'Salman Rushdie radicalised my generation'

- Published

It's Valentine's day 1989. Margaret Thatcher is prime minister and Kylie, Yazz and Bros are making noise. Far away, Iran's supreme leader issues a fatwa demanding the death of British author Salman Rushdie - and the effect on young Muslims in the UK is huge.

Alyas Karmani was soaking up everything student life had to offer. He'd grown up in Tooting, south London, in a traditional Pakistani household, his father a bus driver and trade unionist. Religion was an important part of Alyas's upbringing but not something he was particularly interested in.

"We were obedient to our parents. We'd go to the mosque when it was required but we had a clandestine double-life existence," he says. "We were partying, smoking weed, going out with girls and doing everything we could possibly do."

So when it was time to choose a university, Alyas ran away from his Pakistani Muslim identity and headed 400 miles north to Glasgow. "I was running as fast as possible. I was a 'self-hating Paki'. I didn't want brown friends. All my friends were white liberal mainstream types. That was my crowd."

In Glasgow, Alyas would become an important fixture on the student scene. He ran club nights and loved music and dancing. "I had a wonderful time and then something really inconvenient happened in 1989."

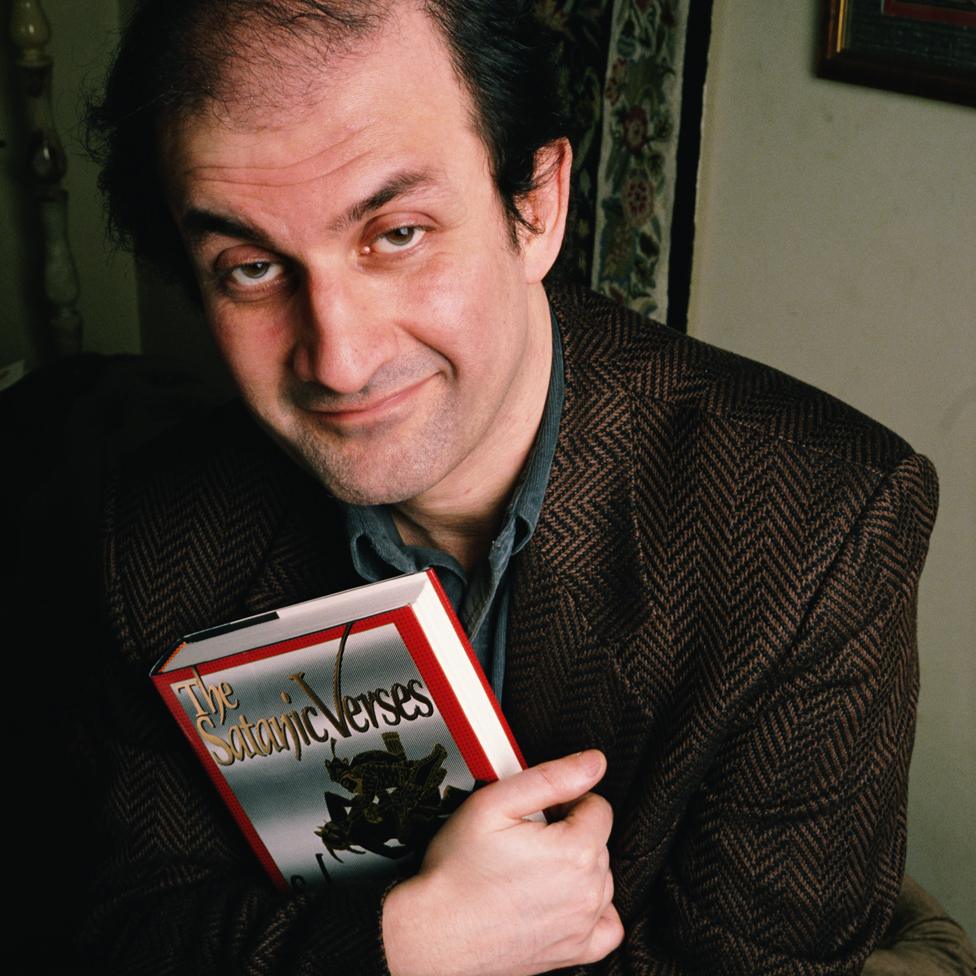

Alyas Karmani in June 1990...

