The women who love mummies

- Published

Women explorers played a major part in the UK's fascination with Egyptian mummies a century ago, and girls who - much later - visited their collections in provincial museums are among today's up-and-coming archaeologists. Samira Ahmed looks at female influence in the mummy world.

It was a "light bulb moment - like being teleported back into ancient Egypt" says Danielle Wootton, remembering her excitement at seeing Bolton Museum's Egyptian mummy for the first time.

"Suddenly there were these people that lived hundreds of years ago and in a very different way to how I lived my life in Bolton. It was just amazing to think that this other world existed, this past - who were these people and what kind of language did they speak?"

In time Danielle became a professional archaeologist and an expert on Channel 4's Time Team.

Later, the same thing happened in Macclesfield, 30 miles to the south, when Rebecca Holt walked into the city's West Park Museum and saw the mummy case of a 15-year-old temple girl.

"I was probably about five and remember seeing the mummy case for the first time and it was just sheer fascination. 'Mum, what's this, what's this?' And my fascination never went away," she says.

She kept going back and at 14 was a museum volunteer, spending hours there after school. A mentor, honorary curator Alan Hayward, taught her how to read hieroglyphs and handle objects. Now 24, she's just finished a master's degree in archaeology at Oxford University.

The passions awakened by the mummies in these two young women are inherited in a very direct way from two women who lived in their localities a century earlier, and whose collections the museums were built to house - Annie Barlow in Bolton and Marianne Brocklehurst in Macclesfield.

In fact, there is an even stronger link than this between Danielle Wootton and Annie Barlow. Barlow was the daughter of a wealthy mill-owner, and Danielle's own grandmother and aunt worked in the Barlow and Jones family mills.

Annie Barlow

It was the money earned from the mill - which spun Egyptian cotton into Lancashire cloth - that enabled Barlow to go and explore Egyptian tombs.

