'We were bullied out of our home for being different'

- Published

A family with two autistic children say they were driven out of their home as a result of a two-year campaign of bullying, abuse and physical assault. The authorities failed to help them, they say, and mistook the symptoms of autism for aggression and an unwillingness to co-operate. Charlotte Hayward went to see them.

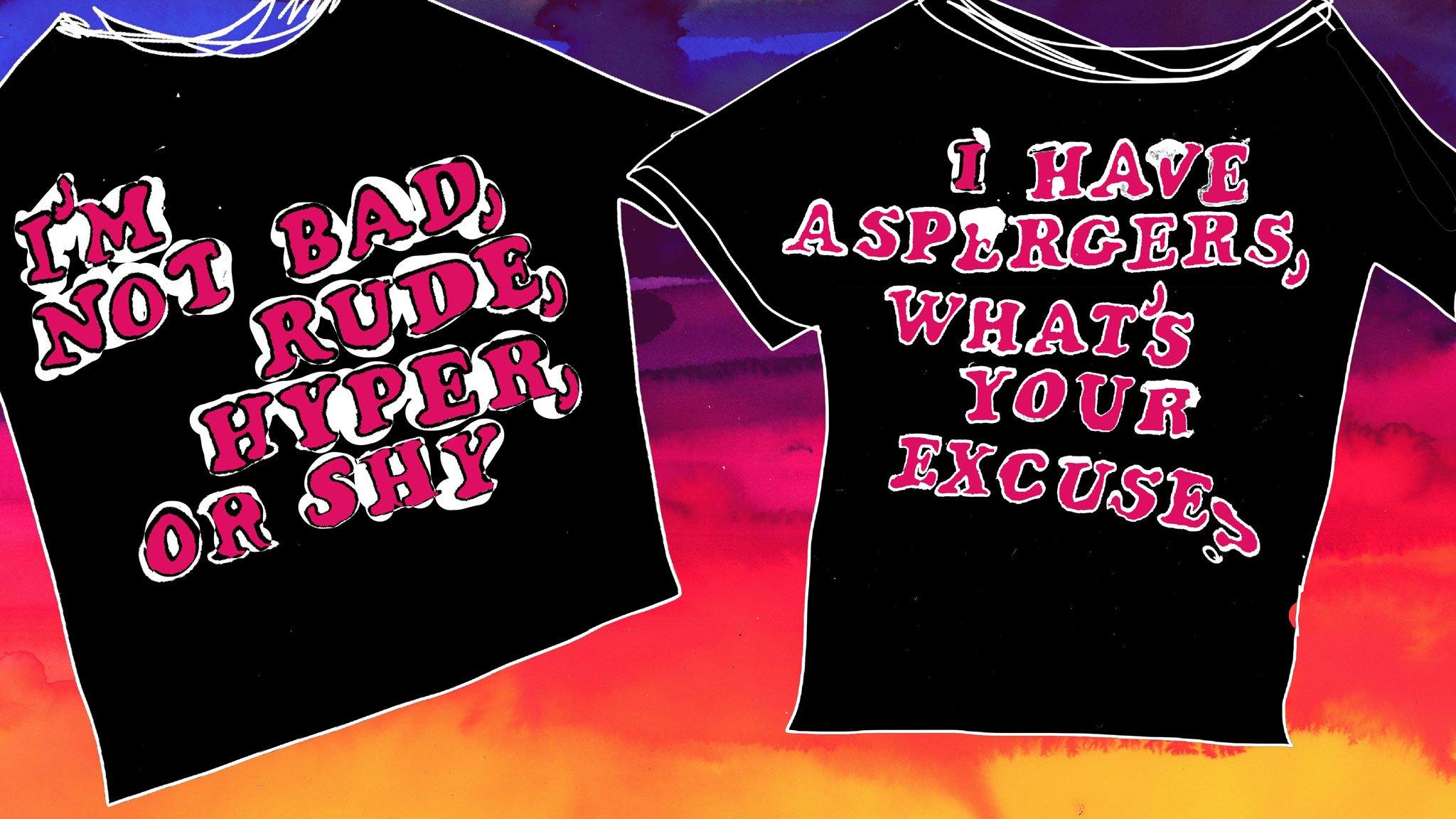

"I'm not bad, rude, hyper or shy, I have Asperger's. What's your excuse?"

Lee is reading out to me what's written in pink letters on his black T-shirt. He's also wearing yellow earplugs, sunglasses and a hat. He himself would admit that it's an unusual look, especially in grey, rainy Britain.

He says he bought a number of similar shirts because dealing with the police left him very frustrated.

"The police were so rude and judgmental and had no idea how to communicate or talk to us," he says. "They just shut us up straight away."

Lee is a father. He's got five children, two of whom, like him, have a diagnosis of autism. His wife Penny can't walk very far, and so sometimes she uses a mobility scooter or a wheelchair. They describe themselves as a "bit different".

Two-and-a-half years ago they were offered an adapted new home by the housing association, LiveWest - to protect the family's privacy the BBC is not naming where. They were happy to move but problems with neighbours began soon after they arrived.

"It started off with antisocial behaviour, and youths would come out and play football but they would come and purposely kick it at the vehicles and the windows. We started getting abuse from the parents, telling us we were odd and weird, and then we started getting blocked in," says Penny, who is currently pregnant with her sixth child.