That inconvenience was Ayatollah Khomeini's fatwa - imposed on Salman Rushdie for his novel, the Satanic Verses, which was widely considered blasphemous in the Muslim world. While Alyas didn't think Rushdie should die, he also didn't think The Satanic Verses was OK. Now he found himself being blamed for a fatwa that had nothing to do with him.

"I thought these friends understood and accepted me but now they were pointing fingers. The conversations went like this: 'What's wrong with you people? Why are you doing this? Why have you put a death threat on Salman Rushdie? What side are you on? Are you with us or against us?' It was really as stark as that."

Alyas had felt uncomfortable going to mosques, which back in the 1980s were run almost exclusively by older South Asian men whose first language was not English. So Alyas went searching for Islamic guidance from younger, English-speaking Muslims and found it. Under their influence, he reconnected with the faith of his parent's generation, but took it in a much more radical direction - the focus was on global Muslim identity rather than personal morality or spirituality.

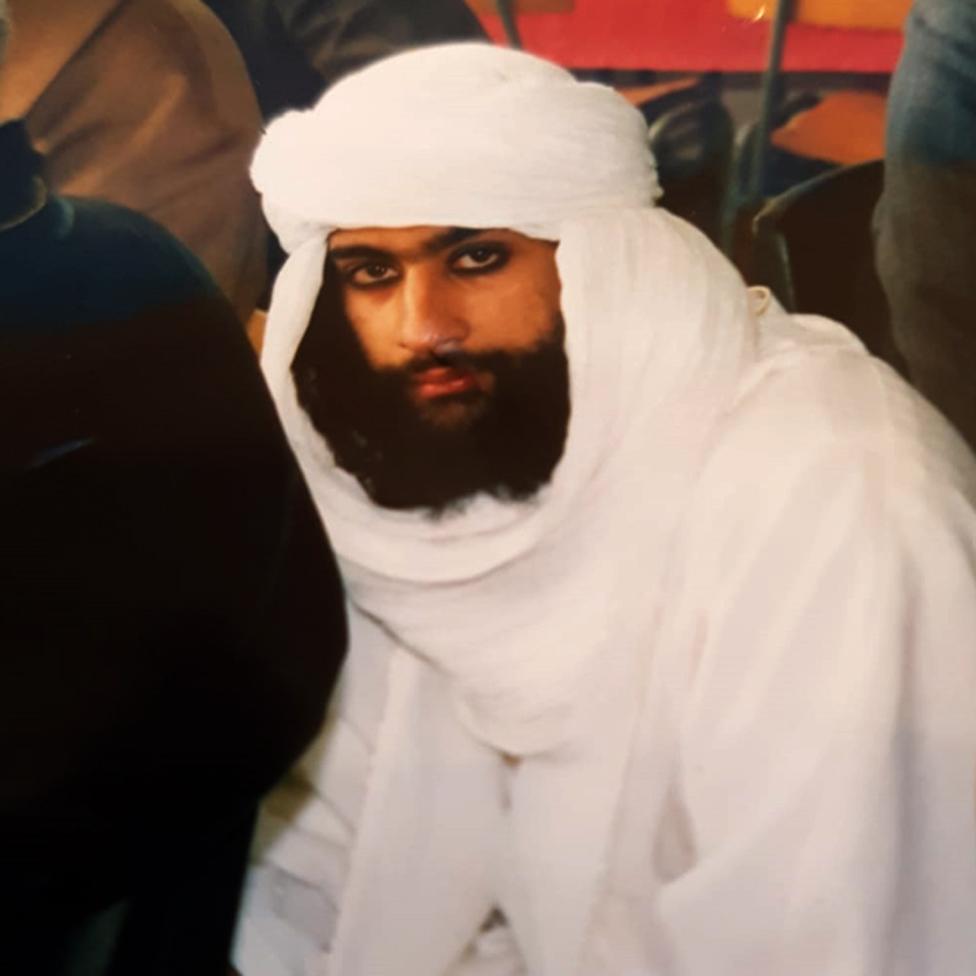

... and six months later, in December 1990

"It was a counterculture. It had a dress code and a language. I left my non-Muslim friends and when I left university, I completely devoted myself to the movement," he says.

"It all started with the publication of the Satanic Verses and how people pushed me away. That's why I always say I am one of Rushdie's children. I was radicalised by white liberals."