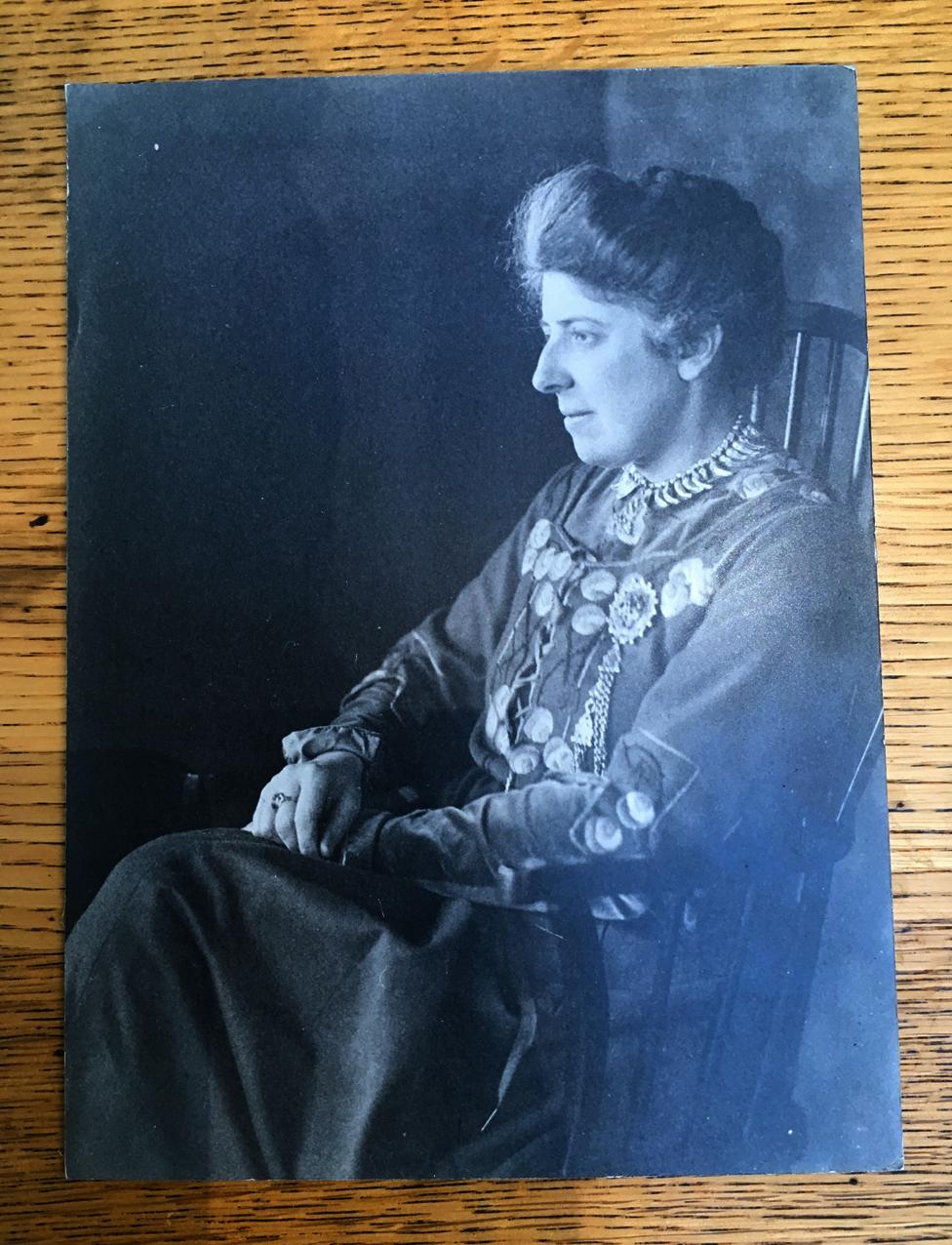

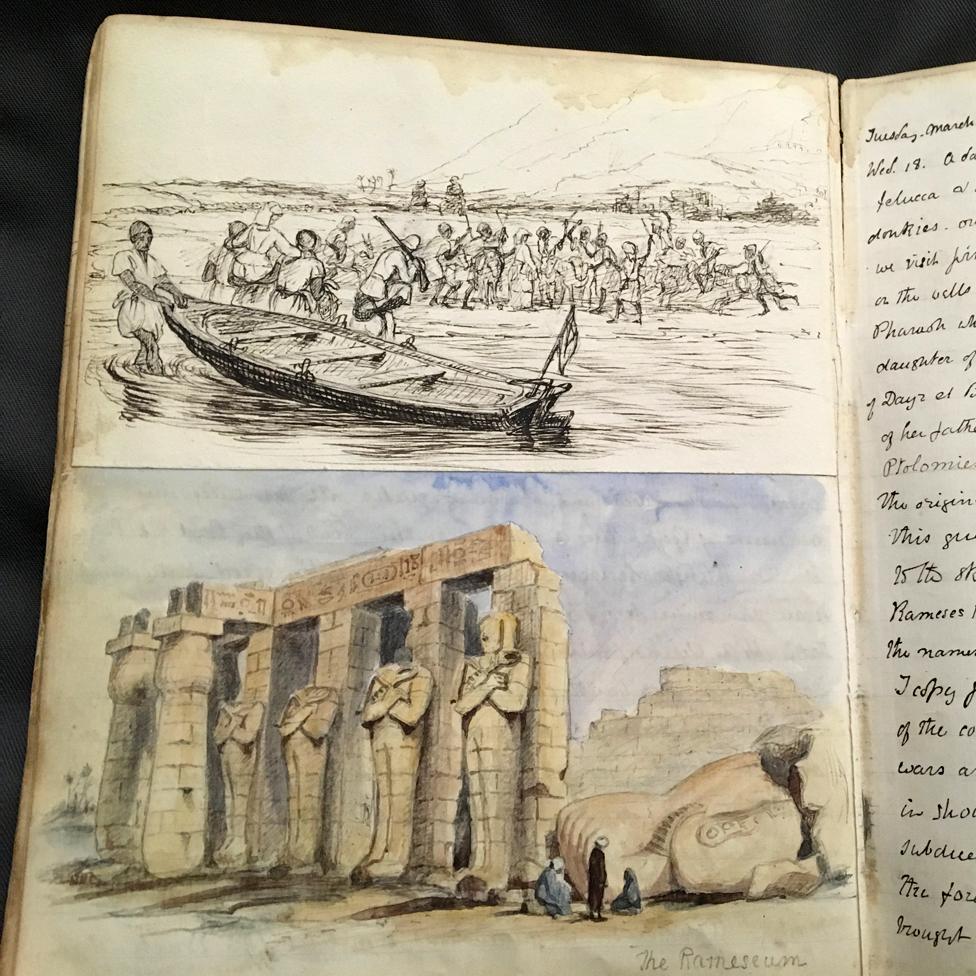

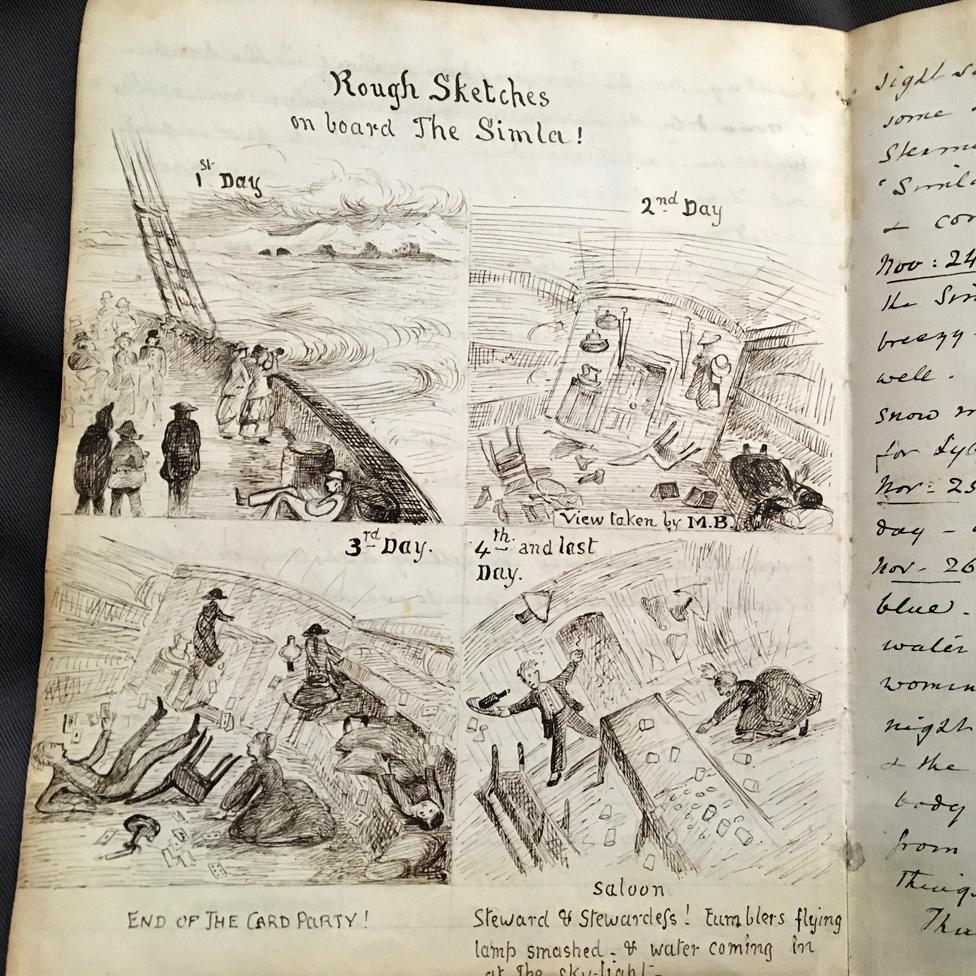

Marianne Brocklehurst, meanwhile, came from a silk manufacturer's family. As well as funding her own travels she paid out of her own pocket for the construction of the West Park Museum, where Rebecca found her inspiration. Her legacy includes not just the objects she brought back from Egypt but her detailed diaries and sketches of her trips down the Nile, which are some of the only records of tomb sites before they were disturbed.

