'Sorry, Dad - I'm thinking of getting a German passport'

- Published

BBC radio presenter Adrian Goldberg is entitled to a German passport - and in a post-Brexit world it might come in very useful. But his family history makes him think twice about taking this step.

When I played war games as a youngster in front of the block of flats where I grew up in Birmingham, the other kids would sometimes make me act out the role of the Germans.

They knew my dad was a "Jerry" and were cheerfully oblivious to the irony that, as a Jew, he was forced to flee the Fatherland and was later called up by the British Army to fight against Germany in the latter stages of World War Two.

I soon gave up trying to explain the nuances of Nazi politics and usually suggested we kick a ball around instead.

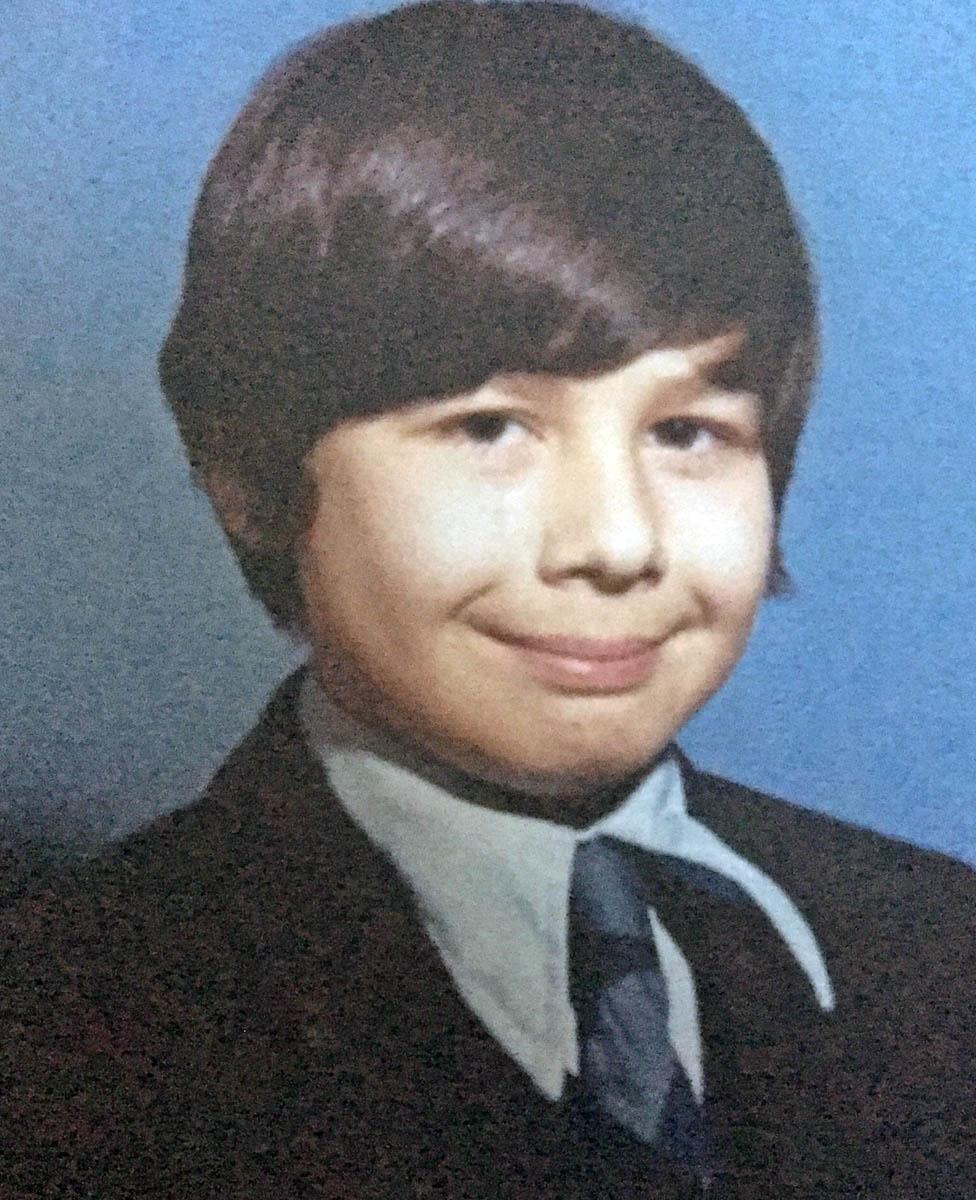

Adrian Goldberg as a boy

In the decades since, the idea that I might one day consider exercising my birthright by applying for German citizenship would have been utterly laughable.

