The preachers getting rich from poor Americans

- Published

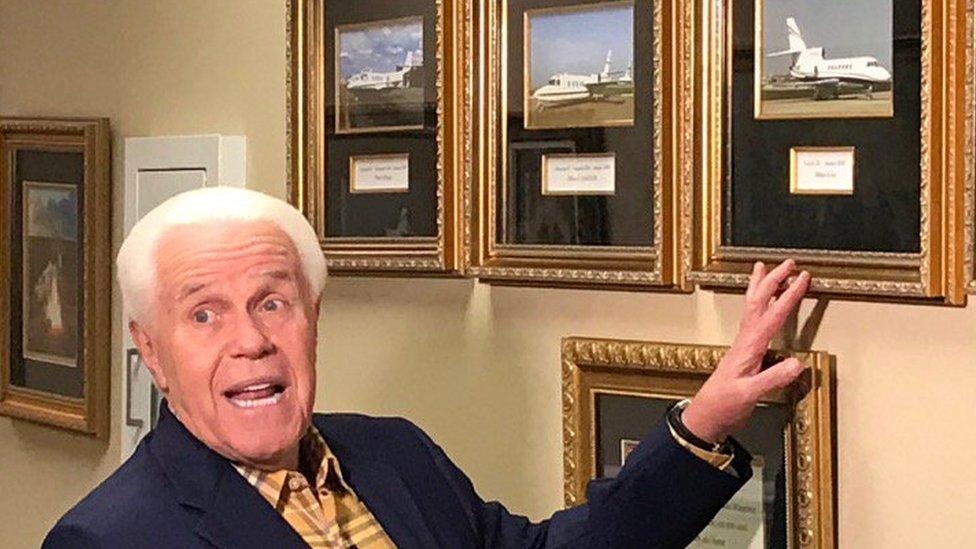

Larry and Darcy Fardette donated to many televangelists

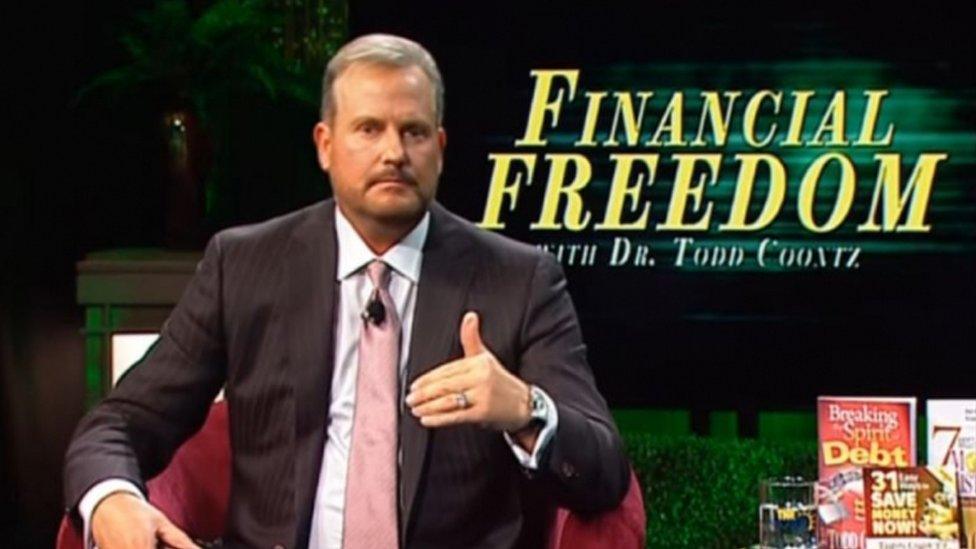

Televangelist Todd Coontz has a well-worn routine: he dresses in a suit, pulls out a Bible and urges viewers to pledge a very specific amount of money. "Don't delay, don't delay," he urges, calmly but emphatically.

It sounds simple, absurdly so, but Coontz knows his audience extremely well. He broadcasts on Christian cable channels, often late into the night, drawing in viewers who lack financial literacy and are desperate for change.

"I understand the laws that govern insurance, stocks and bonds and all that is involved with Wall Street," he once said, looking directly into the camera. "God has called me… as a financial deliverer."

Crucially, he always refers to the money as a "seed" - a $273 seed, a $333 seed, a "turnaround" seed, depending on the broadcast. If viewers "plant" one, the amount will come back to them, multiplied, he says. It is an investment in their faith and their future.

