'I was kidnapped in London and trafficked for sex'

- Published

Anna came to London from Romania intending to study, but first she needed to earn some money. She took temporary jobs - waitressing, cleaning, maths tutoring. Then one day in March 2011 she was snatched off the street, flown to Ireland and put through nine months of hell.

Anna was nearly home. There was just enough time to nip inside and eat lunch before leaving for her next cleaning job. She was wearing headphones and listening to Beyoncé singing I Was Here as she walked down the street in Wood Green, north London. She was just a few doors away.

She reached into her bag to pull out her keys when suddenly someone grabbed her by the neck from behind, covered her mouth, and dragged into the back of a dark red car.

There were three of them, two men and a woman. They were slapping her, punching her, and screaming threats in Romanian. Her ears were ringing. The woman in the passenger seat grabbed her bag and pulled the glasses from her face. If she didn't do what they told her, they shouted, her family in Romania would be killed.

"I didn't know what was happening or where they were taking me," Anna says. "I was imagining everything - from organ harvesting or prostitution, to being killed, to God knows what."

The woman was going through her bag, looking in her wallet, scrolling through the recent calls and Facebook friends on her phone, looking at her papers. Her passport was there - she carried it everywhere after her previous one was stolen from her room.

Anna could see there was no point trying to escape from the car, but when they arrived at an airport and she was left alone with just one of the men, she began to wonder if this was her chance. Could she appeal to airport staff for help?

"It's hard to scream when you feel so threatened," she says.

"They had my papers, they knew where my mum was, they knew everything about me."

It was a risk she couldn't bring herself to take.

Watch Doing Money, a drama based on Anna's story, at 21:00 on BBC Two, on Monday 5 November

Viewers in the UK can catch up later online

At the check-in desk, she was crying and her face was red, but the woman behind the counter didn't seem to notice. When the man presented their passports, she just smiled and handed them boarding cards.

Trying to pretend they were a couple, he rushed Anna through security to the boarding gates, and took seats right at the back of the plane. He told her not to move, not to scream and not to cry, or he would kill her.

Anna heard the captain announce that they were flying to an airport in Ireland - she'd never heard of it. Her face was wet with tears as she walked off the plane, but like the woman at the check-in desk the air stewardess simply smiled.

This time Anna had decided that once in the airport she would run, but it turned out to be no bigger than a bus station and two more Romanian men were waiting for them.

The fat one reached out for her hand, smiled and said, "At least this one looks better." It was then that she realised why she had been kidnapped.

"I knew, at that point, that I was going to be sold," she says.

'Anna' spoke about being held captive by sex traffickers on the BBC's Outlook programme

The men drove her to a dirty flat, upstairs, not far from a bookies. The car broke down on the way.

Inside, the blinds were closed and the air smelled of alcohol, cigarettes and sweat.

Men smoked and looked at laptops in the living room. On the table more than a dozen mobile phones rang, buzzed and vibrated constantly, while girls wearing little or nothing came and went between rooms.

Anna's clothes were ripped from her body by a woman wearing a red robe and flip flops, assisted by some of the men. And from then on she was brutalised.

Pictures were taken of her in underwear in front of a red satin sheet pinned to the wall, so that she could be advertised on the internet. She was given more names than she can remember - she was Natalia, Lara, Rachel, Ruby. She was 18, 19, and 20, from Latvia, Poland, or Hungary.

She was then forced to have sex with thousands of men. She didn't see daylight for months. She was only allowed to sleep when there were no clients but they came round the clock - up to 20 of them per day. Some days there was no food, other days maybe a slice of bread or someone's leftovers.

Deprived of food and sleep, and constantly abused, she lost weight fast and her brain stopped working properly.

Customers paid 80-100 euros for half an hour, or 160-200 euros for an hour. Some left Anna bleeding, or unable to stand, or in so much pain that she thought she must be close to death.

Others would ask her if she knew where she was, if she'd been out to hear the traditional music in the pubs, if she'd visited the local beauty spots.

But she says they knew that she and the other girls were held against their will.

"They knew that we were kept there," she says. "They knew, but they didn't care."

It was obvious from the bruises which covered every inch of Anna's body - fresh ones appearing every day where older ones were beginning to fade away - and it didn't bother them.

She hated them all.

Find out more

Anna spoke to Jo Fidgen on Outlook on the BBC World Service

You can listen again here

In July, four months into Anna's captivity, the races were on and the phones were ringing more than ever. Then one day the police crashed into the flat and arrested all the girls. Mysteriously, the men and the woman who ran the show, had disappeared in advance with the laptops and most of the cash. Anna wondered how they had known the police were coming.

