place, but was now being reduced.

There were some who marvelled that the BBC had managed to keep the secret for so long - it is evident from the anxiety expressed in the files that the corporation would have been hard pressed to hold its line if it had been pushed really hard by the press. "This story is 50 years old and it has taken the press that long to find it," said the BBC director general at the time, Alasdair Milne.

The Observer's revelations brought about a major change.

Almost immediately, Ronnie Stonham recommended confining counter-subversion vetting to senior editorial staff but BBC management went further. In October 1985 the BBC announced publicly that vetting would in future be applied only to a few operational people at the very top, to those who would run emergency broadcasting (which meant the then secret wartime broadcasting system in the event of nuclear war) and to those staff in the BBC World Service who were thought to be vulnerable to hostile infiltration. All vetting of staff not in those categories would cease.

BBC correspondents, such as Paul Reynolds, remained subject to vetting even after 1985

But behind the scenes there was still resistance from some quarters. A rearguard action was fought to keep specialist domestic and foreign correspondents on the vetting list, on the grounds that "the BBC's credibility depended on their integrity". A dodge had to be devised, and so correspondents were quickly reassigned to a list of those who had access to restricted government information - an access they in fact did not have.

The upshot was that vetted staff were reduced to 1,400 in the domestic services and 793 in the World Service. The system was further refined in 1990, following the Security Service Act, under which all vetting in the BBC stopped except for those who would be involved in wartime broadcasting and those with access to secret government information.

Then, two years later, the wartime broadcasting system was stood down, so vetting was further cut back. The BBC will not say whether any staff are vetted these days. "We do not comment on security issues," a spokesperson said. But any residual vetting, of people needing access to classified information for emergency planning for example, would be open and known to the person. There is no more secrecy as once there was.

By the time the wartime broadcasting system was wound up, Stonham had retired, and his role as MI5 liaison had been taken by a personnel officer from the news division, Michael Hodder, a former Royal Marine. Hodder oversaw the residual vetting and dealt with a few cases informally in the World Service.

There was an employee in the Burmese Section who was giving the names of dissidents to the Burmese Embassy in London. Another was the case of a Saudi employee who turned out to be on the payroll of both the BBC and the Saudi embassy. A third involved an applicant for a job in the Arabic Service, who was related to a notorious terrorist.

It was Hodder who saved the files for history.

He ignored an instruction to destroy them and crated them up in a safe for delivery to the BBC Written Archives Centre. He did shred all Security Service material on staff that the BBC held. However, he ensured that one personal file was kept - that of Guy Burgess, who worked for the BBC during the war.

The BBC even put his file online in 2014 but of course in this case the vetting had failed - and there was nothing in the file of Guy Burgess to indicate that he was in in fact a Soviet spy.

Paul Reynolds was a BBC correspondent from 1978 to 2011.