The Red Zone: A place where butch lesbians live in fear

- Published

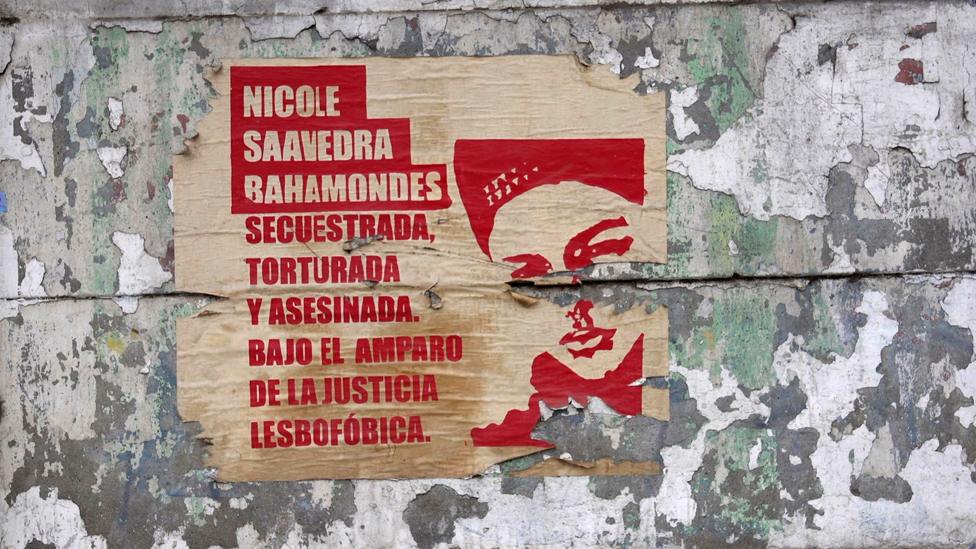

Three mysterious deaths and dozens of violent attacks on butch lesbians, or camionas, have put lesbians in Chile's Fifth region on red alert.

Nicole Saavedra Bahamondes' family knew she was not a morning person.

Especially at weekends, the 23-year-old did not leave her bedroom early - and she knew her mother wouldn't disturb her in her cosy bed, still laden with the cuddly toys from her childhood.

At about 11:00 on a Saturday, Nicole would usually emerge and walk slowly to the kitchen in search of coffee.

She would blearily exchange words with her mother, Olga Bahamondes, giving monosyllabic answers to any questions about the night before.

Around 11:30, Nicole would WhatsApp her cousin, María Bahamondes, who lived five minutes away with her husband and two young daughters. Often they would agree to meet at the farmers' market in their sleepy mining town - El Melón, in Chile's mountainous Fifth region - then go back to María's house for lunch with her two young children.

But this Saturday morning, 18 June 2016, was different.

Nicole had messaged her mother the evening before to say she would be staying overnight at a party with friends in Quillota, a town some 30 minutes by bus from their home. Then at 07:00 she sent a voice-note to say she was on her way back.

When Olga woke and listened to the voice-note she assumed Nicole was already home and resting in bed. But when she hadn't emerged by midday, Olga popped her head into her daughter's room.

It was empty, and the bed had not been slept in.

Olga called Nicole immediately, but there was no ringing tone. This was unusual. Nicole's phone was rarely off.

Olga began to worry.

Nicole's Instagram showed that she and her friends had been in high spirits just hours earlier.

She'd uploaded five videos of the group laughing, sitting on mattresses on the floor, surrounded by cushions, empty Coca-Cola bottles and cigarette lighters.

In the last 15-second Instagram video posted just after midnight, a young woman with long dark hair and her hoodie up is seen scrolling through her smartphone. The camera then pans to a man in his early 20s, who sings an off-key version of Lana Del Ray's Video Games.

Nicole, who is out of shot and filming the video, can be heard giggling.

Then there is social media silence.

María and Nicole had been especially close. Growing up, the cousins and their mothers had lived together in one house.

"Nicole and I always had a special bond. We were raised by single mothers who were sisters. We were more sisters than cousins," says María. "We saw each other every day, and after I got married and moved out, every few days."