I'm British through and through, and while I'm not the kind of yob who sings about "two World Wars and a World Cup too", I can't deny that a rare England football victory against Germany always brings a special satisfaction.

Brexit, though, has changed the way I think. Not, I should stress, from any political or philosophical standpoint. Britain, in all its crazy, kind-hearted, perverse, creative, and sometimes self-destructive glory, is unquestionably the place I belong.

But although I still love my country as much as I did before the referendum, there's a question I'm having to seriously address for the first time in my life.

Should I get a German passport?

Find out more

Adrian Goldberg's series for BBC Radio 4's PM begins on Christmas Eve and continues on 26, 27 and 28 December 2018. You can catch up afterwards on iPlayer.

A film about Adrian's story will be broadcast on Inside Out on BBC One in the West Midlands at 19:30 on January 14 2019

A couple of friends tell me it's a "no-brainer". They point out that like any EU citizen, I'd have the right to work and travel freely across 27 nations without any visa requirements.

That might well come in handy if I decide to wind down my radio career on an English language station in, say, Majorca.

Even more importantly, my three young daughters would share the same entitlement.

But as the son of a refugee who owes his life to this country, it's not such a straightforward calculation.

Adrian Goldberg's father Rudy in the British Army

As my mate Mike succinctly put it: "You'd be a traitor, wouldn't you?"

And then, metaphorically kicking me while I'm still on the ground, he asks: "Whatever would your dad think?"

Unfortunately, I can't find out. My father died six years ago. But even my mom admits, "He probably wouldn't like it."

Adrian Goldberg's parents, Rudy and Kitty, on their wedding day

Seeking inspiration, I head to the Jewish cemetery in Birmingham, where dad is buried.

Rudy Goldberg had a great life in this country, fathering four kids. Eventually he had a brood of grand- and great-grandchildren.

None of this would have been possible without a government backed scheme called Kindertransport which allowed about 10,000 German-Jewish youngsters to settle in Britain just before the war.

