Yaba: The cheap synthetic drug convulsing a nation

- Published

Hundreds of thousands of people in Bangladesh have become hooked on yaba - a mixture of methamphetamine and caffeine sold as cheap red or pink pills. The official response has been harsh, with hundreds of people killed in alleged incidents of "crossfire".

"I was awake for seven, eight, even 10 days at a time. I was taking yaba in the morning, the afternoon, in the evening, again late at night, and then working all night and not going to bed."

Mohammed was an addict. After staying awake for so long, he would crash.

"I would black out. I totally went down. After two or three days I would wake, have food, and go to bed again. But if I had any yaba, I would take it - if you have a single pill left, you will take it."

Mohammed's yaba habit started at work in Dhaka.

"Our import business was with Japan so we had to work at night because of the time difference. One of my colleagues told me about yaba. He said that if I take it, it will help me stay awake, be more energetic and to work hard in the morning and late at night."

At first, Mohammed experienced the benefits his colleague described. But they were short-lived. Mohammed began behaving erratically, and came close to breakdown.

"In the early stages of using yaba it has a lot of positive effects. Everything is enhanced with yaba," says Dr Ashique Selim, a consultant psychiatrist specialising in addiction.

"You become more sociable… You enjoy music, cigarettes and sex more. In Bangladesh there's a very unhealthy association between yaba and sex - you're awake longer, you've got more energy, you feel more confident. If you stop using yaba, there are no withdrawal symptoms, it's not like alcohol or heroin. But it's the effects of yaba that are really addictive. It's a very, very dangerous drug."

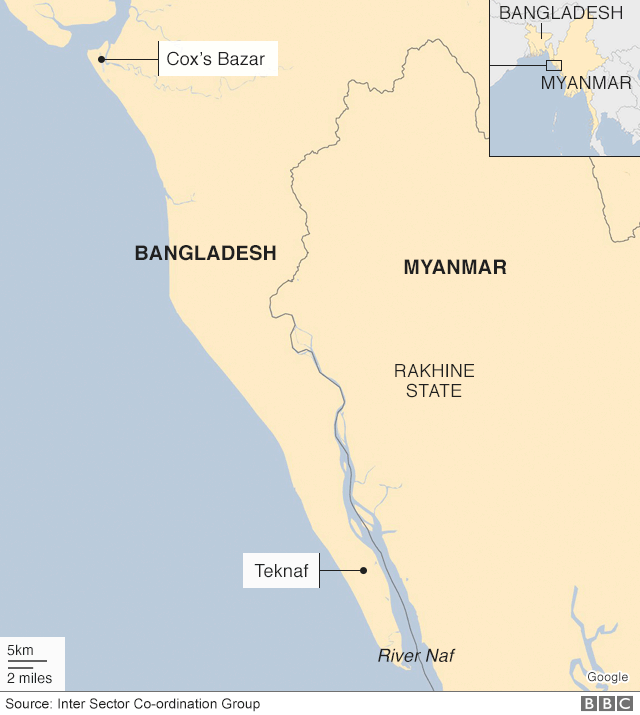

Yaba first appeared in Bangladesh in 2002 and its use, and abuse, has steadily risen since then. Manufactured illicitly in industrial quantities in Myanmar, it is smuggled into Bangladesh in the far south-east of the country, where the border partly follows the River Naf.

It was across this river that hundreds of thousands of desperate Rohingya refugees fled into Bangladesh in 2017, to escape from the Burmese military. Now nearly a million destitute refugees live in makeshift camps in the region and dealers have succeeded in turning some of them into mules - often women, who smuggle packages of pills inside their vaginas.

Experts believe the dealers see an unmissable business opportunity. At a time of rapid growth - Bangladesh has one of the world's fastest growing economies - traffickers are dumping huge quantities of yaba, and selling it cheaply to create a captive market. Anecdotally, it seems its use is becoming more prevalent among go-getters riding the economic boom.

"I was totally dependent on it," remembers Mohammed.

His wife, Nusrat, who was caring for a new-born baby at the time, says his behaviour became more and more unpredictable.

Mohammed and his wife

"He used to come home and blame me for everything regarding food, friends, my job… This was very unusual, and it's not actually like him," she recalls.

After she found some yaba tablets in the house, she tackled Mohammed about them.

"He screamed at me. I tried to convince him to get some treatment, but he was still denying it. He said, 'You don't trust me, you want to go away with someone else, you want to be apart from me.' I had a tough time. And at the same time I knew he could do anything - he could even kill us."

According to Dhaka psychiatrist Ashique Selim, yaba has filled a unique role in Bangladesh, a nation where alcohol is not freely available, and drinking is often frowned upon.

"I had a gentleman who came to me who'd led a pretty straight life. His parents were very conservative. So when his friends would go out and have a few beers, he wouldn't do that because he didn't want to come home smelling of drink. Then in his 30s he came across yaba. So there were no visual changes in the way he looked, and there was no smell. And when he was having small doses there was no effect the day after."

