'I jailed the man who raped me as a child'

- Published

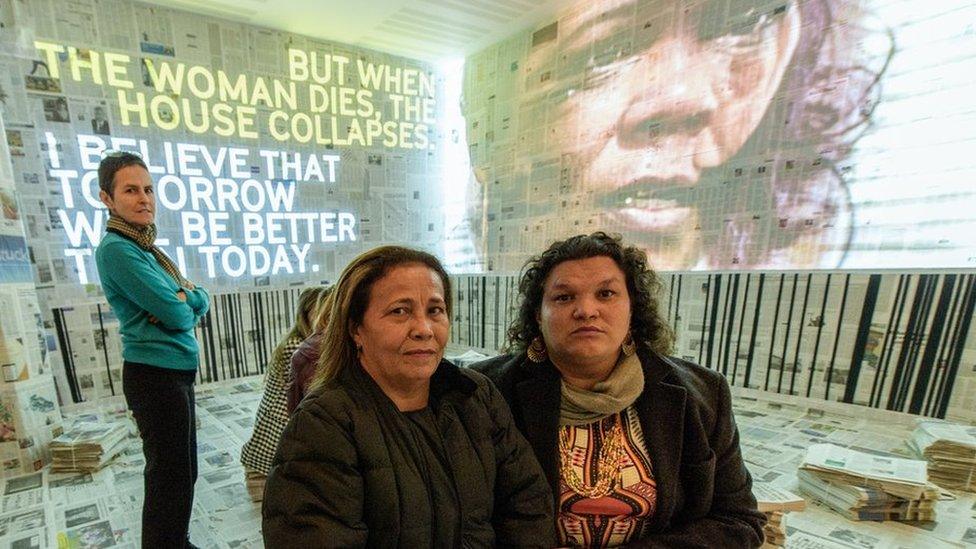

Tabata and Fabricio met again after 12 years, in December 2016.

Tabata had been only nine years old when he came into her life. He was a 39-year-old married man and family friend who abused and raped her for more than two years.

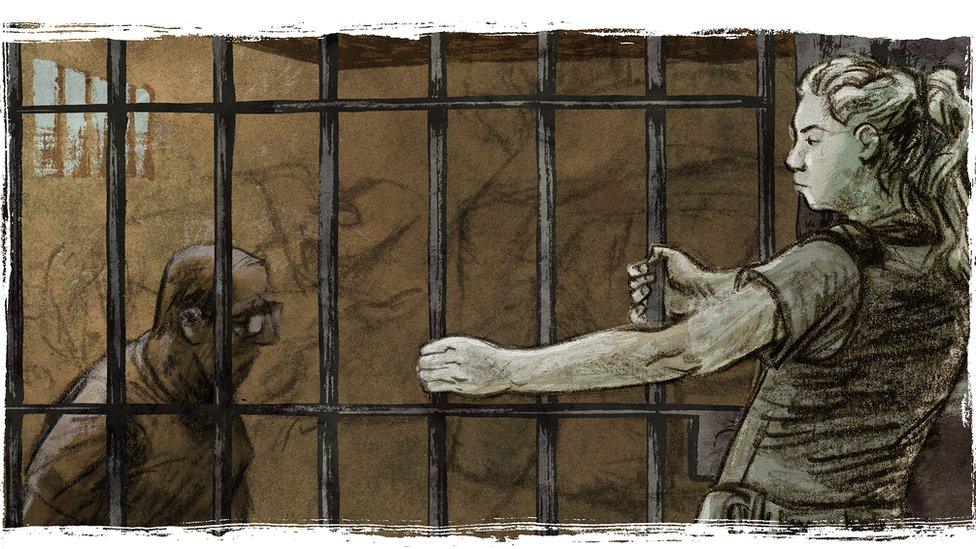

But this time he was handcuffed. It was Tabata who gripped his arm tightly, not him gripping hers. And in her other hand she held a gun.

She took him to his cell, locked it, and left with a sense of relief, she says, as though she had "closed a circle".

Fabricio was a photographer keen on nature, very friendly and a good talker. He charmed those around him with stories about his travels - about beaches, rivers and other faraway places.