Find out more

Listen to Charlotte Hayward's report on the Today programme, on BBC Radio 4, after 06:00 on Monday 6 May

As she talks to me in the calm of the family's cream-coloured living room, her children sit next to her, listening quietly. But it's a difficult and upsetting story to tell, and she has to keep stopping.

"Every time we left the property, we got hurls of abuse, footballs kicked in our direction, even some of the youths saying they wanted to kill us."

Bricks were thrown at them, she says, and through the windows.

"They'd shout at the girls - call them retards. They were harassing my husband doing hand flapping and mimicking his ear defenders."

Over the course of two years, Penny made hundreds of complaints to LiveWest and Avon and Somerset Police. The police say these complaints were investigated and that several family liaison officers were assigned to the family, all of whom were rejected.

The family says they rejected the officers, because none had the skills required to talk and listen to autistic people.

LiveWest, the housing association, said in a statement: "Over a long period of time, there were accusations of hate crime made by the family along with many counter-accusations by local residents. We worked with the police and multi-agencies to investigate all these accusations where no action was taken by the police due to lack of evidence."

Adding to the family's sense of being abandoned by people who could have helped them, at the height of the tensions LiveWest revealed that it had accidentally sent sensitive information to the family's neighbours by mistake. Medical information, previous addresses, schooling for the children, mental health assessments.

It was a catastrophic data breach and Penny says she was gobsmacked.

"I was… I didn't know what to say. 'What do you mean, you've sent them my whole file?'"

LiveWest says it has apologised to the family for the error.

The abuse culminated in an assault on the couple's eldest son, Harry, who has Tourette's syndrome and autism.

It was caught on the family's private CCTV, which shows a handful of people outside the family's house: Harry is leaning forward, perhaps talking, and then someone grabs him, pushes him against a wall and bends him forward over railings.

You can't hear much on the short clip, and you can't see what the build-up to this was or know the context.

"After the incident the autistic ones were having real severe meltdowns. It really affected them quite badly and of course the two youngest siblings witnessed everything. They were really distressed. We had a six-month-old baby as well. Harry particularly was punching doors and walls and cutting all his hands open, just pure frustration," says Penny.

"Three hours after the assault the police came and knocked on the door and I couldn't let them in. I couldn't distress them any more, especially Lee because he wanted to protect his family. So Lee says, 'I'm really sorry you can't come in tonight, we're trying to cope and get this family stable and secure and for an autistic person routine is everything. We said we'll speak to you tomorrow. In the meantime, we've got CCTV for you.'"

Avon and Somerset Police wasn't able to give the BBC an interview, but did say that it had been alleged that Harry had pushed someone before he was attacked. When officers asked to review all the CCTV, the family wouldn't co-operate, a spokesman said. That meant that the assault, which would have been treated as part of an affray, couldn't be investigated.

The family told me they had not kept the previous CCTV footage.

The police say they did arrange a meeting to go through all of the allegations after the assault but that Penny and Lee didn't want to take part.

Penny says she didn't feel any of the police officers had an understanding of what autism is.

"They made us appear to be unengaging, unco-operative," she says. "We eventually paid an advocate to speak for us. They said we were aggressive, abrupt. If you know anything about autism, communication is the biggest issue."

What is 'normal'?

Harry, 19, was too distressed to be interviewed, but commented by email:

Not long after we moved in, people in the street started to bully me. I started to feel very socially awkward all the time and became a person with very low self-confidence. I got to breaking point and I didn't understand all my emotions. I didn't know how to feel and felt that I didn't deserve to be on this planet where everyone judged me and mocked me.

I was subjected to violence and after this I became very depressed and now a year on I am still struggling. I don't like leaving the house. I sit in my room with the lights off and curtains closed with no interest in anything any more. I feel like a stranger in my own home, my own body. I no longer know myself.

I feel as someone with autism I am judged and overlooked because of who I am and because I am different. But what is "normal"?

Avon and Somerset Police doesn't train its officers specifically to deal with autism. It points out that College of Policing guidance doesn't support condition-specific training, because officers cannot be expected to be "health or social care professionals".

But that could be changing. Sgt Adam McCloughlin, the force lead for autism, has been working on a programme that would improve officers' autism awareness.

"We know that autistic people are up to seven times more likely to come into contact with the criminal justice system. We know that is most likely as a victim or as a witness, certainly not as a suspect," he says.

"There's nothing to suggest that autistic people are more likely to break the law. Policing is one of those occupations where you only really ever tend to meet people in times of stress, when you've done something wrong or something unfortunately has happened. Emotions play a big part in the way autism presents itself. People that the police come across will be in emotional distress."

He hopes the training will start this year.

"I think that we as an organisation make mistakes every day," he says. "I've seen the complaints from the autistic community. I think the answer to those performance issues is just more awareness and more training. We're not going to do any harm by reframing the way we think about vulnerability and other conditions."

Penny and her family felt forced to move to a new home. They tell me that they're safe but despite the police's insistence that they tried to help the family, they feel completely let down.

"You go to the police because they are mean to protect you, you go to housing association, they have a duty of care to look after you… We had no family, there was no support network, just absolutely nothing."

You may also be interested in:

Two brothers on the autistic spectrum were looking for work when one had the idea of opening a comic shop. It turned out to be an inspired choice.

Read: The shop where it's OK to be different

Illustrations by Katie Horwich