Rocket woman: How to cook curry and get a spacecraft into Mars orbit

- Published

Can you guide a spacecraft into orbit around Mars and cook for eight people morning and night? Yes, if you get up at 5am, and your name is BP Dakshayani. Here the former head of flight dynamics and space navigation for the Indian space agency explains how she did it - and the housework too.

They became known as the Rocket Women or the Women from Mars. Four years ago, the picture of a group of women in saris celebrating as an Indian spacecraft successfully entered Mars orbit shone a light on the role played by women in the country's space programme - among them BP Dakshayani.

This picture of women at India's space agency celebrating the Mars orbit went viral

She led the team that kept an eye on the satellite, telling it exactly where to go, and ensuring that it did not deviate from its path.

One of her colleagues (also female) described the task as like hitting a golf ball in India and expecting it to go into a hole in Los Angeles - a hole, moreover, that was constantly moving.

It was a tough job made tougher by the responsibilities of an Indian wife. But her strength of will had become obvious many years earlier, when the girl from a "quite traditional, conservative and orthodox" family set her sights on a career in science.

As a child growing up in the 1960s in Bhadravati, a town in the southern state of Karnataka, her father had initially encouraged her interest, and it flourished. There was only one woman in the town who had studied engineering, and Dakshayani would run out to see her whenever she passed their house.

Find out more

Listen to Rocket Woman or download the podcast

My Indian Life is a new podcast on the BBC World Service, presented by Kalki Koechlin and produced by Geeta Pandey

Back then educating girls was not seen as a priority and it was pretty unusual for them to go to university, but her father - an accountant with impressive maths skills - wanted her to study. So she signed up for an engineering degree and graduated top of her year.

But then a disagreement arose. Dakshayani wanted to go on to take a Master's degree. Her father, however, thought that a BSc was sufficient. In the end, Dakshayani got her way - and once again graduated with top grades.

After that she took a job in a college teaching maths, but her interest in space and satellites was deepening. One day she saw an advertisement for a job at Isro, the Indian space agency. She applied - and was hired.

It was 1984 and Dakshayani was put to work on orbital dynamics. Today she is a specialist in the area, but at the time she had to work hard to understand the basics.

The team tracking the orbiter hard at work

She was also assigned to do computer programming, but there was a slight problem there - she had never actually seen a computer. In those days that was not really unusual. Not many people had computers and there were no smartphones or tablets. But she had books. So every day, after work, she would go home and read books on computer programming to get up to speed.

Before long, Dakshayani had other kinds of homework to do as well.

A year after she began working at Isro, her parents arranged her marriage to orthopaedic surgeon Dr Manjunath Basavalingappa - which meant that she suddenly had a household to run.

At the office, she did complex calculations and computer programming to guide satellites. At home, she looked after her large family that included her parents-in-law, her husband's five siblings and within a few years - their own two children.

"I used to get up around 5am because I had to cook for seven, eight people and it was not easy," she says." Also, our food habits are such that we need chapatis (hand-made bread) which take time to make. So I would cook for the whole family and then come to office."

Once in the office, she says, there was little time to think about home and she would just about manage to call home once in the afternoon to find out how the children were doing. In the evenings, she would get back home and start cooking again.

It was tough, she admits.

Some of her relatives assumed she would quit her job, she says, "but I am not a person who gives up easily."

"Also, my father used to say that we should try until the end. Even when it comes to technical things, if I don't understand something, I read it many times until I do."

Sometimes she would go to bed at 1am or 2am, she says, and get up again at 4am to work.

You may also like:

The women scientists who took India into space

Hidden figures: How Nasa hired its first black women 'computers'

But Dakshayani is not complaining. Far from it. Her voice is full of enthusiasm as she talks about how she juggled home and work life, how much she enjoyed her work and how solving problems gave her happiness.

It must have helped that she actually enjoys cooking.

"I keep doing some small small modifications and try making new things. I say cooking is similar to coding - just as one small change in the code will result in a different number, similarly a small change in ingredients will result in a different taste," she says.