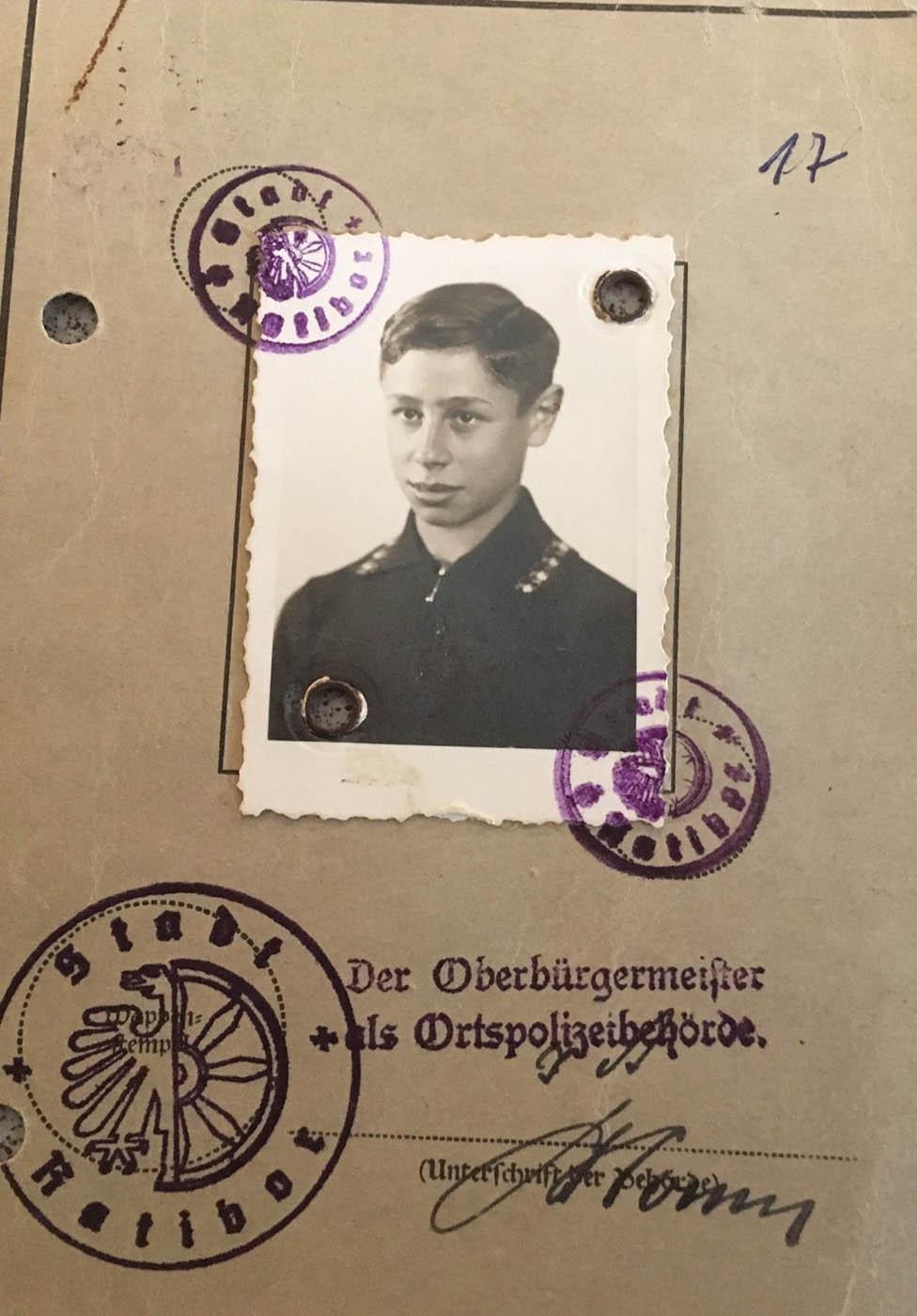

Rudy Goldberg’s papers allowing passage from Germany

I can't imagine the heartache of his parents, Ruth and Julius, as they waved off their two young sons, sending them to a foreign country whose language they couldn't speak, to be adopted by strangers. But it was a decision that saved their children's lives.

Other members of the family were not so fortunate.

Ruth and Julius

Close to my father's grave, there are brass plaques on the wall of the Ohel (or prayer room) commemorating his nine close relatives, including Ruth and Julius, who perished at Auschwitz.

This visit to the graveyard only sharpens my dilemma. Sure, I can get a passport which might conceivably make life easier for myself and my children. But only if I adopt the nationality of the country that murdered most of my dad's family.

Easy, eh?

To get a sense of what my father's contemporaries would do, I head to a meeting of the Association of Jewish Refugees at the New North London Synagogue to meet other Jews who, like my father, arrived on the Kindertransport.

Ruth Jacobs, from Nazi-occupied Vienna, tells me with a twinkle in her eye how she was given a home by a wealthy English family, who were struggling along with too few servants.

She persuaded them to offer her mother a job in the kitchen (even though she was a dreadful cook) and her father a position tending the garden (despite the fact that back home they lived in a flat).

Both parents arrived from Austria just weeks before the outbreak of the war.

Ruth Jacobs

It's an unlikely, slightly comical story of survival, and not surprisingly, Ruth concludes by saying she could never contemplate taking a German passport.

Other survivors tell me more harrowing stories, including Ralph Stanton who, in an echo of my father's story, escaped with his younger brother but lost the rest of his family in the death camps.

He says that despite the Holocaust, he applied for a German passport several years ago, when his British one was due to expire, simply because it was easier.

"Maybe I've got less of a conscience than other people," he chuckles.

Then, more seriously, he looks at me and growls, "Get it while you can."

I reason that if one of these survivors can so readily sign up for a German passport, then maybe so can I.

But then the doubts start to creep in. I've heard a lot in the last few years about the rise of the Alternative fur Deutschland, an anti-Islam party, which is now the third largest in the German parliament.

Have the Jews simply been replaced by the Muslims as a persecuted minority?

Beatrix von Storch

To find out, I take a trip to Berlin, where I put the question directly to the AfD's deputy leader, Beatrix von Storch, the grand-daughter of one of Hitler's ministers, who tells me her party is simply concerned with upholding German values.

As for any echoes of Nazism in their language, she bristles: "If you put that in the line of the Third Reich, then you are completely stupid, and have no idea what happened in the Holocaust."

Elsewhere in Berlin, there are cheerier signs. Dekel Peretz, an Israeli immigrant, and his wife, German-born Jewish convert Nina, are successfully rebuilding a faith community around an old synagogue in the diverse Neukoln district of the city.