In 2011, one of those desperate viewers was Larry Fardette, then based in California. Larry watched a lot of similar televangelists, known as prosperity preachers, who explicitly link wealth and religion. But he found Coontz particularly compelling. He assured quick returns. He seemed like a results man.

And Larry needed some fast results.

The Fardette family was going through a tough time. Larry's daughter was seriously ill and he had health problems of his own. His construction business was struggling, and to make matters worse both his van and his car broke down irreparably within the same week. When a local junkyard offered him $600 for the van, he thumbed the bills thoughtfully and remembered Coontz's rousing speech.

Maybe he should invest the sum as a "seed"?

He instantly recalled the specific number that Coontz had repeated again and again: $273. It was a figure the preacher often used. "God gave me the single greatest miracle of my lifetime in one day, and the numbers two, seven and three were involved," he once said. It is also - perhaps not coincidentally - the number of Coontz's $1.38m condo in South Carolina, paid for by his church, Rockwealth, according to local TV channel WSOC-TV.

Larry has now come to realise there was no foundation to Coontz's promises that donated cash would multiply, but at the time the stirring speeches gave him hope. He did not see any other way out.

He sent off two cheques: one for $273 and another for $333, as requested. Then he waited for his miracle.

Todd Coontz claims to be a financial expert

Televangelists are not as talked about today as they were in the 1980s and 1990s, when many rose to fame and fortune through mushrooming cable channels.

But they have never gone away. Even after numerous press exposés, the rogue elements have often bounced back. Some have got even richer. Many have taken their appeals on to social media.

A number of those making the most persistent pleas for money tap into something called the prosperity gospel, which hinges on a belief that your health and wealth are controlled by God, and God is willing you to be prosperous. Believers are encouraged to show their faith through payments, which they understand will be repaid - many times over - either in the form of wealth or healing.

For followers, it is a way to make sense of sickness and poverty. It can feel empowering and inspiring amid despair. The hard-up donors are often not oblivious to the preachers' personal wealth - though they may not know the extent of it - but they take the riches as a sign of a direct connection with God. If seed payments have worked for them, maybe they can work for you too?

And if the seeds never flourish? Some are told their faith is not strong enough, or they have hidden sin. In Larry's case, he often interpreted small pieces of good fortune - a gift of groceries from a neighbour, or the promise of a few extra hours of work for his wife, Darcy - as evidence of fruition.

He estimates he gave about $20,000 to these operators over the years. A little here, a little there. A few years ago, he started tallying it all up. The list is like a who's who of all the established players, including those who have made headlines for their lavish lifestyles - those such as Kenneth Copeland and Creflo Dollar, who have asked followers to fund their private jets.

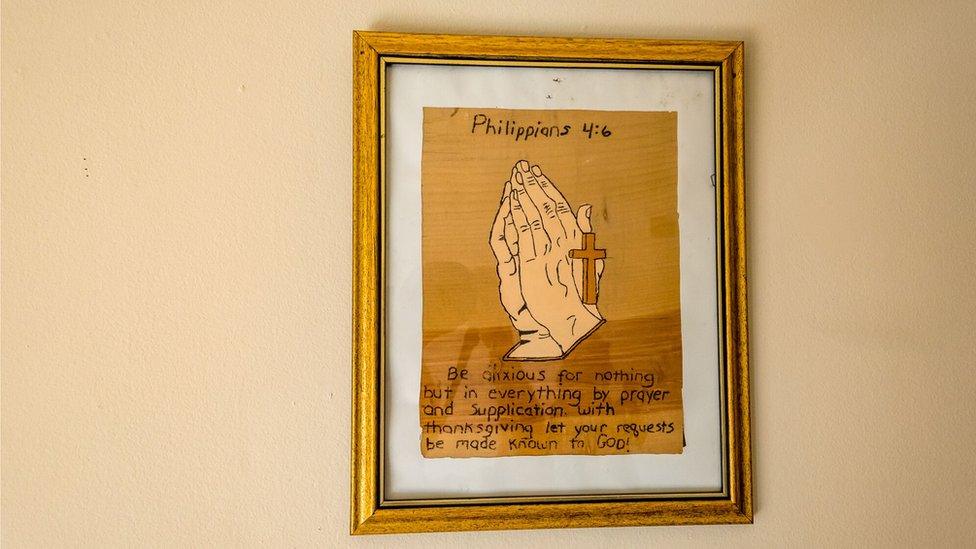

Larry's own life could not stand in greater contrast. These days he and Darcy live in the small town of Cullman, Alabama, about an hour's drive north of Birmingham. Their spartan living room is furnished with just a desk and four dining-room chairs. The monotony of the wall's bare magnolia paint is broken only by a couple of mounted crosses and a small, framed Biblical verse. "Be anxious for nothing," it reads (Philippians 4:6).