María was protective of her younger cousin.

"I have always said that she lived in another world," says María. "Because she didn't see the bad side in people. I think that is what played against her."

María Bahamondes: A man attacked Nicole a year before her death

Nicole was vulnerable, María felt, because she openly identified as a lesbian - and not just as a lesbian, but as a camiona, Chilean slang for a butch lesbian.

Nicole was proud to be a camiona, it was the core of her identity. But this made her visible in their small, conservative community, and she had been beaten up because of it.

"She was always being insulted. She was 14 years old when she had her first girlfriend. Men sometimes chased her and said they were going to correct her, to 'make her a woman'," María says.

In 2015, a neo-Nazi gang member brutally attacked her, yelling lesbophobic abuse.

"If her friend hadn't arrived, Nicole probably would have died. He had put his boot on her neck and was beating her and beating and beating her."

After that, María felt uneasy whenever Nicole left the house alone. So that Saturday morning, when Nicole couldn't be reached, she had a deep sense of foreboding.

When there had still been no word from Nicole 24 hours later, the family notified the police and María organised relatives into search parties, to retrace Nicole's last known movements. The first point of call was the house in Quillota where Nicole had spent the night with friends.

The friends had already explained that Nicole had set off for the bus stop at 07:00 and that they had heard nothing from her after that.

On Sunday they still had no news.

"We searched and searched for her," María says.

They walked the streets of the town. They marched through the farms and avocado plantations that surround it. Nothing.

The search continued, but on Friday 24 June, almost a week after Nicole's disappearance, a sickening feeling washed over María.

"My heart told me that things were wrong," she says.

She returned to her house and kneeled.

"I prayed to God asking Him to help us find her body, because now I felt that Nicole was dead. That day I felt that Nicole wasn't coming back."

The following day, police found her body dumped by a farm track not far from Limache Reservoir, 15 minutes away from the bus stop where she was last seen.

Espino trees near the spot where Nicole's body was dumped

As we approach the spot on a hill pierced with pylons, María walks a little ahead. Occasionally she points out piles of horse manure to avoid on the brown earth.

"It's strange," she says quietly. "There used to be more shrubs around here. Someone must have cut them down."

Then she stops walking.

"Here," she says softly, nodding slightly with her head, to a patch of earth, surrounded by leafless bushes and horse manure. She looks away.

The police files say that Nicole was killed by repeated blows to the back of her head. Her body had numerous open wounds and bruising. Her hands had been tied behind her back. Her wallet, money intact, was still in the pocket of her trousers. Nicole's killer had not wanted to rob her.

María pauses.

"It was really shocking. Really shocking. We never expected this - that she would have been tortured and beaten like this. You don't think that someone you love is going to die in circumstances like that."

The police said they had no leads that might help them identify the killer. But María felt sure she knew the motive.

Nicole had her own look.