Shortly after meeting the family, he became friends with Tabata's dad. Both men played football together in the evenings, and soon Fabricio and his wife started joining Tabata and her parents on trips- camping and trekking in the countryside near where they lived, on the banks of the Uruguay river in southern Brazil.

"It didn't take long for him to start molesting me," Tabata says.

"He would come close and start groping me. I didn't understand what was going on. It bothered me, but I was too young to understand it was a crime."

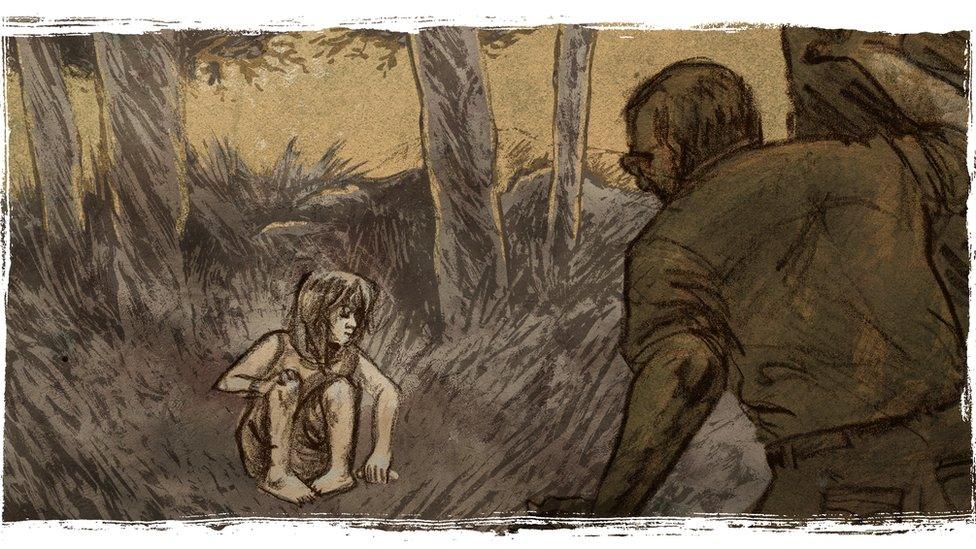

When they found themselves isolated in a maze of trees, or when they were bathing in the river out of sight of the others, he would rape her, Tabata says.

"One day I was sent with him to fetch water for the camp," she remembers.

"He started groping me but I managed to escape and run ahead of him.

"My parents didn't even ask why I had arrived first. It wouldn't have even crossed their minds that he could abuse me, because they trusted him so much."

Tabata says many times she felt like telling the truth to their parents but held back.

"My dad had always been very volatile and prone to flashes of anger. I was scared that he might go and kill the photographer and go to prison. A thousand thoughts cross the mind of a child. But I also feared my parents wouldn't believe my story," she says.

The abuse would last two-and-a-half years.

As time passed, the man began to take advantage of his knowledge of the family routine.

He knew Tabata had an older sister who was studying to become a teacher, that her mum worked in the evenings and that her dad would be playing football. That's when he'd show up at their house.