The Salafi school of thought Alyas became part of is more puritanical than traditional South Asian Islam, and has overt political leanings. Some of the people Alyas associated with ended up fighting in Bosnia, as members of the Bosnian army. He never made it to the battlefield, he says because his skills "were in promoting ideology".

Find out more

Listen to the 10-part series, Fatwa, from BBC Radio 4, or download the podcast

The Satanic Verses: 30 Years On will be broadcast on BBC Two at 21:00 on Wednesday 27 February

Today, Alyas has softened his approach. "Back then we only saw binary options: good or bad. With or against. Halal or haram. Now I prefer shades of grey," he says.

He remains a devout Muslim who champions "the middle way". He is an unconventional imam and psychologist. He offers his congregations in Huddersfield and Bradford advice on everything from sex and relationships to mental health.

Ed Husain was a few years younger than Alyas when The Satanic Verses was published. Still at school, he was excited when his father took him to Hyde Park to protest against the book.

Burning the Satanic Verses in Bradford

The demonstration saw coachloads of Muslims travel from Glasgow, Bradford, Birmingham and elsewhere - altogether about 20,000 arrived. Communal prayers, which had mostly been reserved for within the mosque, were now taking place in London's public places. Effigies of Rushdie were burnt and placards threatening violence were common.

When Ed's father saw people burning The Satanic Verses in Hyde Park, he decided it was time to leave.

At home, Ed's father told him they weren't "that kind of Muslim" but the protest had piqued Ed's interest. He began to attend East London Mosque without his father and was inspired by English-speaking imams who were happy to talk politics.

'I came out as Muslim'

Salman Rushdie was a hero for Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, then a journalist on the New Statesman - not only for his writing but also because he had spoken publicly about racism in Britain. So she read the book.

"I wasn't offended. I'm not that kind of Muslim but I did wonder, 'Why are you doing this?' It read to me as deliberately provocative," she says.

When Muslims started burning the book, many of Yasmin's white friends were disgusted. "It very quickly became 'them and us'. At dinner parties, if I said anything about disagreeing with Rushdie, people would walk out! That's how difficult it became."

Yasmin describes what followed as "a moment of awakening". "I came out as a Muslim. I said: 'I'm a Muslim. My mother's Muslim. My family's Muslim. The white liberals I worked with were shocked. They'd never seen me that way. It was inconvenient for them."

"The fatwa gave prominence to the East London Mosque because they were the guys who were shouting loudest. They were the people who were protesting outside Downing Street. They had an ideology that made them relevant," he says.

This new zeal for political Islam culminated with Ed's father delivering an ultimatum - if Ed was going to live under his roof he had to give up Islamist politics. It was a stark choice between what Ed viewed as the mundane worldly comfort of his parent's home or the divine cause of serving the global Muslim community. Ed chose the latter. He ran away from home.

Ed Husain at the Edinburgh Book Festival in 2007

The adventure was short-lived as his father wanted him back under his roof, but in the following years Ed continued down the path of radicalisation.

"I moved to even more extremist organizations like Hizb ut-Tahrir who believed in a global caliphate," he says.

Ed's religious identity was shaped by notions of global injustice and suffering rather than spirituality.

"The parks in which we'd protested against Salman Rushdie were now being used to protest against UK foreign policy. We'd gone from opposing an author to opposing the British government. We'd been completely politicised."

While at college, Ed witnessed a deadly attack on a young boy who was believed to be Christian. He says it was the result of a "Muslim supremacist mindset".

The Satanic Verses

A demonstration in Paris

Salman Rushdie's surrealist, post-modern novel sparks outrage, demonstrations and calls for a ban as soon as it is published in 1988 - but also counter-demonstrations protesting against censorship and book-burning

The fatwa takes things to an entirely new level, sparking a global diplomatic crisis

Fifty-nine people die across the world - the figure includes translators who were murdered, and people who died during demonstrations

Rushdie himself goes into hiding for nine years.

"The person who killed him had come on to campus and said, 'If you have any problem with kuffar (non-Muslims) call me.' A few weeks later I saw this kid stabbed, wounded lying on the street, convulsing."

It was a wake-up call. Ed realised he'd lost sight of everything he'd loved about his faith. He distanced himself from Hizb ut-Tahrir. Later he became an adviser to Tony Blair, and one of the founding members of the anti-extremist think tank, Quilliam.

Follow Mobeen Azhar on Twitter, external

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.