'My flat was covered in mould - I rented it from the deputy mayor'

- Published

The collapse of two apartment buildings in Marseille last November left the city in mourning for eight people who died, but also furious. In the past, the story of a young woman whose rented flat grew a layer of black mould might have received little attention - now it's seen as cutting to the heart of the city's problems.

Half-way up the Rue d'Aubagne there's a gap where numbers 63, 65 and 67 used to stand - this is where two apartment buildings crumbled in a matter of seconds at 09:00 on 5 November 2018. Among the eight victims pulled from the rubble were a mother from the Comoros islands who had just returned from taking her son to school, an Italian student and a young man from Algeria, who'd recently crossed the Mediterranean in a small boat, dreaming of a new life in France.

That tells you something about the kind of place it is. Someone counted more than 100 different nationalities living and working here. Shoppers weave past piles of uncollected rubbish, graffiti-covered doors and young men hawking contraband cigarettes. Restaurants sell Moroccan couscous, Algerian cakes, Neapolitan pizzas, French cheese, Indian curries and Ivorian stews.

Many houses close to the collapsed houses were evacuated

The tall townhouses were built in the 18th Century by wealthy merchants. But over the years they've been subdivided into smaller and smaller flats. Some buildings have flooded cellars and water-saturated walls - and it was no secret that many had become unhealthy and unsafe.

A 2014 map of Noailles, the neighbourhood surrounding the Rue D'Aubagne, uses different colours to show the state of each building: green for good; yellow for a little shabby; orange for substandard and unhealthy (usually because of damp, infestations and rot); and red for high-risk, indicating there is a danger the structure could collapse. It was made by an urban development body attached to the city hall.

The buildings coloured red were classified as "high risk" five years ago

A government report published in 2015 said 100,000 Marseille residents were living in squalid, private accommodation dangerous to their health or security. But despite these warnings little was done. The slum landlords, known as marchands de sommeil - sellers of sleep, were allowed to continue as before, making money from poorly maintained and hazardous properties.

The problem is not confined to Noailles, however, as 23-year-old Jennifer Mbon's story illustrates.

"I was in a relationship which broke up and I suddenly found myself homeless," says Jennifer, who works as an administrative assistant in a care home for the elderly, earning France's minimum wage.

She saw an advert for a studio, available for 520 euros (£466) a month in the upmarket Eighth district of Marseilles, and went to have a look.

It was described as a "small detached house", though it was poky, little more than a shed, and the rent was high for someone earning only 800 euros a month. But it seemed quite nice and had been freshly painted, so she took it.

The good impression created by the new paint soon began to wear off, however.

"Within a few months I noticed mould growing up the wall behind my sofa-bed," Jennifer says. "It spread very quickly to my wardrobe, to the kitchen, the bathroom and even the floor."

Mould grows round a socket in Jennifer Mbon's apartment

The mould wasn't just unpleasant to look at, it had a foul smell, and it got everywhere. Jennifer shows me some pictures of her clothes and shoes which she had to throw away as they were covered in fuzzy green slime.

And there was another problem. The electricity meter was positioned dangerously - and illegally - right opposite the shower.

Shower on the right, electricity meter on the left (behind the half-open white cupboard door)

Jennifer's lawyer, Julie Savi, tells me that when her client signed the lease the property was a garage for motorbikes. It was never meant for human habitation. But for some reason the mayor of Marseille himself signed a document re-designating it as a studio apartment.