"Life is not easy but we are blessed," says Larry, in a rasping, lived-in voice. "We have food in the refrigerator, we have two cats that love us. My wife's got part-time work in a store and I get disability benefits."

Larry's painting and remodelling business fell apart when scoliosis started twisting his spine about eight years ago - roughly the same time he scrapped his van and car and made his donation to Todd Coontz. He and Darcy still lived then in his home state, California, and employed former drug users as workers. He was an ex-addict himself, and his Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous sessions had strengthened his religious beliefs.

After deciding to "follow Christ's path", he became an avid viewer of religious channels and specifically "praisathons" - fundraising events with multiple guest speakers. He became, in his words, "hypnotised" by the hosts. He was not just a passive spectator, he felt like he knew them.

Many of these pastors also ran prayer lines - where callers would speak one-on-one with an operator and they would pray together. If a request for money followed, Larry was happy to contribute - even if he did not have much to give. He was under the impression that the money was going to worthy projects at home and abroad, and he hoped that if he were ever in a desperate position, he would be helped too.

In 2013, that moment came.

His daughter's health, which had long been poor, had become critical. Larry had promised to help her financially, but his "seeds" had not flourished. He wrote a heart-wrenching, five-page letter to several ministries he had contributed to over the years, pleading for help.

"We had been faithful to these ministries. They called us partners, friends, family," he explains today. "We thought they'd be there for us."

In the letter, he detailed how his daughter's health insurance would not cover the extensive and costly treatment she needed. One doctor had suggested they waited for her organs to fail, as only then would he be able to intervene.

"As a father, I am presently helpless," he wrote. "Would you please consider sponsorship to save our daughter's life?"

The replies drifted in. Some were instant email responses, others came through the post after prompting. All were rejections. "They said things like, 'Our ministry mandate prevents us from helping you,'" he recalls. He remembers the reaction of one specific office manager, from a ministry that had publicised its funding of medical treatments in the US: "In a haughty voice, she took a deep breath and said: 'You know we get six or seven of these calls a week and if we help you, we are going to have to help everyone.'"

By summer 2014, Larry and Darcy had exhausted all their funds. They had sold all their belongings to travel from California to Florida to be with their daughter, and ended up homeless. Wracked with guilt for having failed to provide the promised help to his daughter, Larry couldn't understand why he had been let down.

It took another year for things to become clear. In August 2015, the couple were channel-hopping in a Jacksonville motel room, when they caught an episode of John Oliver's satirical news show, Last Week Tonight.

"I never watched John Oliver. I had never even heard of the guy," says Larry. But his attention was immediately caught by a skit that ripped into money-grabbing televangelists. Larry and Darcy sat up in shock, recognising all the names.

They say they felt as though God was lifting a veil. "We had been so ignorant," Larry says, shaking his head.

The next morning they went to a local library to find out more online. In just a few clicks, they came across the Texas-based Trinity Foundation, which had assisted Last Week Tonight with its research.

Larry called the phone number, slightly apprehensively, not sure whether a friendly voice would pick up.

The man on the other end listened patiently as Larry reeled off the names of the preachers he had come to know.

He told him they knew every single one of them. Not only that, they kept files on most of them, detailing what was known of their estimated fortunes.

Stunned, Larry stayed on the line talking through his experiences, relieved to find someone who understood.

In its early days, in the 1970s, the Trinity Foundation was a wild place.

It was a home church but far from the twee set-up you might imagine. Here Bible classes were so fiery they could end in fist fights.

