Community volunteers with speed guns strike back at motorists

- Published

John, a volunteer, clocks a motorist with his laser gun

A growing movement in the UK is shifting the power of catching speeding motorists from the police, to the people.

"My daughter was going to school and one of her friends was killed by a vehicle," says John Ryan.

"The school assembly that morning when the children were told was terrible. The school didn't recover for about a year. It had a very big impact on the children and particularly my daughter."

Now, 20 years later, the retired bus driver has joined a network of volunteers trying to make the roads safer.

Twice a week, he patrols the area where he lives in west London with a speed gun and two police community officers, noting down car registration details of drivers breaking the limit.

In London's scheme, police community support officers record registration details

In one spot next to a school, he typically catches 20 vehicles breaking the 20mph limit in a one-hour session. He once caught a car travelling at 45mph.

"It just shows what we're up against as a community," he says.

Fatal problem

Every year, about 1.25 million people die in road accidents around the world, and on average, five people are killed on Britain's roads each day. Speed is a contributing factor in around half of fatal road collisions, according to the Metropolitan Police. And the faster a vehicle travels, the worse injuries will be.

Current deterrents for motorists are flawed. Speed cameras create resentment and only work in specific locations. Police with speed guns are effective, but this approach can be a drain on their time.

So passing the baton of the speed gun to John and fellow volunteers could be a solution.

Thousands of people like John are volunteering around the country, in a patchwork of groups.

Hear more

World Hacks reporter Dougal Shaw with Inspector Philip Spaul who co-ordinates volunteers

You can learn more about volunteer speed monitoring groups in the latest People Fixing the World podcast from the BBC World Service, including a confession from reporter Dougal Shaw

The group John volunteers with is Community Roadwatch, which Transport for London (TfL) runs with The Metropolitan Police.

"It's getting the community involved in reclaiming their streets," explains Siwan Hayward, head of Transport Policing at TfL.

"We're confident it's having a massive impact, without putting drivers through fines or the courts."

No fine, no points

There is a crucial difference when volunteers, like John, rather than the police, wield speed guns.

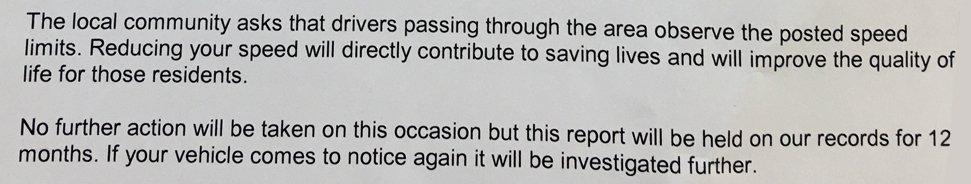

Motorists who are caught simply receive a warning letter from the police telling them that neighbourhood volunteers have recorded them speeding.

The letter contains an educational message and an appeal to their conscience - but no other penalty, no points or fine.

Aylmer Road in north London has been used as a test bed for Community Roadwatch

However, if they receive three of these letters, they may get a home visit from a police officer and their vehicle details could be put on a police database.

Of the 35,000 letters it has sent out to motorists in London in the past two years, TfL says only 2% of recipients have re-offended.

A study it conducted in Aylmer Road, in Barnet, north London, suggested that volunteers working for a year were able to bring down the average speed by 11mph, to 31mph - below the 40mph limit.

'Evil eye'

But can a stiff letter telling you off really have impact?

Daniel, a Londoner, says it can. "I've got a young family and if I see someone driving recklessly I'm the first one to give them an evil eye.

Extract from a typical letter a motorist could receive when caught speeding by volunteers

"For the community to be looking at me that way, yeah it had a big impact."

The fact that there was no fine or penalty, he says, removed any anger or frustration. This allowed him to focus on the fact he was in the wrong.

He was moved to write back to the police thanking them for the letter.

Starting Gun

One of the first forces to start working with volunteers was Cheshire Police in the mid-2000s. It was inspired by a community in Somerset, recalls Brian Rogers, head of Roads Policing in Cheshire at the time.

A laser speed gun can cost around £3,000

Locals had spontaneously bought a speed gun and began sending registration details to the police.

Cheshire Police decided to harness that people power, but also to organise it and provide training and support.

It's a good idea, says Brian, because police resources can't meet the level of complaints when it comes to speeding.

He's not convinced volunteers have a significant, lasting impact on reducing road accidents but he thinks the scheme can empower communities, in keeping with an important British principle, policing by consent.

Vigilantes?