The police took pictures of the flat, of the used condoms and the underwear and told Anna and the other three trafficked women to get dressed. She told them that they didn't have any clothes and that they were being held there against their will.

"You could clearly see there were signs that we had no power over anything - no clothes, no identity papers," she says. "I tried to tell them, nobody listened."

She was glad to be arrested, though. She felt sure the police would eventually realise that they were victims. But still they didn't listen.

The four women spent the night in a cell and were taken to court the following morning. A solicitor explained there would be a brief hearing, they would be charged with running a brothel, fined, and freed a few hours later. It wasn't a big deal, he said. It was just part of the routine when the races were on - sex workers and sometimes pimps were arrested and released again.

When the women left the court Anna had an impulse to run, though she knew she had nowhere to go and no money. She was given no chance, anyway - her captors were waiting for them outside, holding the car doors open.

In Romania her mother read the headlines about the young women running a brothel in Ireland, her own daughter's name among them.

By that stage she'd already seen the photos the men had posted on Anna's Facebook account too - images of her naked or in ill-fitting lingerie, covered in bruises. Alongside them were comments in which Anna boasted about her new life and all the money she was making as a sex worker in Ireland. More lies, typed out by the men on their laptops.

Not only had her mother seen these photographs, the neighbours had seen them, Anna's friends had seen them. None knew that she had been trafficked and was being held against her will.

At first, her mother had tried to do something. But when she called her daughter there was never any answer.

"My mum went to the police in Romania," Anna says. "But they said, 'She's over the age of consent and she's out of the country, so she can do whatever she wants.'"

Eventually, Facebook deleted her account because of the indecent images and if anyone looked for her on social media it would have seemed that she no longer existed.

After the police raid, the four girls were moved around a lot, staying in different cities in different flats and hotels. But their lives remained as bad as ever - they continued to be abused at all times of day and night. Anna didn't think her situation could get any worse until she overheard her tormentors making plans to take her to the Middle East. She had to get away.

"I still didn't really know exactly where I was," she says. "But I knew that I had a better chance of escaping from Belfast, or Dublin, or wherever they had me, than escaping from somewhere in the Middle East."

She took the woman's flip flops and opened the door. She had to go very quickly and very quietly. She hadn't run or properly stretched the muscles in her legs for months, but now she had to move fast.

What saved her was the fact that men occasionally asked for one of the women to be taken to them, rather than visiting the flat where they were held.

Anna found these call-outs terrifying.

"You didn't know what crazy person was waiting for you or what they would do to you," she says.

"But any time I was out of that flat I would make mental maps of where I was. While they were transferring us from one point to another I would form maps in my mind - remembering the buildings, the street signs, and the things that we passed."

There was also one man - Andy, a convicted drug dealer on a tag - who never wanted to have sex, only to talk. A friend of his was trying to break into the brothel-keeping business and he wanted information.

"I had to gamble at that point," Anna says. "I didn't trust him, but he offered me a place where I could hide."

Relying on her incomplete mental map, Anna made it to Andy's address, only there was no answer. There was nothing to do but wait and hope that the pimps would not find her.

The gamble paid off. Andy had to return before midnight because of his tag. And he let her stay.

One of the first things Anna did was to call her mother.

The phone rang, and her mother's partner answered. As soon as he realised who was calling he began urging her never to call again, and never to visit. They'd received so many threats from the pimps and traffickers, her mother was now terrified, he said.

"So I said to him, 'OK, I'll make it easy for you. If anybody rings you and threatens you just tell them that I'm dead to you and to my mum,'" Anna says.

He hung up on her.

At this point, despite having no papers or passport, and despite her experience of the brothel raid - when she had been prosecuted instead of rescued - Anna decided to contact the police. And this time, fortunately, they listened to her.

It turned out that Anna was now in Northern Ireland, and she was told to attend a rendezvous with a senior policeman in a coffee shop.

"He took one of those white paper napkins and asked me to write down the names of the people who did this to me on it," she says.

When she pushed it back to him across the table she could see that he was shocked. He'd been looking for those people for years, he said.

A two-year investigation followed. Eventually Anna's former captors were arrested, but she was so worried for her own safety and her mother's that she decided she couldn't testify against them in court.

Another girl she'd known from the flat did give evidence, though, and the gang were convicted of human trafficking, controlling prostitution and money laundering in Northern Ireland.

Each of them was sentenced to two years. They served six months in custody before they were sentenced, then eight months in prison after being convicted, with the remainder spent on supervised licence.

They had already served two years in a Swedish prison on the same set of offences involving one of the same victims.