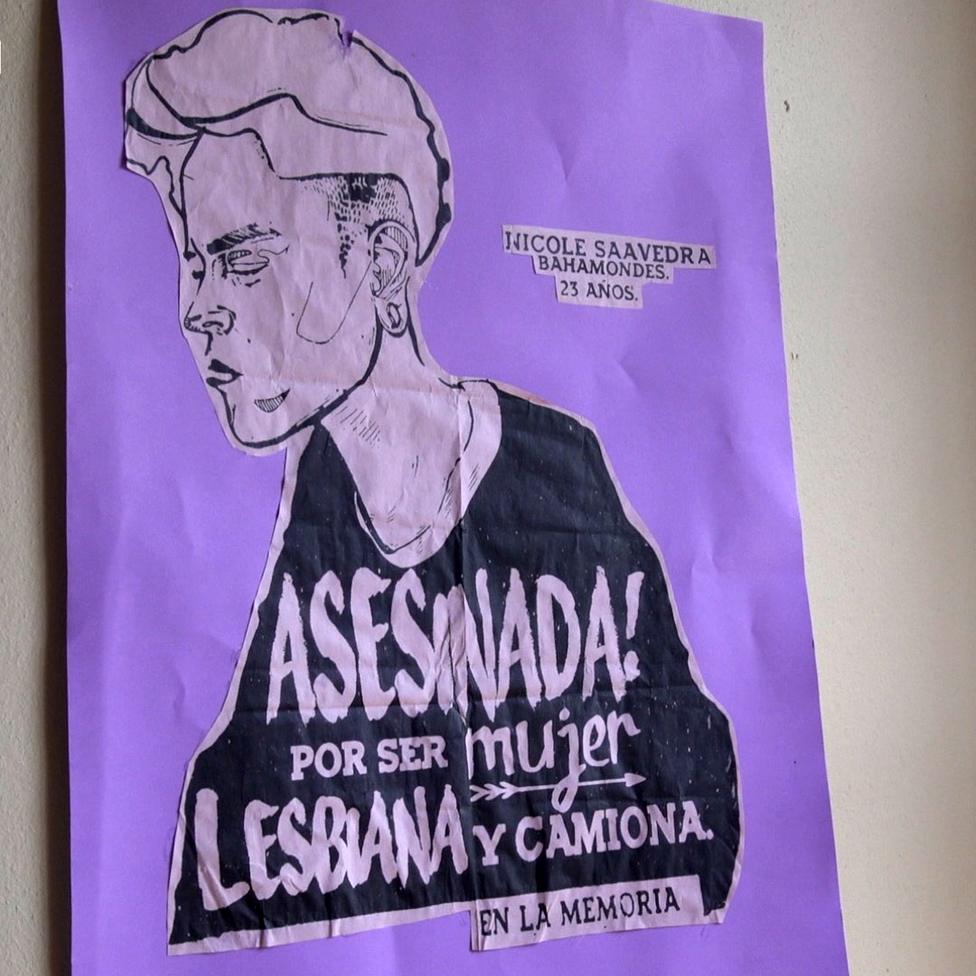

The dozens of distinctive, artfully cropped selfies on her Instagram page displayed it boldly. Her short, inky-dark hair, shaved close on the sides and a few inches long at the top, either flopped over her eyes or was pulled under a baseball cap. She mostly wore baggy jeans and hoodies. She wore plugs known as flesh tunnels" in large ear piercings, which elongated her earlobes and left large holes when she removed them.

She had a signature pose too - squinting into the lens broodingly, barely smiling. At first glance, Nicole's profile could have been that of a teenage skater boy.

That was intentional - she didn't want to look feminine.

The word "camiona" derives from the Spanish camionera - which means female lorry driver. It was once used as an insult towards butch lesbians in the Spanish-speaking world, but young lesbians have now reclaimed it. It's a distinct lesbian identity in Chile, says Karen Vergara, a lesbian activist in Quillota, the town where Nicole went missing. Camionas, she says, crop their hair short and wear "masculine" clothes - low-slung baggy jeans, checked shirts and baseball caps.

"Camionas do not want to identify with typically feminine styles imposed on women through a male gaze," says Karen.

"The clothing is a big part of that. It's a way to recognise each other in the street. In the lesbian community, camionas are our courageous sisters who, despite lesbophobia, dare to show their lesbianism."

It was this identity, Nicole's cousin believes, that sealed her fate.

"I think Nicole was murdered for being a lesbian, for her way of dressing," says María. "Because she dressed in a more masculine way."

Lesbians in Chile call the Fifth region - the region where Nicole lived - the Red Zone, because of its history of anti-lesbian violence.

"How to describe the Fifth region to people who have never been here?" Karen Vergara asks. "I would start by saying that we are on high alert here, because of lesbophobia."

Chile is made up of 16 administrative regions. The Fifth, about half way between the country's northern and southernmost tips, is these days officially called Valparaíso region after the port city that is its capital. But much of the region is rural, dominated by the booming avocado industry.

Feminist lawyer Silvana del Valle says the region has "an air about it" - including a machismo that leaves minorities feeling vulnerable, and some of the most active neo-Nazi gangs in the country. According to two people who attended the party in Quillota, the night before Nicole died, a neo-Nazi was also present for at least some of the time, and this made Nicole uncomfortable.