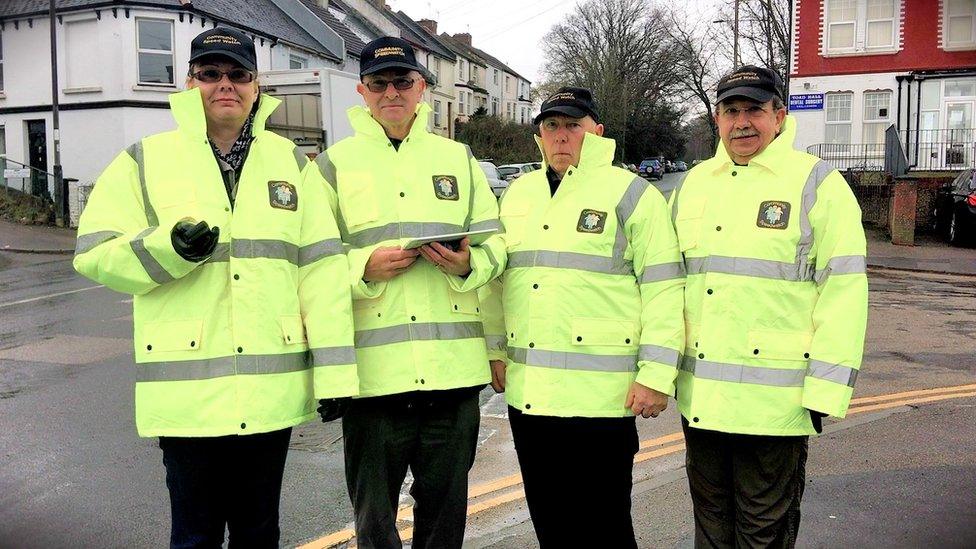

Not all motorists consent to being judged by fellow citizens, though. Irate motorists are an occupational hazard, especially for the thousands of volunteers who operate across the UK without any police support on hand.

And volunteers have an image problem too, according to Jan Jung in Hastings, who runs an umbrella group called Speedwatch, external.

"The perception is that these people are vigilantes, they're hobby policemen, or they just have nothing better to do," he explains.

Volunteers say they learn to take the abuse from motorists in their stride

He advises volunteers to manage their emotions in a confrontation and keep things impersonal. If you recognise a neighbour, he warns, you should avoid eye contact.

Through his Speedwatch group, his ambition is to make volunteers a force to be reckoned with. At the moment the work of volunteers across the country is too uncoordinated to be as effective as it could be, he says.

If you offend in Newcastle then Doncaster, for example, the current localised system isn't intelligent enough to escalate the stern letters.

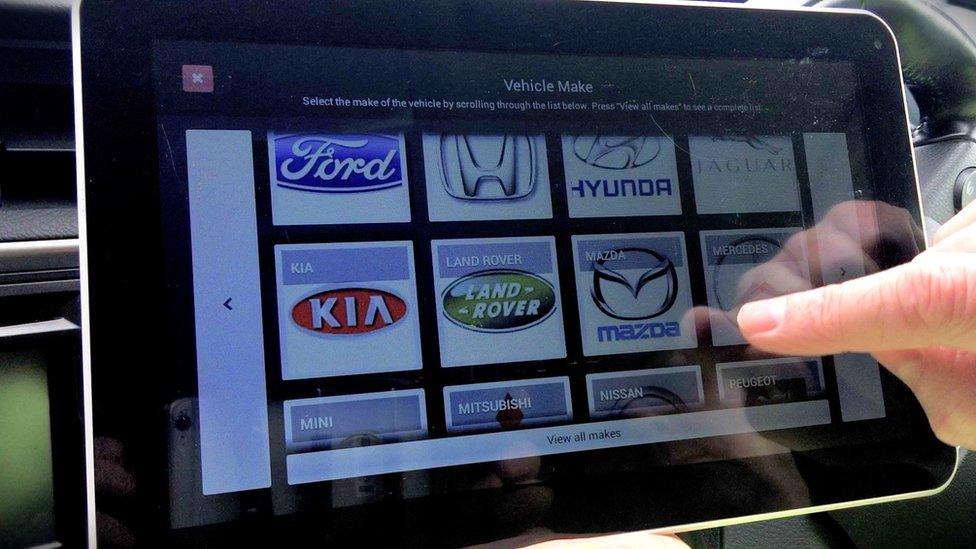

Speedwatch created a system to enter details of speeding cars at the roadside

For this reason, Speedwatch has developed a computerised, super-database that it wants other groups to join.

Currently it only includes Sussex and Kent, connecting 315 volunteer groups.

But the organisation hopes to connect the several thousand groups that are currently operational around the UK.

"If this becomes a national system it can seriously impact speeding," says Jan. "There's no doubt about it, it will."

Follow Dougal Shaw on Twitter @dougalshawbbc, external

You can learn more about volunteer speed monitoring groups in the latest People Fixing the World podcast from the BBC World Service

Read more from World Hacks

More than £14bn is spent on chewing gum around the world each year, but a lot of that gum will end up stuck to the ground. British designer Anna Bullus is on a mission to recycle it into useful objects, cleaning up our streets in the process.