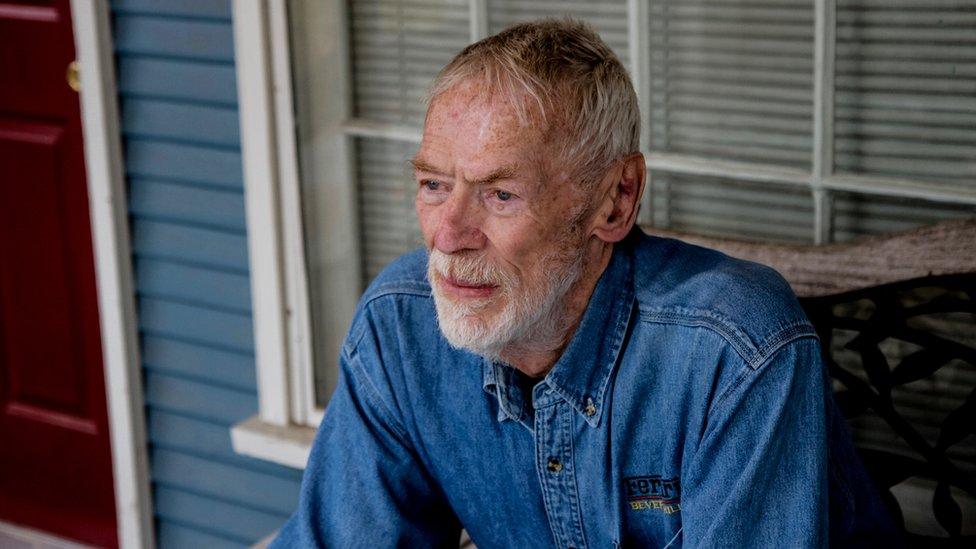

The dominant figure was the foundation's extraordinary creator, Ole Anthony (pronounced Oh-lee). At 6ft 4in, with penetrating blue eyes, he was a former teenage delinquent who had dabbled in arson and taken heroin - and had gone on to become an Air Force intelligence officer, a failed Republican election candidate and the owner of a PR firm, all before the age of 33. Then he underwent a sudden religious conversion, renounced wealth and devoted his life to Christ.

A friend, John Bloom, later wrote that Ole had assumed old business colleagues would join his Bible study groups. "But Ole was a little too 'out there' for most three-piece-suit North Dallas Protestants," Bloom explained. He was also based in a "fleabag office" in a rough part of town. Consequently, he mostly attracted troubled characters with nowhere else to go.

Ole Anthony on his front porch in Dallas

It was during these sessions that Ole started to note a common thread. When people were on the verge of homelessness in the heart of the Bible belt, a surprising number offered the last of their cash to televangelists who promised them financial salvation.

Ole, who always had a have-a-go approach to problem-solving, felt an urge to step in. First, he tried approaching the ministries on behalf of the penniless donors, thinking he could explain the circumstances and get the money refunded. However, like Larry, he found no-one willing to talk.

So he took it to a Christian broadcasting association - but it didn't want to get involved. Then he approached local district attorneys, who explained that many preachers were protected by the First Amendment (guaranteeing freedom of religion and free speech), so there was nothing they could do. So he turned back to the media, this time major networks and publications, which said investigations would be too time-consuming.

Ole was faced with a multibillion-dollar industry built, as he saw it, on exploiting the poor - and it was completely untouchable.

And this is how a community church became an investigations office. The Trinity Foundation felt compelled to tackle the prosperity preachers because no-one else would.

It is hard to imagine brawls at the foundation these days. Most of its members are at retirement age - Ole himself is 80, and in failing health - and the operation has moved from its "fleabag" office to two adjacent houses in a sleepy part of east Dallas. On one side is the gentrifying Junius Heights neighbourhood, on the other rows of slightly run-down bungalows.

Every day there is an early-morning Bible study session, a group dinner at 5pm, and more theology in the evening, including prayers with guitar-led hymns. The mixed bunch of devotees now includes a Mexican economist and a veteran of Desert Storm.

"Our members have taken over a whole block," says Ole incredulously, as he smokes a pipe on the front porch. Their semi-communal way of living has led to allegations that they are a cult, but he dismisses this as nonsense. "A lot of people don't like me, you know," he says, more than once.

Ole's dogged work has steered the foundation into an unusual niche, forming a bridge between the Christian world and the media. Though journalists originally pushed him away, they later found his foundation could provide the springboard for their investigations. Gradually it morphed into a watchdog, maintaining detailed files on wealthy evangelists.

"We have done a lot of weird things," Ole concedes, between hacking coughs.

Over the years, they have gained a reputation for their gung-ho approach - diving into dumpsters outside ministry offices, in search of potentially incriminating paperwork, and going undercover.

Collaborating with ABC News in the early 1990s, Ole posed as a small-scale pastor trying to learn how big-money ministries work. Accompanied by a producer with hidden cameras, he went to a mailing company working for televangelist Robert Tilton and was told how posting gimmicky gifts to potential donors had boosted returns.