"Valparaíso is strange," agrees Sebastian Ayala, a film director making a documentary about the history of lesbian attacks in Chile. "When you talk to camionas and trans women in Chile, women who are outwardly more masculine-looking, they all know about Valparaíso and they try not to go there. They know about the attacks."

The most recent took place on 17 March, in a square in Valparaíso city, when a group of young men shouted lesbophobic expletives as they whipped a young camiona with chains, leaving her bloodied and badly shaken.

"Of course there's paranoia because of those attacks, but the feeling that the LGBT community were under attack, well that had been going on for decades," says Ayala. "Since Divine, probably."

You may also be interested in:

Divine nightclub, a converted townhouse in Valparaíso city, was the hangout for the Fifth region's LGBT community in the early 1990s. On 4 September 1993, the club opened after refurbishment to an excited group of about 60 people. There were new carpets on its floors and walls and fishermen's nets hanging from its roof - a cheeky nod to the port, and also to sailors, who had become a kitsch symbol of '90s gay culture.

Chile had just beaten Poland in the penalty shootout to take third place in the Fifa Under-17 World Championship and the mood was high as drag queens, lesbians and bi and gay men danced to pop music. But within hours 16 people had died in a fire so severe that only two could be identified without dental records. It had been caused by the wires of the lighting system overheating, police said, but many survivors and relatives of those who died suspected foul play.

It wasn't as if there was no motive. Divine, which was just a few years old, had not been a popular addition to the neighbourhood.

We feel under threat - as soon as you step out of your home you are in danger

The club and its staff had been receiving threats for months, and women complained of verbal abuse whenever they entered or left. A group of survivors formed a group called Acción Gay (Gay Action), demanding another investigation into the fire. They are still active today.

"It became a simmering paranoia with that generation," says Sebastian Ayala, "a question mark."

It's not clear whether Nicole knew about the fire at Divine, but she knew about the murder of María Pía Castro. Nicole had a few things in common with María. Both were young women from the Fifth region. They were from single-parent, working-class households. They were camionas.

The death of the 19-year-old footballer from the small town of Olmué sent shockwaves through Chile's lesbian community in 2008. She had faced abuse from local boys - she had been hit, yelled at, spat on - but hadn't stopped her from dressing the way she did, or telling her friends that she was a lesbian.

"But telling friends about your private life in a small community has consequences," says Karen Vergara. "It doesn't stay a private conversation."

On 13 February 2008, she was found dead, her body so badly burnt that she could only be identified through DNA tests. A post-mortem examination showed that she had also experienced a severe blow to the back of her head. Her body had been dumped on a hill, just miles away from where Nicole's would be found eight years later.

The case was closed in 2017, as no suspects had been identified.

María, then Nicole. No killer identified in either case. Feminist and lesbian groups could not fail to be deeply troubled.

Then, a year after Nicole's killing - on 7 March 2017 - the body of a third young camiona was found in the Fifth region. The news terrified women already on edge, confirming the region as a danger zone for young lesbians. But this murder was different.

Twenty-three-year-old Susana Sanhueza was found in a rubbish bag inside the town hall in San Felipe, where the animal rights group she worked for rented office space.

She had been dead a week.

WhatsApp messages read out in court reveal that she had been meeting a friend, fellow activist Cristian Muñoz, who later told police that he witnessed Susana having a seizure in the office and put her body in the rubbish bag, believing she was dead. He denies murder and his family say he has been admitted to a psychiatric ward while awaiting trail.

Susana Sanhueza

Susana's family believe that she was killed because Cristian was in love with her and was frustrated that he couldn't have a relationship with her. Some argue that Susana's death was not a result of homophobic prejudice, but Karen Vergara disagrees.

"We, the lesbian community in the region, still count Susana's death as lesbophobia," she says. "Whether it was a murder or Susana did suffer from a seizure, Cristian was pursuing a woman who had told him that she would always be unavailable to him. His lack of acceptance that she was a lesbian, and then not alerting the police, speaks to a hatred of gay women. That is misogyny and homophobia combined. It's lesbophobia."