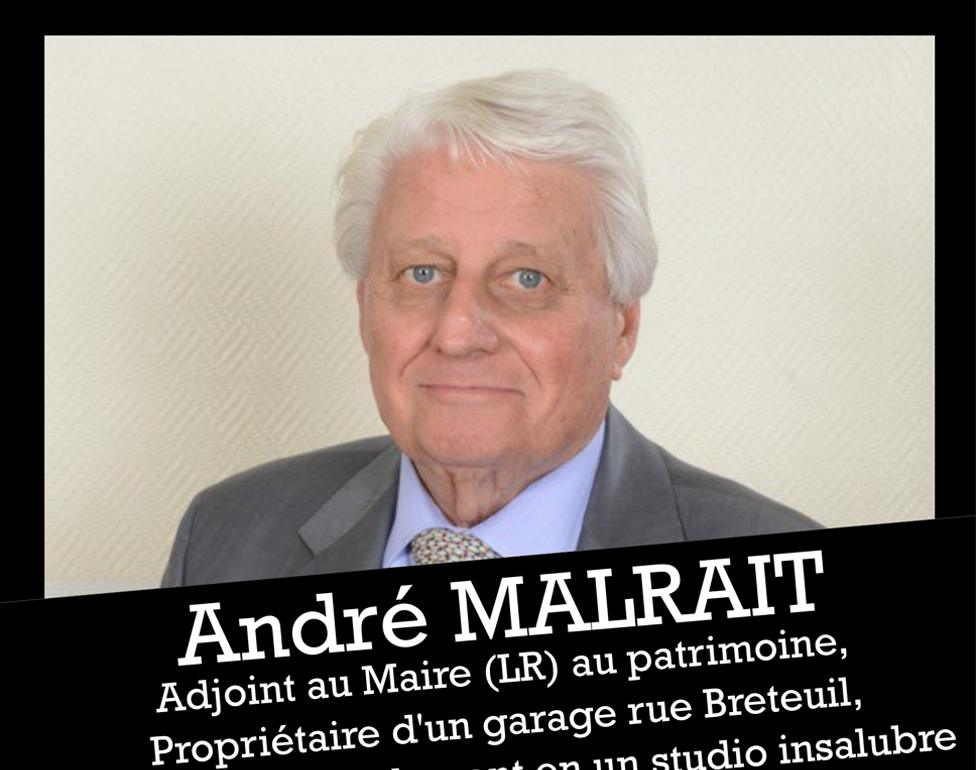

The owner of the flat turned out to be Marseille's deputy mayor in charge of heritage and historic monuments, André Malrait - an architect and prominent member of the ruling party in the city, the centre-right Les Republicains.

Jennifer only discovered this when he contacted her employers. "He demanded that my company pay him the rent I owed out of my salary directly, without going through a court bailiff," she says.

"I thought, 'He has got a real nerve first of all to rent me such a hovel and secondly to allow himself to ring my boss and play that kind of power game,'" she adds. "He knew that my company had been subcontracted by the city of Marseille and that my employer would find it hard, in those circumstances, to stand up for me."

Poster calling for Andre Malrait to be sacked

When I ring André Malrait, he tells me the studio flat was ruined by Jennifer, who should have left the windows open. He says he has since moved the electricity meter out of the bathroom. Then he hangs up.

Although city inspectors described the studio as insalubre - harmful to health - in court the judge took a more lenient view. Jennifer got a paltry 800 euros compensation for "certain defects". Her lawyer will appeal.

Find out more

Listen on BBC Sounds to Marseille: France's crumbling city, Lucy Ash's documentary for Assignment on the BBC World Service

"In French law there is a provision to jail people for the offence of putting people at risk with a structure which might collapse, or electricity which is not installed according to the regulations," says Julie Savi. "I am not saying Jennifer had all those problems in her studio. Yet the place was harmful to her health, there were some risks and the case is aggravated by the fact that her landlord is a qualified architect and could not have been ignorant of the rules or the fact that he was renting substandard accommodation."

According to residents, the deputy mayor is not the only politician who doubles as a slum landlord.

Soon after the buildings collapsed on the Rue d'Aubagne, mock election posters with mugshots of four local politicians appeared. Vote for this shady character, said the text beneath, he'll rent you a dump.

Posters calling sarcastically on people to vote for the four landlord politicians

André Malrait was one of the four. Another was Xavier Cachard, the fleshy, bespectacled vice-president of the regional council, who actually owned one of the 10 flats in 65 Rue d'Aubagne which collapsed. He denies his property was in a bad condition and says he couldn't have done anything to prevent the tragedy.

"The spotlight is on me because of my job," he complained to a local radio station. "It's a private matter but some people want to politicise it."

There have been calls for the four men to resign. Cachard, in fact, tendered his resignation but it was refused, pending the outcome of a judicial inquiry to determine responsibility for the disaster. As for Malrait, he told the La Provence newspaper that he considered himself "irreproachable" and that he was amazed by the amount of coverage the affair was getting in the media.