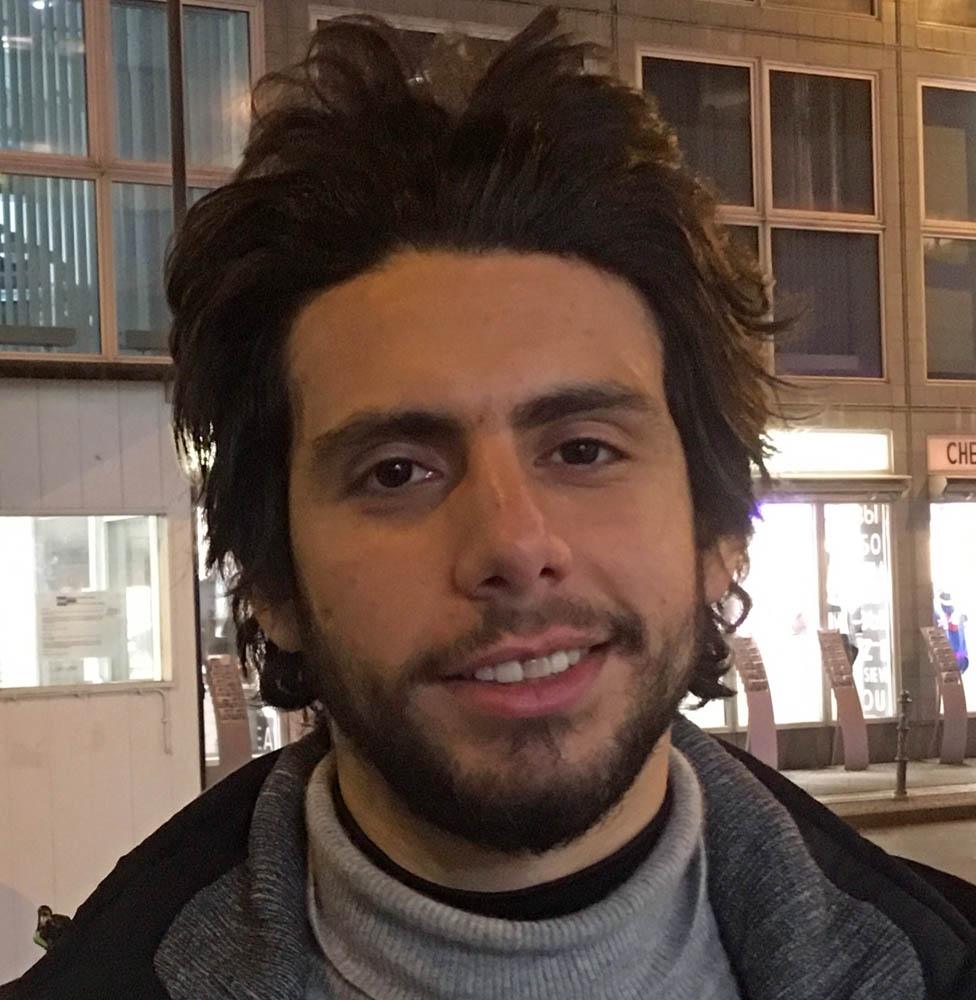

Then there's Nafee Kurdi, a smiling Syrian refugee with a shock of curly black hair who has become a tour guide at Checkpoint Charlie.

Nafee escaped Damascus after his school was bombed, killing several of his classmates, and he's among the estimated one million asylum seekers allowed to settle in Germany by Chancellor Angela Merkel since 2015.

Like me, Nafee marvels how a country from which my father was once forced to flee has now become a place of sanctuary.

"It's definitely a remarkable turnaround," he says. "It's because everyone feels guilty about it [The Holocaust] and doesn't want it to happen again."

I'm still musing on this when I arrive in Raciborz, the town my Dad had to leave in 1939. The memory was so raw that he never returned.

In the post-war carve up of Eastern Europe, this quiet rural outpost of Germany was gifted to Poland, and the existing German inhabitants were forced to leave becoming, in their turn, refugees.

Raciborz train station, where Rudy left for the UK

Standing in the Jewish graveyard, now neglected and overgrown, where my great-grandmother is buried, I get an eerie feeling, and when I walk up to the main town square I have the closest thing in my life to an epiphany.

I'm suddenly conscious of standing on the streets where my dad would have played as a boy and where at least two generations of Goldbergs brought good cheer to the local community by brewing beer and running pubs.

These were people who thought they were members of a prosperous and established community. Jews, after all, had been peacefully settled in this region for three centuries.

When the Nazis came that counted for nothing and they simply had no escape route.

And that's why, in some ways against my gut instincts, I will be applying for German passport.

Let's be clear: I'm not comparing post-Brexit Britain to pre-war Germany. Nor do I feel remotely German.

It's rather that my family history warns me that even well-ordered, apparently stable societies can quickly break down. Neighbour can be set against neighbour.

I don't honestly expect that will ever happen in the UK, and even when I get my German passport there's no way I'll be giving up my British one.

But if intolerance and extremism should ever get a foothold here, who could blame me for wanting to protect myself and my family and sadly bidding "Auf Wiedersehen" to the country I call home?

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.