Marianne Brocklehurst's diary

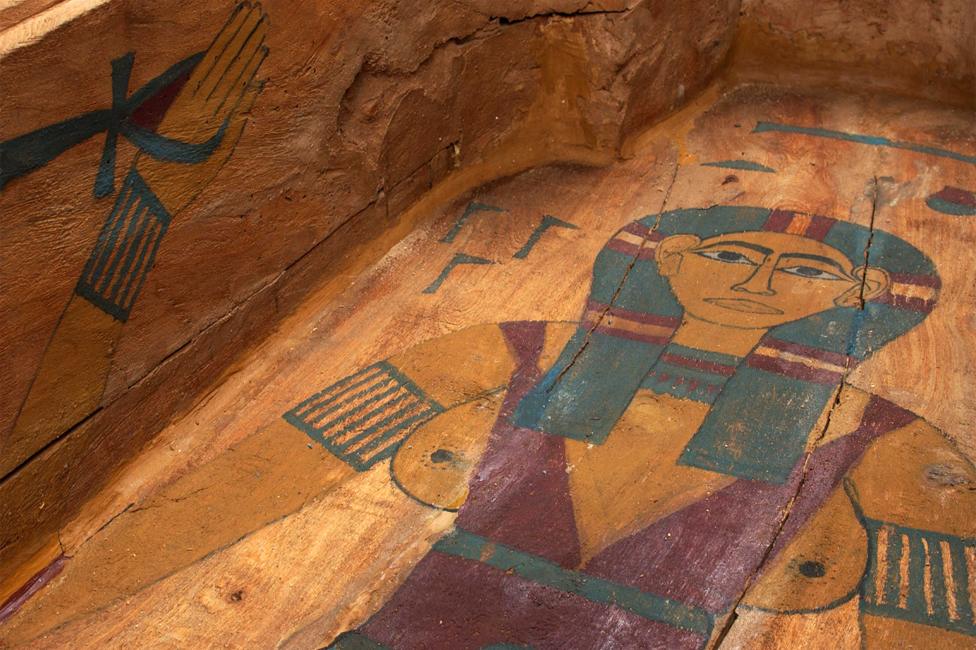

But there is a third northern mill heiress who made a major contribution to the UK's mummy mania - Amelia Oldroyd, whose finds are catalogued in leather-bound record books in the archive of the Bagshaw Museum in Batley. She was one of the first to explore a burial chamber at Abydos - now recreated in the museum - after it was opened in 1900 for the first time in 4,000 years.

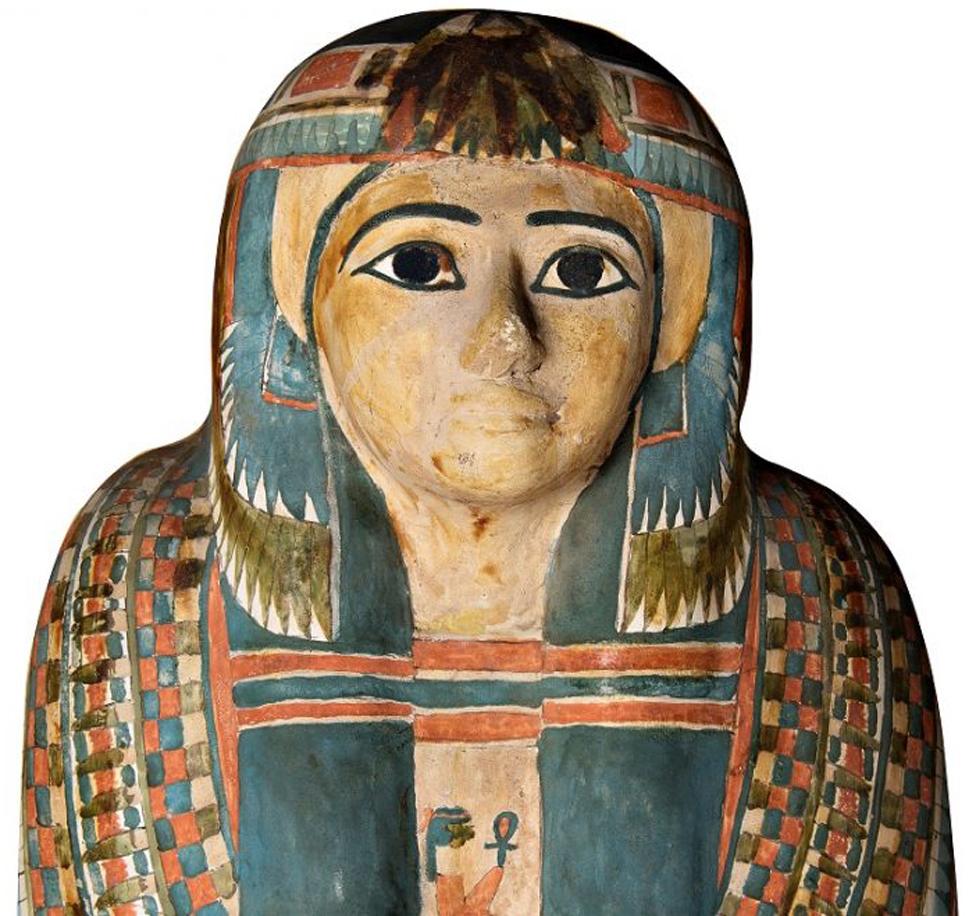

At a time when male collectors were throwing textiles aside in their hunt for large mummy cases and gold objects, Amelia brought back a rare intact cartonnage - a mummy wrapping made of papyrus with a painted representation of the dead person's face.