"I was happy that they were arrested but I wasn't happy about the sentences," she says.

"I guess nothing in this life is fair."

Where to get help

If you suspect someone is a victim of human trafficking, contact the police - call 999 if it's an emergency, or 101 if it's not urgent.

If you'd prefer to stay anonymous, call Crimestoppers on 0800 555 111.

If you want confidential advice about trafficking before calling the police, there are a number of specialist organisations you can talk to:

The Modern Slavery helpline 0800 0121 700, is open 24 hours a day.

If you think a child is in danger of trafficking you can contact the the NSPCC's helpline 0808 8005 000.

Later, with other women, Anna gave testimony to the Unionist politician, Lord Morrow, who had become so concerned about the increasing number of stories he heard about children and adults forced to work in brothels, farms and factories that he put forward a new bill to the Northern Ireland Assembly.

The Human Trafficking and Exploitation Act, passed in 2015, made Northern Ireland the first and only place in the UK where the act of buying sex is a crime. The act of selling sex, by contrast, was decriminalised.

Anna takes satisfaction from her role in this process.

"This law helps the victim and it criminalises the buyer and the trafficker," she says. "So it destroys the ring."

If even a small percentage of the men who used to pay for sex are now discouraged from doing so, that's still a success, Anna argues.

And people like her who are trafficked can live without fear, she says, because instead of being criminalised for being involved in prostitution, they're now more likely to benefit from support.

In 2017, it also became illegal to buy sex in the Republic of Ireland, where Anna's horrific ordeal began.

Her nine months in sexual slavery have left her permanently injured. Men damaged her body in the places where they penetrated her. Her lower back and knees constantly ache, and there's a patch at the back of her head where her hair stopped growing because it was pulled out so many times.

She suffers from terrifying flashbacks. Sometimes she cannot sleep, and when she does sleep she has nightmares. And sometimes she still smells that smell, the alcohol, mixed with the cigarettes and the sweat, the semen, and the breath of her abusers.

But she's looking forward now. She shopped the people who sold her body, she's helped change the law, and after years of not even speaking, her relationship with her mother is good.

"Me and my mum had to go on a really long journey to get her to understand what happened to me," she says. "She had to learn from me and I had to learn from her, but now we are fine."

Anna started a degree course in the UK but had to drop out because she couldn't afford the fees and didn't qualify for any funding. She now has a job in hospitality and it's going well.

"I would love with all my heart to return to my studies at some point," she says. "But for now I have to work, work, work, and keep focused."

All names have been changed.

Illustrations by Katie Horwich.

Slave, published by Ebury Press, is out now.

More from BBC Stories

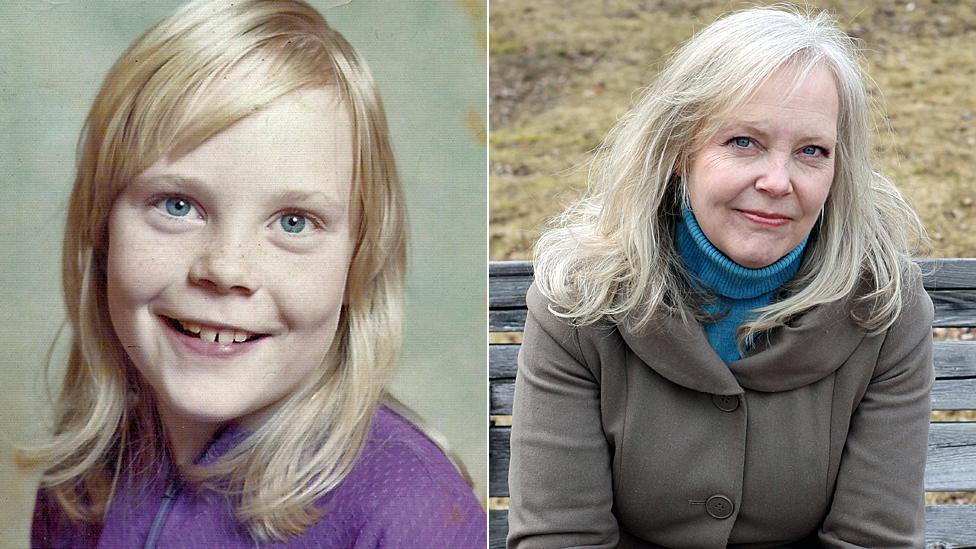

Pauline Dakin's childhood in Canada in the 1970s was full of secrets, disruption and unpleasant surprises. She wasn't allowed to talk about her family life with anyone - and it wasn't until she was 23 that she was told why.

Read: 'The story of a weird world I was warned never to tell'

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.