Yasin Abu Bakr: Leader of Western world's only Islamist coup

- Published

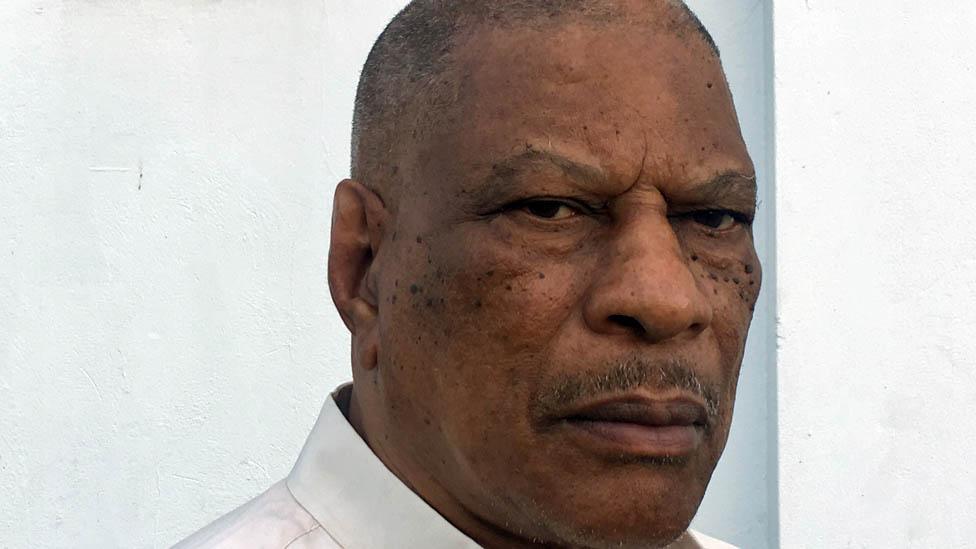

Depending on who you ask in Trinidad, Yasin Abu Bakr is either a respected religious leader, a tireless community worker, or something more akin to a Mafia godfather. Waiting for an audience with him at his mosque in Trinidad's capital, Port of Spain, Colin Freeman starts to wonder if he might be a bit of all three.

It's just after prayers on a Friday lunchtime, and, as ever, there's a queue of folk who've come to seek his help.

Many of them want counsel on spiritual matters or marriage guidance. Sometimes, though, he gets asked for help in retrieving a stolen car, settling a debt, or resolving feuds between gang members in Trinidad's crime-ridden slums.

"Alternative dispute resolution," he tells me.

Whoever he is, Abu Bakr doesn't do things by halves. A former policeman, he became one of Trinidad's first Muslim converts back in 1969, when an Egyptian preacher visited the island. Abu Bakr found Islam more attractive than Christianity, a religion he always associated with his country's past as a slave colony. He wasn't content, though, just to sit reading the Koran.

From the 1970s onwards, he spent years in Libya as a guest of Col Gaddafi, who back then was encouraging Muslim activists worldwide. He then returned home, and built up his own organisation, Jamaat-al-Muslimeen, or Party of Muslims.

In Trinidad's ghettos, it gained a following for cleaning the streets of drug dealers. Some of his converts were tough ex-cons themselves, and in neighbourhoods where police feared to tread, his "generals", as he describes them, commanded respect.

The Trinidadian government, however, did not like the idea of a parallel authority, and after a series of run-ins, Abu Bakr feared they were planning to crush the Jamaat altogether. His response, extraordinarily, was to try to crush them first.

Yasin Abu Bakr at the time of the coup, in 1990

In 1990, 100 of his armed followers stormed parliament, taking the prime minister hostage and declaring the overthrow of the government. It was the only Islamist coup ever attempted in the Western hemisphere. He surrendered six days later after being offered amnesty, and spent two years in jail.

Since then he's been committed to peaceful politics, he says. Members of his organisation, though, have been accused of Mafia-like activities - and Abu Bakr himself has been charged with, but then acquitted of, murder and extortion. More recently, there's been concern about the 100-odd Trinidadians who've gone to join Isis in Syria - a lot for a nation of just 1.3 million people.

Abu Bakr, who's polite and chatty in interviews, admits that the Jamaat has attracted the odd bad apple over the years. That's an occupational hazard of trying to reach out to wayward souls in tough neighbourhoods, he says. But he insists he'd never encourage anyone to join Isis.

"We told all our followers not to go, the whole Isis thing is utter nonsense," he tells me.

Find out more

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service - or on Radio 4 on Saturdays at 11:30 BST and on Thursdays at 11:00 BST

What Abu Bakr is more concerned about isn't the war in Syria, but the battles on the streets of Trinidad. Last year, the country saw 500 murders - more than four times as many as 20 years ago. Most are related to gang feuds in the slums, from where the Jamaat draws many of its followers.

"Generally, the gangs still respect us," says Abu Bakr. "But these days, if we tried to police them directly, the state would come down on us like a ton of bricks. So instead we have two to three murders daily - things are getting really bad now. We can't just sit and let it happen."

He won't, it seems, be attempting another coup. But the Jamaat's diagnosis of Trinidad's problems could be that of any socially conservative Trinidadian. They don't just blame poverty. They blame family breakdown, indiscipline and criminal lifestyles promoted by violent gangsta rap.

"People need proper heroes rather than rap artists or misguided musicians," says David "Buffy" Maillard, another Jamaat member. "Some music tracks can lead people into killing as much as any gun."

Maillard is well-qualified to comment. A former criminal himself, he once worked for a Jamaican gang involved in the cocaine trade in Miami. Not merely selling the stuff, but robbing other dealers. It was, to put it mildly, a high-risk occupation, which saw him shot three times, stabbed five times and serve several stints in prison.

Now reformed, he warns today that gangsterism is a much bigger threat to Trinidad than Isis. "The gangster ideology is entrenched here," he says. "You can never match the income people get from drug dealing, so you have to give them self-esteem instead. My choice was Islam. But there're other options too."

Are there though?

In Sea Lots, a slum that now claims to be shedding its gang-ridden past, one community leader told me it was still hard for youngsters to get jobs because of the area's old reputation.

As long as that's the case, I suspect Trinidad's crime problems will remain. And yes, there'll still be folk queuing to see Abu Bakr every Friday.

You may also be interested in:

At first glance it's paradise, a small Caribbean island with palm trees swaying in the breeze, white sands and emerald waters, untouched by mass tourism. But Old Providence has a guilty secret - the huge number of people who have turned to drug-running, and then disappeared.

Read: The island where men are disappearing

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.