The tragedy in the Rue d'Aubagne focused attention in France on substandard housing like never before. In response, the French Senate this month passed at first reading a bill to crack down on slum landlords, and create a special housing police.

In the days and weeks following the accident, 311 buildings were evacuated across the city and 2,558 people were forced to leave their homes. Some have since been told it is safe to return but they live with a sense of dread according to Zania Serra, a local artist and fashion designer.

"When it happened, I heard a loud boom, saw the smoke and I thought it was a terrorist attack," she says. "I didn't have a clue it was houses falling down. Now people around here feel anxious, they can't sleep at night, worrying if they are safe or not."

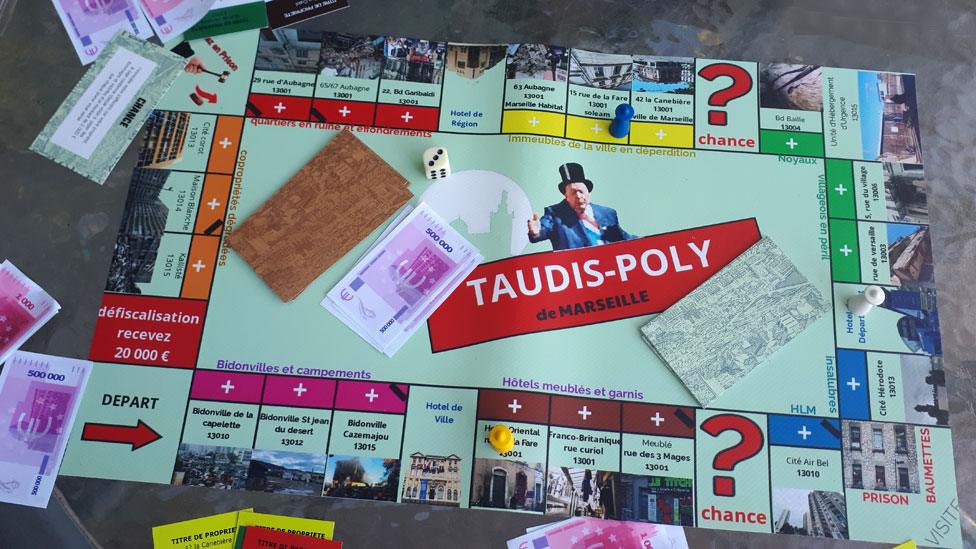

Activists have invented a Marseille version of Monopoly to draw attention to the crisis.

They call it Taudis-poly - Slum-opoly. "Housing is a right - Hovels a crime!" says the writing on the red-and-white box. With its familiar dice, paper money and plastic property, the board game is designed to expose a corrupt housing system which gives endless tax breaks to owners who buy properties and fail to maintain them.

The game was the brainchild of Fathi Bouaroua, who has spent much of his life working with social housing and supporting the homeless. He was inspired by a banner carried by a woman in a December demonstration, a month after the tragedy, which read: "Stop playing Monopoly with our lives!"

"We all came together after the accident," says Zania Serra. "No matter where people are from originally, we are all proud to live in Noailles and we will fight to stay here." She shows me a shopping bag with a heart and a fist on it which she designed and is selling to raise money for the eight victims' families and people who need to be rehoused.

A volunteer working with those made homeless displays one of Zania Serra's bags

Keny Arkana, a prominent Marseille rapper, also did her bit for the beleaguered community.

Her song, We Are All Children of Marseille, external, became an anthem and a call to arms during the street protests after the buildings collapsed. "Our city is in mourning," go the lyrics. "We are in tears. How many warnings did our town hall ignore?"

The spirit of Noailles is one of the things that Philipe Pujol, Marseille's best-known journalist, admires about it.

"Marseille is the last city in France with poor people living in the centre. Usually they have been pushed out to the suburbs," he says. "It hasn't been completely franchised or gentrified - and it still has a soul."

You may also be interested in:

Theo had just turned 17 when he became homeless. He turned to the council for help - but was given only a one-man tent.