One evening, Dakshayani invites me into her home in a quiet Bangalore neighbourhood to meet her husband. As she brings out tea and delicious snacks, the couple talk about the decades they've spent together, about how they have supported each other in tough times and how their relationship and respect for each other has grown over the years.

In the initial years, Dakshayani says her husband couldn't understand what she actually did. "Sometimes I would go to work on Saturdays and he thought maybe that was because I was not doing my work properly," she says.

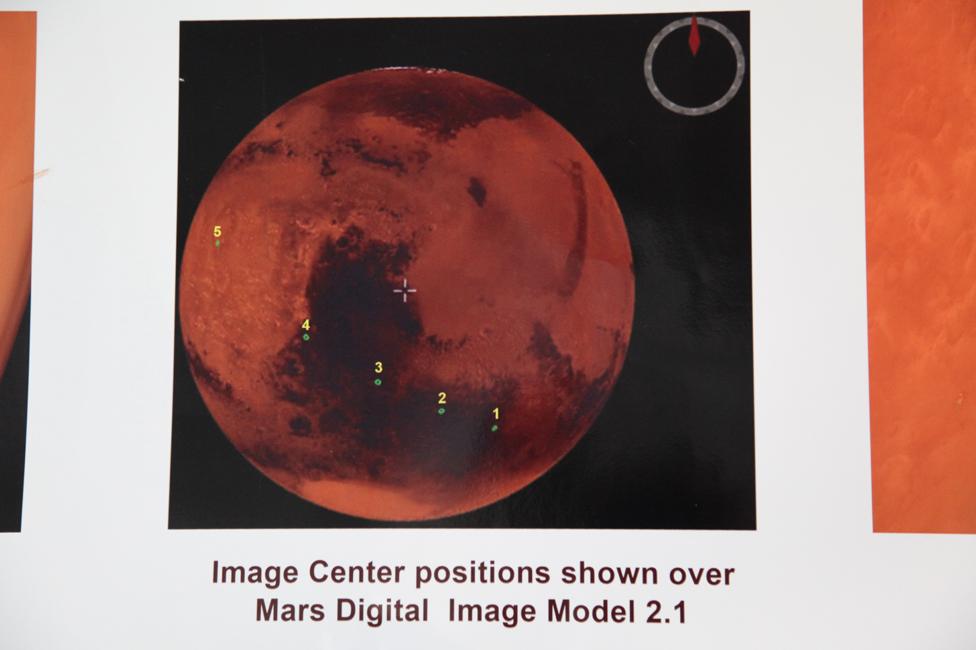

One of the first images of Mars sent back by the Indian orbiter

But gradually he came to understand that satellites dictated his wife's work schedule, and "would not come when we wanted". Today, Dr Basavalingappa says he is incredibly proud of his wife and what she has achieved by her hard work - the Mars mission, for example, and the "space recovery project" where Dakshayani calculated how to ensure that a space capsule returning to Earth would not burn up on re-entry to the Earth's atmosphere, and could be safely recovered at sea.

Asked to rate their lives with each other, Dr Basavalingappa says he would give her "10 out of 10".

Dakshayani laughs and says she will give him only 9.5. "Because you never ever found an occasion to assist me in the housework."

In a traditional Indian family set-up, women are expected to bear most of the burden - and in most homes they do it uncomplainingly. Dakshayani is no exception.

Dakshayani (right) with her husband, Dr Manjunath Basavalingappa

Dr Basavalingappa explains that as a doctor, his working day often stretches up to 18 hours, while his wife mostly worked office hours. Dakshayani seems satisfied with this explanation.

The home front, she says, is no longer so busy. Her son and daughter - both engineers - have grown up and moved to the US to work.

I ask her about her post-retirement plans, but it seems full retirement is not on her agenda.

She wants to continue studying Mars. She lists the differences and the tremendous similarities between Earth and the red planet.

The planet that made her an inspiration to many young Indian girls is one, she says, that she would love to live on. That really would make her the Woman from Mars.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.