Find out more

Listen to Samira Ahmed's documentary, The Victorian Queens of Ancient Egypt, on Radio 3, on Sunday 3 February at 18:45

According to a third young female archaeologist, Cairo-born Heba Abd El Gawad, the female explorers had a distinctive approach, focusing not just on the grand tombs but on the intimate small portable objects. (One reason, possibly, why they tended to be dismissed as amateurs by contemporary male archaeologists.)

"Unlike displays that we see today, where there is so much focus on gold, royal figurines, everything that is very glittery, I think you can tell from their collecting patterns that they were also interested in the daily life of ordinary people," Heba says.

Cartonnage case of Takhenmes

She points also to their collections of cartonnage face wrappings. "There is this intimacy in the mummy face. You can see the eyes, it's looking back at you. You can see the human being in there."

In the present day, Danielle and Rebecca also focus on small portable antiquities and what they reveal about lived life - the make-up containers, the jewellery, the small statues. Rebecca's favourite object in the display in Macclesfield is a six-inch statuette of a queen, Queen Ti, who is wearing large ornate wig and carrying a lotus flail.

Rebecca Holt, and behind her, on the left, the figurine of Queen Ti

"It's one of the first artefacts whose hieroglyphs I tried to translate, so that's quite special to me," she says. "The carving itself is really magnificent. I love Queen Ti - how powerful she was and how much influence she had."

For Heba, 26, who grew up looking at the pyramids and thinking about the human labour forced to create them, while reading books on the ancient Egyptian world bought for her by her father the Victorian women themselves hold a complex fascination. They were Egyptology pioneers, who used public subscription to fundraise to bring cultural enrichment back to ordinary people. But they were also colonial looters.

Heba Abd El Gawad (left, with Samira Ahmed) has studied how the British Victorians collected and distributed their Egyptian finds. She co-curated an exhibition in London in 2016 about the ancient Egyptian afterlife, drawing on these Northern museum collections.

The diaries and lectures of these Victorian women capture the adrenalin rush of discovery. Amelia Edwards, another Victorian pioneer, founded the Egypt Exploration Fund which made possible the excavations of the famous male Egyptologist, Flinders Petrie. On one occasion she wrote about receiving a note at their camp from an artist travelling with them: "Please come immediately - I have found the entrance to a tomb. Please bring some sandwiches."

On rushing to join him Amelia wrote: "All that Sunday afternoon we toiled upon our hands and knees as if for bare life, under the burning sun. More than once, when we paused for a moment's breathing space, we said to each other: 'If those at home could see us, what would they say!'"

Torso of a princess, acquired by Flinders Petrie while working for the Egypt Exploration Fund

But the Victorian women were enthusiastic participants in a kind of Wild West of collecting in the Nile valley, battling against the deeper pockets of the British Museum, the Louvre and the Penn Museum of Philadelphia, bargaining with local dealers and officials. Bribery and theft were routine.

Marianne Brocklehurst's diary jokes about smuggling antiquities out. The reason that mummy case in Macclesfield is empty is because she discarded the body, possibly overboard from her boat, into the Nile, worried the smell might give away her theft.

Heba says, "Maybe for me it can be doubly sensitive being Egyptian and how we perceive the body today. Even during Pharaonic time there were texts that totally condemned tomb robbers and anyone who fiddles with mummies or does unwrapping just to take the jewellery and amulets. That was a huge offence in ancient Egypt."

The goddess Nut, painted on the inside of a coffin

Heba believes Egyptology museums should be honest about the provenance of their collections. The new display for Brocklehurst's mummy case in Macclesfield's Silk Museum - where it has been moved from the West Park museum - makes no mention of the discarding of the body, or the fact that it was smuggled out. Mummified hands sit in a glass case with no labelling.

'I don't want to make it sound like I'm pro-returning everything. That's not what I'm after," says Heba. "But what I'm after is trying to [make people think] what makes it acceptable?" It would never have been acceptable, she points out, to exhibit British human remains this way.

Marianne Brocklehurst's diary

Rebecca feels she can still see Marianne Brocklehurst as a heroine, while acknowledging that her diary shows the unpleasant, even racist colonial attitudes of the time. Her favourite passages recount how Brocklehurst sacked the Egyptian chef on her Nile houseboat who was beating the kitchen maid, then promoted the maid to his job. "Her priority is to protect this woman. And it's just, 'You know, we don't need this man. She [the maid] can do great.' She was just fiercely protective of the women in her life."