Susana's death caused a number of WhatsApp groups to spring up in the Fifth region, for lesbians to warn each other of potential dangers, or of verbal and physical attacks. Admins of three groups told the BBC that there are at least three or four alerts a week.

"We call the Fifth region Chile's red zone for lesbians because of María, Nicole and Susana," says Karen Vergara. "There are many other attacks. Not as brutal or fatal as these but enough to land lesbians - especially camionas - in hospital. "We as lesbians are always on red alert in this town [Quillota]. Day and night, 24 hours a day 365 days a year. We feel under threat. As soon as you step out of your home you are in danger.

"When other lesbians come to see us from Santiago, they feel our fear. This region is like that."

But in February this year, a violent attack on a camiona in Santiago, Chile's capital, showed that lesbophobic bloodshed could occur there too.

In the early hours of Valentine's Day, 24-year-old Carolina Torres and her girlfriend, Estefania Opazo, were walking home with another friend from a lacklustre football match. Carolina's favourite football team, the University of Chile - also known as La U - had just drawn 0-0 with Melgar in the third phase of the Libertadores Cup. It had been a forgettable game.

The trio made their way down a busy street in the Santiago suburb of Pudahuel, close to where Carolina lived with her mother and father. Carolina and Estefania chose not to hold hands to avoid offending anyone.

Carolina Torres (right) and Estefania Opazo

Suddenly, Carolina felt a force to the back of her head. Then darkness. She had fallen unconscious, and would remain in a coma for a week.

She suffered a fractured skull, a broken nose, internal bleeding and permanent damage to her hearing. There were two male attackers. One had used a large wooden pole to hit her repeatedly on the back of her head, only stopping when Estefania threw herself on top of Carolina, using her body as a shield.

This is significant, says Carolina's mother, Mariela. Because unlike Carolina, who identifies as a camiona and dresses accordingly, Estefania is femme - a more feminine lesbian identity. The attackers targeted Carolina and not Estefania, says Mariela, because she represented an "unacceptable" face of womanhood. It was not just her sexual orientation that prompted violence, it was her appearance as a camiona.

"I want to make it very clear they were trying to kill her," she adds. "There is no other way of looking at it. The fact that she is here is a miracle."

Carolina knew one of her alleged attackers.

"Before this attack he threatened me. He said, 'I am going to kill you.' He said he was going to shoot me with a gun. He called me a lesbian and swore at me. He said, 'Why do you dress like a man?'"

Shortly after the BBC's interview with Carolina, two brothers, Miguel and Reinaldo Cortés Arancibia, were arrested and charged with attempted murder.

If people don't pay attention to this and do something about it - it's going to get worse

Lesbian activists tell the BBC that the arrest was unexpected, even though there was CCTV footage and the attackers were known to the victim. Generally, they say, lesbophobic violence goes unpunished. Carolina, who is taking more than 10 types of medication because of her injuries, says the attack has changed her forever. She suffers from nightmares and now feels unable to leave the home she shares with her parents.

"I liked to go out for walks. I like to do sports. And now I can't do anything," she says. "I have to be shut inside all day long here in my house. And I don't like it because I talk differently now." Her speech is slurred because of her injuries.

The attack on Carolina, on a busy road in Chile's capital, was the first reported in the capital since the 1984 murder of self-identified camiona, Mónica Briones. But just as in the Fifth region, feminist groups say other, less serious attacks on camionas take place without coming to the public's attention. Carolina's mother says her daughter's case represents the tip of an iceberg.

"If people don't pay attention to this and do something about it - it's going to get worse."

A drawing of Nicole Saavedra hangs on the wall of Lesbians Breaking the Silence. It's mounted on violet card, the universal colour of lesbian solidarity. Erika Montecinos looks at another poster she has up on her wall. It's of happier times, the first lesbian march at Santiago's Gay Pride, in 2001.