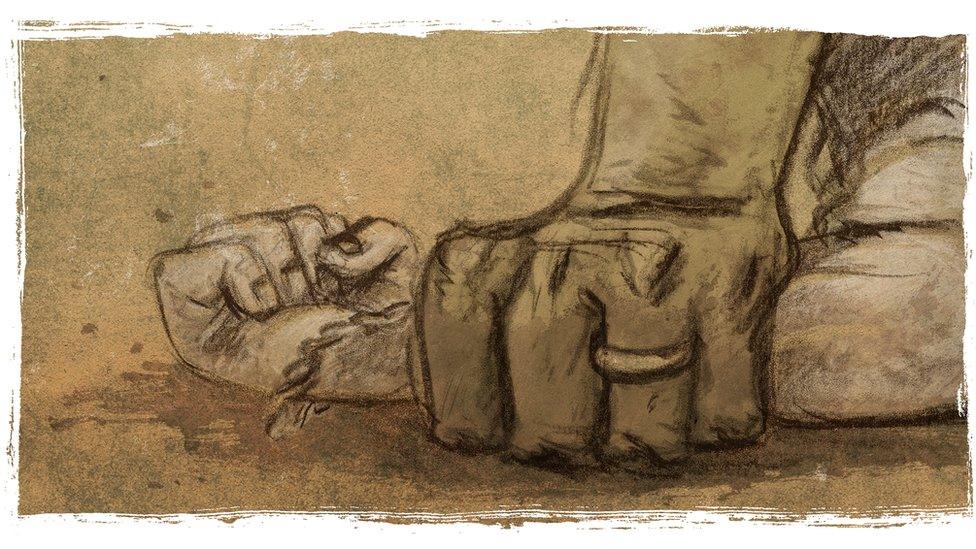

"He'd say: 'Just a little bit, just a little bit.' He never slapped me but held me very tight and forced me to comply," Tabata says.

By the time she was 11 she had begun reacting strongly, shouting, cursing and trying to resist.

She was going to tell her mother, but gave up on that idea when her mother's health deteriorated, to avoid adding to her problems.

Around the same time, her dad was caught having an affair with Fabricio's wife and the old friends became foes. So, to Tabata's great relief, her tormentor suddenly disappeared.

Over the next few years, she tried to forget the details of the rapes, but she couldn't. She was haunted by the memories.

She began sharing her secret with some of her school friends to vent her emotions.

When she was 16, one of her friends finally broke the news to Tabata's horrified mum. But it turned out that her parents had already discovered Fabricio was a paedophile.

"She told me that the photographer had abused other girls. That made me feel so angry," Tabata says.

"I thought I had been the only victim, but then I realised he was also ruining other girls' lives."

Seven years after the first abuse, she reported the crimes to the police but no investigation was launched. Six years after that, when Tabata had already finished a law degree and was training to become a police officer, it was still pending in the prosecutor's office.

"I went personally to ask why the case wasn't moving on. [The prosecutor] was very rude to me. He said it had been a long time ago, there was no evidence and I had taken too long to come forward," Tabata says.

Tabata had lost all hope of seeing Fabricio behind bars, when her father had the idea of finding out whether other young girls had complained to the police.

So Tabata went to speak to the family of another of his victims.

This evidence was crucial to reopening the case.

Fabricio was sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in jail - but only served one year

Fabricio claimed Tabata had made up the story to help her father take revenge after their falling-out, but he was sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison. Even then he remained free, however, pending an appeal.

Tabata was now 24 and finishing her training in the police academy. She says her childhood abuse shaped her choice of career.

But despite her instinct to try to "catch all rapists", she kept her distance from rape cases during her daily routine at work, once she had graduated from the academy.

"I wouldn't be able to control myself and be professional in extreme cases, such as a baby being raped," she says. "And my role as a police officer is to carry out my duties in accordance with the law."

However, a special call of duty came one day in December 2016, when Fabricio lost his appeal.

He'd been hiding in a remote riverside ranch.

"It was my colleague who actually arrested him, but I made a point of locking him up behind the bars," Tabata says.

Reporting the crime and eventually seeing Fabricio jailed was a "healing process", she says.

If you have been affected by child sexual abuse, sexual abuse or violence, help and support is available here.

After the abuse, Tabata says she felt ashamed of her body and regarded sex as something bad.

She says she has to work hard to trust people and develop relationships.

Her story can be seen as a warning for families, she says.

"I would tell parents to talk a lot with their children and prompt them to talk about any improper adult behaviour. And to say they will believe their stories," says Tabata.

"I always say that the victims are never to blame. What happens is not because of their behaviour or the clothes they wear but because the aggressor is a sick person."

In the end, Fabricio was given early parole, serving less than a year of his seven-and-a-half-year sentence.

Tabata's name has been changed to protect her identity. At her request, the BBC has also changed Fabricio's name and has not mentioned the city in which the abuse took place.

Click here to read the story in Portuguese

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.

- Published13 September 2017

- Published14 January 2018