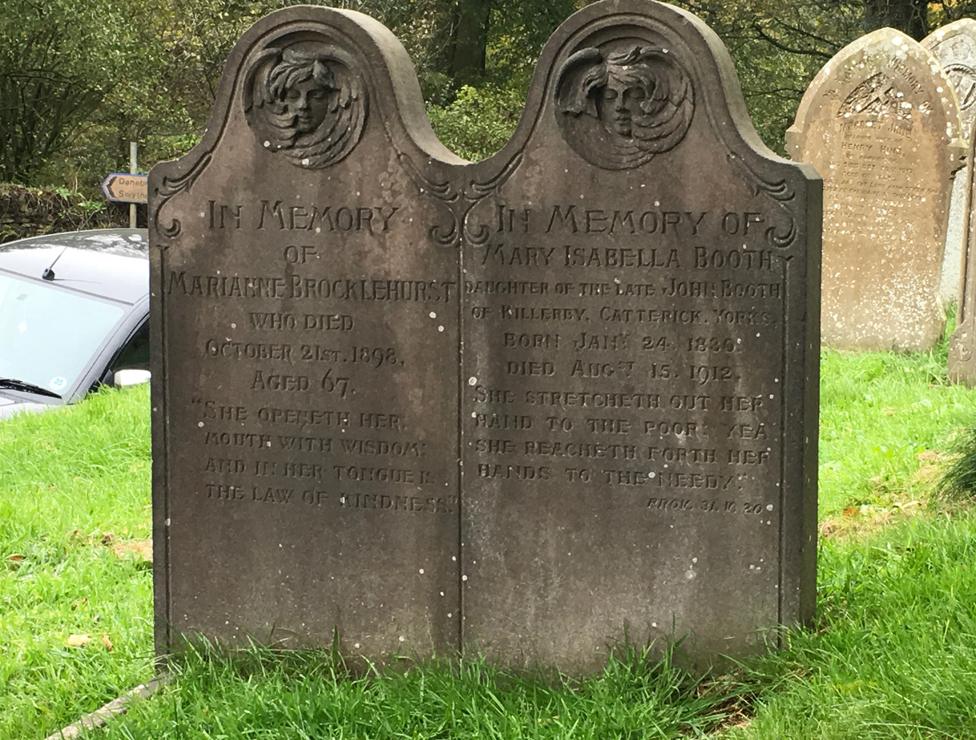

The double grave of Marianne Brocklehurst and Mary Isabella Booth, believed to be her lesbian life partner, at Wincle, near Macclesfield

The dilemma now is whether local councils hit by years of central government funding cuts, can see a value in investing in updated displays and expertise for these Egyptology collections. In a growing number of the 150 museums across the country which hold such collections there is a battle to even keep them on display. Northampton Council's controversial sale in 2014 of the ancient Egyptian Sekhemka statue (gifted to them in 1870) to raise funds, caused international outrage in the museum world, especially in Egypt. Arts Council England withdrew the city museum's accreditation.

"I guess I'm just really, really thankful that West Park Museum was here," says Rebecca Holt. The museum is currently rarely open.

Rebecca Holt at West Park Museum

Budget cuts have hit Dewsbury museum where Amelia Oldroyd's collection was held for many years. It closed in 2016 and Bagshaw Museum in Batley, where the artefacts now are has no specialist curator and operates restricted opening hours.

Bolton Museum shows what can be done with vision and money. Its sensitively refurbished Egypt Gallery tells the story of Annie Barlow. Signage in the beautifully reconstructed tomb of Thutmose III, where the unidentified male mummy is now on display, makes clear that keeping human remains is a dilemma. There is equal focus on the life of ancient Egyptians, not just their death.

Danielle Wootton looks at the crowds of children and families packing "Bolton's Egypt" gallery in Bolton Museum. "I'm really, really happy to see it because that's how I felt years ago. And it's really great to see that it's continuing to inspire generations."

You may also be interested in:

Seaweed has been hailed as a new superfood, and it's also found in toothpaste, medicine and shampoo. In Zanzibar, it's become big business - and as it has been farmed principally by women, it has altered the sexual balance of power.

Read: The crop that put women on top in Zanzibar

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.