It was a well-known technique - sending things such as "vial of holy water" or even dollar bills to prompt people to send a financial gift back - but it was rare to hear someone admitting it.

When the TV reports aired on Diane Sawyer's Primetime Live show in 1991, Tilton denied wrongdoing and attempted to sue the network - but he failed and his TV shows were eventually cancelled.

(Today, the Tilton ministry is still active but on a much smaller scale.)

A couple of years later, the Federal Communications Commission reportedly came close to introducing a "truth-in-advertising" clause for religious solicitations. This would have meant that any claims of boosting finances or curing disease would have to be verifiable, and Ole took various trips to Washington to lobby for it.

Ultimately the idea was dropped, which Ole puts down to the fact that the Republicans won the House of Representatives in 1994, with the help of votes from the religious right.

"We've tried a lot of things, but we haven't been very successful," he says, ruefully.

He doesn't think much will ever change, but asked if this makes him frustrated or angry, he laughs. "Why would I make myself angry? That is all there is in this world, injustice."

The Trinity Foundation office - also a home for some members

Pete Evans - a bespectacled believer with a gentle, apologetic manner - is now the foundation's lead investigator. One of his specialities is tracking the movements of private jets, aiming to discover when pastors are using them recreationally, instead of for church business.

Pete took Larry's first phone call. He remembers being moved by it, and starting a crowdfunding page for him. It raised about $2,000. "Less than what we had hoped for, but enough to tide them over," he wrote on the website at the time.

Pete says that just over a decade ago there was great excitement within the foundation, when the US Senate's Finance Committee began to question whether evangelists were taking advantage of their tax-exempt status to break Internal Revenue Service (IRS) guidelines.

While other tax-exempt organisations - notably charities - must at least fill in a basic form, known as the 990, churches don't have to. This means they are not required to detail their top employees' earnings or list how much is spent on philanthropic projects. Their inner workings can be entirely unknown.

Pete Evans joined the Trinity Foundation as a student in the 1970s

But in 2007 the Senate committee appeared to think that some ministries were abusing this privilege and violating an IRS rule that church earnings may not "unreasonably benefit" an individual.

The Trinity Foundation shared all its research with the committee, and attended meetings with its officials.

The group - led by Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley - decided to focus on six well-known figures: Joyce Meyer, Creflo Dollar, Eddie Long, Kenneth Copeland, Benny Hinn and Paula White - who is now President Trump's spiritual adviser.

All six denied wrongdoing. Four failed to co-operate satisfactorily, according to the committee (White, Copeland, Dollar and Long). Larry had donated to three of them.

"We really thought it was going to come to something," says Pete.

Yet by 2011, the investigation had lost steam. Senator Grassley drew no specific conclusions. Instead he asked an evangelical group - the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability (ECFA) - to study ways to spur "self-reform" among ministries.

"The whole thing frittered away," says Pete. He believes the 2008 economic crash played a part; the financial world suddenly had much bigger issues to deal with. "But we were extremely disappointed. After years of hanging on, it felt like they just punted the ball."

The ECFA refused a BBC request for an interview, but said it stood by past statements on its website. In 2009, it told Senator Grassley that filing full tax returns would be an "intrusion on the most intimate recesses of church administration".

The Senate committee has shown no sign of taking up the subject again, and no government agency has taken a strong interest in it.

Paid-for television channels also fall outside the remit of the national regulator, the Federal Communications Commission - unlike in the UK, where Ofcom might step in.

Meanwhile, an anonymous source at the IRS told the BBC that the service feels its hands are often tied. "We can't knock on doors because then it is 'government overreach'," he said. "And if you think someone is going to thank you for closing down their church..."

But, although it is rare, sometimes a pastor does come within the IRS's sights.

In 2013, one of Todd Coontz's neighbours called a local TV channel to complain that he was taking up too many spaces in the car park outside his luxury South Carolina apartment block.

"He was not a known name around here," says Kim Holt, who runs the investigations unit at WSOC-TV in Charlotte, North Carolina. "But the caller then started mentioning Coontz's church and the 'seed' giving. And that's when we got interested."

The channel got in touch with the Trinity Foundation, which provided background on Coontz and the prosperity gospel. The foundation also shared recordings of his TV appearances - it keeps an archive of televangelist broadcasts, taking notes on the programmes to monitor new techniques.