Officers stop rickshaws near Cox's Bazar

But yaba users struggle to keep their habit purely recreational. And it is the drug's widespread availability, and the chaos it is causing, that provoked the Bangladeshi government to ratchet up the penalties for yaba possession, and to declare "zero tolerance" - a policy that some claim involves summary execution by law enforcement agencies.

"I was coming back from the mosque, when I saw a lot of policemen in front of my gate," remembers Abdur Rahman, who lives in Teknaf, the town at the heart of the yaba trade in the south-eastern district of Cox's Bazar.

"They entered my house, and found my son, Abul Kalam in the bathroom. They grabbed him and handcuffed him. I said, 'Please release him, what has he done?' The policeman told me, 'If you talk too much, we're going to shoot you.'"

Abul Kalam had recently served a prison sentence for human trafficking, not drugs. He was held in the police station for five days before his father got some very bad news.

Abdur Rahman

"The police told me my son was killed in a gunfight," he says.

Abul Kalam died on 9 January some distance from the police station in what the police said was an incident of crossfire. The media reported another man was killed alongside him, and that 20,000 yaba tablets and five guns were recovered from the scene.

One human rights organisation estimates that in 2018, in the first seven months of the government's anti-drug operations, nearly 300 people were killed across Bangladesh. The local press often puts the word "crossfire" in inverted commas, reflecting a widespread suspicion that sometimes these shoot-outs are staged.

Find out more

Listen to Bangladesh v Yaba on Crossing Continents, on BBC Radio 4, at 11:00 on Thursday 25 April

But the Superintendent of Police for Cox's Bazar, A B M Masud Hossain, denies there is a shoot-to-kill policy for those suspected of involvement in the yaba trade.

So how does he explain the circumstances of Abul Kalam's death?

"Sometimes when we go for an operation, we face the yaba traders. I think that was such a type of incident," he says.

"After arresting someone we take them to the police station. Then, after collecting information during interrogation, we go for the operation. So when you take the criminals on the operation, sometimes they fight the police with guns. So maybe he was killed at that time."

Police superintendent A B M Masud Hossain: "I can assure you, there is no crossfire list"

And he has an explanation, too, for the fact that these deaths always seem to follow a similar pattern.

"They may be the same stories, but the incidents always occur like this. So why would I give another story?"

In February, the superintendent organised an extraordinary public event in Teknaf. In a carnival atmosphere, in front of a crowd of thousands, 102 local men - all alleged yaba dealers - surrendered to the authorities. They included relatives of the former local MP for the ruling Awami League, and of other elected representatives. Thirty firearms and packets containing 350,000 yaba tablets were laid out ceremoniously. The men who had given themselves up lined up in front of a podium decked with flowers, and each of them was presented with a single gladiolus flower by the Home Minister, Assaduzaman Khan.

"The entire country is flooded with yaba, even students in schools and colleges are dependent on it," the minister told the assembled crowd.

Carnival atmosphere: 102 men surrender themselves in Teknaf

Then he addressed the men who had turned themselves in, and who remain incarcerated today.

"Your very presence today is reassurance for all of us that we shall be able to eradicate yaba from Teknaf and the rest of the country."

It sounded as though those alleged yaba traders came forward of their own volition. But one man claims that his brother, Shawkat Alam, surrendered because he feared for his life.

"The police made a list of all the people who had to be 'crossfired', something like that," says Mohamed Alamgir. "And when my brother heard about it, he was so frightened that made him surrender."

Police superintendent A B M Masud Hossain rejects the allegation that pressure was applied.

"I can assure you, there is no crossfire list. We always try to arrest them."

And he says, since February's surrender, yaba trading in the district of Cox's Bazar has decreased by almost 70%.

A border guard finds yaba in a bus near Teknaf

In 2018, Bangladeshi authorities seized 53 million yaba tablets nationally. The total value of this illicit business is estimated to be worth upwards of $1bn a year.

There are no reliable surveys of the number of drug-dependent people in Bangladesh. The Department of Narcotics Control (DNC) estimates there are four million addicts, but NGOs have put the number at nearer seven million. Of those, about a third are thought to be yaba users.

Mohammed's yaba highs were quickly replaced by wretched lows.

"I was always confused and felt that somebody was overhearing me, somebody was looking at me."

Paranoia is not unusual among yaba users.

As his life spiralled out of control, Mohamed was forcibly taken to a rehabilitation centre in the middle of the night by strangers employed by his family. It was traumatic, but he is grateful now. He spent four months in treatment, has been clean for more than a year, and still volunteers in the same clinic - partly to prevent his own relapse.

"Now I think he's ready to get a job again," says Nusrat, Mohammed's wife. "But I never push him. And if he says he needs some help, we're all here for him."

Mohammed's addiction to yaba proved a profound test of this couple's relationship.

"But our bond has become stronger," believes Nusrat. Mohammed agrees.

"And I have more faith in her. I know she won't leave me!" he says.

You may also be interested in:

When soldiers went searching for militants in Myanmar's Rakhine state last October, the result for members of the Rohingya minority was disastrous. Villages were burned, men were killed, women were sexually abused. And when one woman complained of rape, she was accused of lying by the office of the country's leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, and hounded by vengeful soldiers.

Hounded and ridiculed for complaining of rape

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.