Santiago does have an openly gay scene. It's most noticeable in the Bellavista neighbourhood, where the nightclubs and bars have rainbow flags on the windows and same-sex couples walk holding hands. Nicole Saavedra's friends say she enjoyed nights out the area, when visiting the capital. But outside this one neighbourhood the mood is very different, Erika says.

She runs her organisation in a secret location behind barred windows. A large tree in the garden ensures that passers-by won't see the rainbow flag inside.

The irony of an organisation with such a defiant name having to hide itself from the public is not lost on Erika. But other LGBT organisations have been subjected to intimidation and threats from hate groups, she says.

While the Fifth region is a hotbed of lesbophobic violence, she says, the problem exists throughout the country. In a survey of 850 lesbian and bisexual women carried out by Lesbians Breaking the Silence last year, 75% said they had suffered street harassment. After the attack on Carolina Torres, Erika's organisation set up a WhatsApp number called the Linea Violeta (the Violet Line), which received more than 100 reports of violence or intimidation in a month. None were reported to police, she says, because the callers saw no point - they were convinced no action would be taken.

To make prosecution in cases of femicide more likely, Chile's femicide law ensures that specialist investigating lawyers are assigned to victims' families, to help gather the necessary evidence. But the murder of a lesbian does not count as femicide.

"Femicide is the sex-based murder of a woman committed by a man," says Silvana del Valle, a law professor at the University Academy of Christian Humanism in Santiago. "But to qualify as an act of femicide, the killer should have been in a current or former spousal or cohabitant relationship with the victim.

"Lesbian women will of course not be in a romantic relationship with a man, even if the murder is sex-based, even if the motivation is because she is a certain 'type' of woman, a lesbian."

Del Valle argues that prosecutors and the police are under little pressure to solve these murders because there is no national outcry and in most cases - including Nicole's, María's and Susana's - these women are from poorer backgrounds.

It troubles Nicole Saavedra's family that her killer, or killers, remain uncaught.

There's a silence surrounding the murder in the community, says her cousin, María Bahamondes; Nicole's friends seem to be scared of something and no longer speak to the family.

And then there's the police.

"I feel that they have treated us badly," María says. "I often felt like they were laughing at us. They would have meetings with us but they wouldn't even know Nicole's name. They would give us the same files that they had given us months before. We would go there and they would cancel the meeting with us. They didn't do anything."

In a statement to the BBC, the public prosecutor's office in the Fifth region rejected the accusation that police were inactive in the face of lesbophobic violence, or could be held to blame for it.

"All parts of society have failed when a crime is committed. Blaming only one factor, like the Public Prosecutor of the Fifth Region, undermines the problem, simplifies it and ultimately prevents a solution," the statement said. "Only when every person understands the role they play in society's lack of acceptance of people with different sexual orientations, will we approach a solution to these crimes."

María Bahamondes, demanding justice for her cousin

In the statement, the public prosecutor also insisted that police were committed to investigating Nicole's murder and said the Chilean Public Prosecutor's office was setting up a team to study the problem of violence against LGBT people.

"I wasn't aware that lesbians call it a 'red zone' but now that you mention it, that fits with the latest events in Valparaíso," said Daniel Morales, the mayor of Limache, where the bodies of María Pía Castro and Nicole were found. He added that his office was working with the police to install more CCTV cameras and was using surveillance drones to protect the public.

But that's little consolation for María as she contemplates the unsolved murder of her cousin.

"I can't deal with it any more," she says, shaking slightly. "This story has to come to its end. And we need to find out who did this. Otherwise there is no justice. If we don't find the people who are guilty of this, there is no justice for Nicole."

María Bahamondes, Karen Vergara and three other women were arrested on Saturday and held overnight for occupying the office of the public prosecutor in Quillota and locking themselves inside, after a demonstration marking the three-year anniversary of Nicole Saavedra's death.

The women were demanding a meeting with the prosecutor in charge of the investigation, whom they accused of failing to make serious efforts to solve the case. Local media quoted the chief prosecutor of Quillota as saying the investigation into Nicole's death was "proceeding normally".

They were released following pressure from the Chilean Human Rights Institute.

Follow Megha Mohan on Twitter @meghamohan, external

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.