"There is a peculiar thing about people turning the TV on in the middle of the night," says Pete, adding that this is when many pastors broadcast their pleas for seed donations. "They are lonely or hurting. They might have medical condition or be unemployed."

When WSOC-TV's report on Coontz aired, it went far beyond the parking dispute, detailing his personal wealth and casting doubt on the legitimacy of his fundraising tactics.

Todd Coontz on his way to the courtroom

Todd Coontz is not in the same league as some of the other prosperity preachers. He does not have a megachurch, a private airfield or even his own jet. He preaches at other people's live events, rather than holding them under his own name.

But his lifestyle is certainly opulent. He has posted photos on Facebook of his stays in hotel rooms overlooking Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills. He has spent tens of thousands on jewellery and diamonds. He also has, or at least had, a fleet of luxury cars, including three BMWs, two Ferraris, a Maserati and a Land Rover, plus a speed boat.

Meanwhile, he has continued to target his operations at those on the breadline. Under the title Dr Todd Coontz, he has written a series of books: Please Don't Repo My Car, Supernatural Debt Calculation, There Is Life After Debt.

In the same year as the TV report aired, a federal probe led by the IRS criminal investigation unit also began.

"That certainly does not seem like a coincidence," says Pete. "I think someone saw the report and thought, 'This is crazy. We can't let this go.' It was such a public display of the misuse of donor money."

The IRS did not delve into his "seed" operations or his tax-exempt church, Rockwealth, but into his taxes for various personal side projects.

He was making large profits from freelancing as a speaker for other ministries and his two for-profit businesses, selling his books, CDs and DVDs. For these, he had needed to file accurate tax returns.

Todd Coontz's website still encourages "seed" donations

During a four-year investigation, prosecutors dug up all sorts of irregularities, ruling that Coontz had been underreporting his income and exploiting expenses claims.

He had developed various ploys, such as flying economy but sending fake first-class invoices to the ministries he was freelancing for, so he could pocket the difference. He would also claim expenses twice, once from his own ministry and once from his client. He claimed for thousands of dollars spent on clothes (suits are not a permitted business expense) and for 400 cinema tickets, which the IRS also considered unreasonable.

On 26 January 2019, Coontz was sentenced to five years in prison for failing to pay taxes and assisting in the filing of false tax returns. He was also ordered to pay $755,669 in restitution.

He reported to jail in early April, but was freed by the judges, pending appeal.

Coontz did not respond to the BBC's request for comment, but he has previously denied wrongdoing. On his website, he also claims to have given more than $1m to charity.

His Twitter account is still posting daily (with no reference to his jail sentence) and he has taken to preaching - via the Periscope app - from the front seat of his Maserati.

"Are you calling to sow your $219 seed today?" was the immediate response when the BBC called Rockwealth's hotline. The operator was not able to share the significance of that figure and would not answer questions about how many people had called to pledge. "Not so many today, but there are several of us answering calls," she said. It is not clear whether the switchboard was serving only Rockwealth or other churches too.

The Trinity Foundation has recently filed a long report to the IRS, calling for Rockwealth to lose its status as a tax-exempt church. As always, it feels like a shot in the dark and it does not expect to hear back.

Both Ole and Pete says the work they do often falls flat - and not through a lack of effort at their end. They once helped a woman get her $1,000 donation back from a ministry, only for her to donate it all over again. "She called us afterwards, asking to get it back again," recalls Pete, saying they had to decline the second time. "My feeling is she was addicted. She just got hooked back on to the TV and believing what they said."

Ole remains disappointed that the authorities still allow the vulnerable to fall into these traps.

"We hoped for change," says Ole. "But it didn't work. I guess they didn't want change."

As for Larry and Darcy, they are also still donating, despite their meagre income, but only to their local church.

Cullman, Alabama, where Larry and Darcy Fardette now live

"Plant your investment of your time, talent and money into the local community and you are going to find people who need help," says Larry, adding that he knows his neighbourhood pastor personally.

Their daughter is alive, but, after Larry was unable to pay for her medical treatment, a rift arose between them and they now rarely talk.

The couple say they want to share their story with others to make them think twice about where their money could be going.

"We found out the hard way. These are money-making industries," says Larry vehemently.

Darcy, sitting on one of the dining room chairs in the middle of the empty room, nods in agreement. "You have got to see some of the houses they live in," she adds, pursing her lips together. "Must be nice."

.

- Published30 May 2018