'Why I never want babies'

- Published

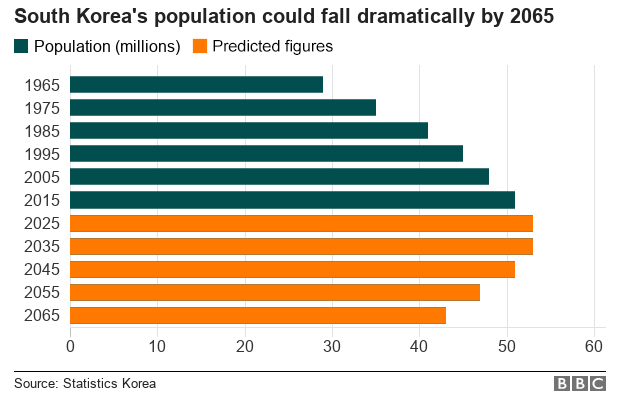

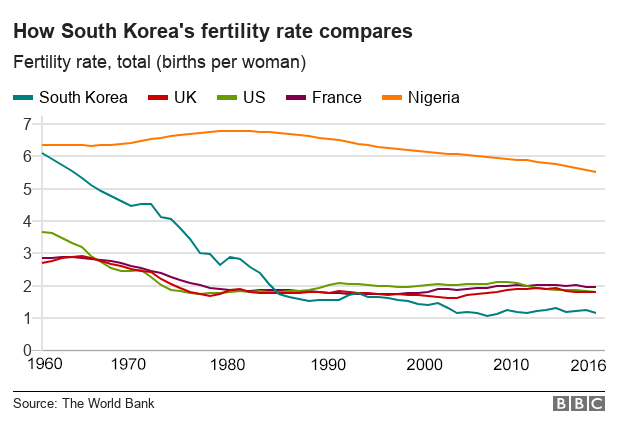

An increasing number of South Korean women are choosing not to marry, not to have children, and not even to have relationships with men. With the lowest fertility rate in the world, the country's population will start shrinking unless something changes.

"I have no plans to have children, ever," says 24-year-old Jang Yun-hwa, as we chat in a hipsterish cafe in the middle of Seoul.

"I don't want the physical pain of childbirth. And it would be detrimental to my career."

Like many young adults in South Korea's hyper-competitive job market, Yun-hwa, a web comic artist, has worked hard to get where she is and isn't ready to let all that hard graft go to waste.

"Rather than be part of a family, I'd like to be independent and live alone and achieve my dreams," she says.

Yun-hwa isn't the only young Korean woman who sees career and family as mutually exclusive.

There are laws designed to prevent women being discriminated against for getting pregnant, or for just being of an age where that's a possibility - but in practice, unions say, they're not enforced.

The story of Choi Moon-jeong, who lives in one of Seoul's western suburbs, is a powerful illustration of the problem. When she told her boss she was expecting a child, she was shocked by his reaction.

"My boss said, 'Once you have a child your child is going to be your priority and the company will come second, so can you still work?'" Moon-jeong says.

"And he kept repeating this question."

Choi Moon-jeong today

Moon-jeong was working as a tax accountant at the time. As the busiest time of the year approached, her boss piled even more work on her - and when she complained, he said she lacked dedication. Eventually the tensions came to a head.

"He was yelling at me. I was sitting in my chair and, with all the stress, my body started convulsing and I couldn't open my eyes," says Moon-jeong, her open, freckly face crumpling into a frown.

"My co-worker called a paramedic and I was taken to hospital."

At the hospital the doctors told her that stress was bringing about signs of miscarriage.

Find out more

Listen to Simon Maybin's report Not making babies in South Korea on Assignment, on the BBC World Service

When Moon-jeong returned to work after a week in hospital, her pregnancy saved, she felt her boss was doing everything he could to force her out of her job.

She says this kind of experience isn't uncommon.

"I think there are many cases where women get concerned when they're pregnant and you have to think very hard before announcing your pregnancy," she says.

"Many people around me have no children and plan to have no children."

A culture of hard work, long hours and dedication to one's job are often credited for South Korea's remarkable transformation over the last 50 years, from developing country to one of the world's biggest economies.

But Yun-hwa says the role women played in this transformation often seems to be overlooked.

"The economic success of Korea also very much depended on the low-wage factory workers, which were mostly female," she says.

"And also the care service that women had to provide in the family in order for men to go out and just focus on work."

Now women are increasingly doing jobs previously done by men - in management and the professions. But despite these rapid social and economic changes, attitudes to gender have been slow to shift.

"In this country, women are expected to be the cheerleaders of the men," says Yun-hwa.

More than that, she says, there's a tendency for married women to take the role of care-provider in the families they marry into.

"There's a lot of instances when even if a woman has a job, when she marries and has children, the child-rearing part is almost completely her responsibility," she says. "And she's also asked to take care of her in-laws if they get sick."

The average South Korean man spends 45 minutes a day on unpaid work like childcare, according to figures from the OECD, while women spend five times that.

"My personality isn't fit for that sort of supportive role," says Yun-hwa. "I'm busy with my own life."

It's not just that she is not interested in marriage, though. She doesn't even want boyfriends. One reason for that is the risk of becoming a victim of revenge porn, which she says is a "big issue" in Korea. But she's also concerned about domestic violence.

The Korean Institute of Criminology published the results of a survey last year in which 80% of men questioned admitted to having been abusive towards romantic partners.

When I ask Yun-hwa how men see women in South Korea, she has a one-word answer: "Slave."

It's clear to see how this feeds into South Korea's baby shortage. The marriage rate in South Korea is at its lowest since records began - 5.5 per 1,000 people, compared with 9.2 in 1970 - and very few children are born outside marriage.

Only Singapore, Hong Kong and Moldova have a fertility rate (the number of children per woman) as low as South Korea's. All are on 1.2, according to World Bank figures, while the replacement rate - the number needed for a population to remain level - is 2.1.

Another factor putting people off starting a family is the cost. While state education is free, the competitive nature of schooling means parents are expected to fork out for extra tuition just so their child can keep up.

All these ingredients have combined to produce a new social phenomenon in South Korea: the Sampo Generation. The word "sampo" means to give up three things - relationships, marriage and children.

Defiantly independent, Yun-hwa says she hasn't given those three things up - she's chosen not to pursue them. She won't say whether she intends to be celibate, or to pursue relationships with women.

Speak to South Koreans from older generations about the low fertility rate and the contrast in attitude is sharp. They see people like Yun-hwa as too individualistic and selfish.

I start chatting to two women in their 60s enjoying the stream-side park that runs through central Seoul. One tells me she has three daughters in their 40s, but none has had children.

"I try to instil patriotism and duty to the country with the kids, and of course I would love to see them continuing the line," she says. "But their decision is not to do that."

"There should be that sense of duty to the country," her friend chips in. "We're very worried about the low fertility rate here."

Yun-hwa and her contemporaries, the children of a globalised world, aren't persuaded by such arguments.

When I put it to her that if she and her contemporaries don't have children her country's culture will die, she tells me that it's time for the male-dominated culture to go.

"Must die," she says, breaking into English. "Must die!"

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.