'My parents told everyone I was dead'

- Published

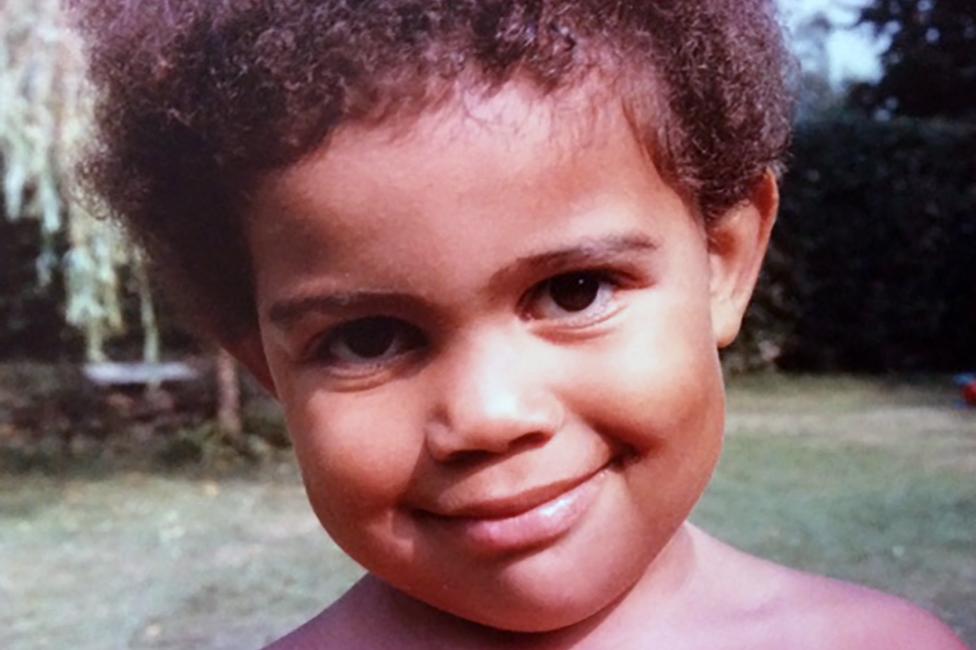

In 1980 a baby girl was given up for adoption for being the wrong colour - she was mixed-race, her parents were white, and this was apartheid South Africa. But being brought up by a white couple in the UK left her searching for her place in the world. She only found it when she returned to the country of her birth.

As the plane touched down in Johannesburg, Sara-Jayne King caught her breath. More than 25 years had passed since she had last seen South Africa.

She had no conscious memories of it. She had left Johannesburg as a seven-week-old infant, to be deposited by her biological mother in England. The years in between had not been easy. Sara-Jayne had never come to terms with being abandoned by her birth mother, and had struggled as a biracial child in middle-class Surrey.

She got off the plane, walking through the airport and towards the car that would take her to the rehab centre. Here, Sara-Jayne hoped to rid herself of her self-harming behaviour and sort out the pieces of her life. As the car swept her along, a familiarity washed over her. "I've been here before," she thought. "I've been here before, and I belong."

Growing up in the home counties, Sara-Jayne knew she looked different from her parents, but never thought of "black" as her identity until others in the town pointed it out. Her classmates often touched her hair, telling her it felt like wire wool. For a long time, Sara-Jayne was the only black girl she knew. Others told her she was different, so she felt different. "We sort of absorb other people's views of us," she says.

Bit by bit, Sara-Jayne came to feel there was something wrong with being black.

Grappling with her race and adoption became a constant, uncomfortable reminder that she lacked a clear picture of who she was. What it meant to be black, or South African or adopted - it was all muddled in Sara-Jayne's mind. She felt alienated and alone.

The details of her adoption were vague. She was told her adoptive mother had been unable to have a baby, and that she herself had come from South Africa. That was all.

She had one older brother who was also adopted and black. Her only other reference to black people was 1980s British television, which she said was neither realistic nor flattering to people of colour. Other than that, she had no racial mirrors.

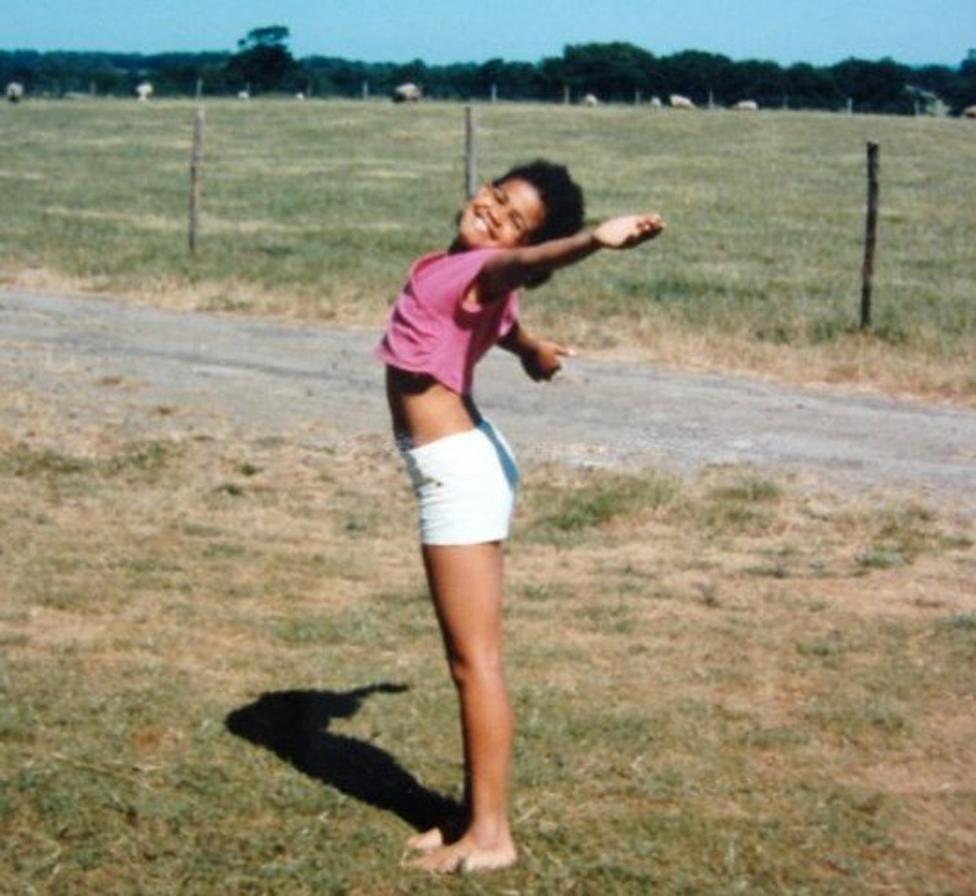

"I woke up every morning and looked out across fields and saw chickens and lambs," she says. "I really was living a very sort of white, middle-class existence."

In her village, Crowhurst, Africans were viewed as destitute. Her school held food collections for starving children in Ethiopia. Sara-Jayne remembers seeing children covered in flies in dusty landscapes and assumed those images defined her, as well. "It was a place to be pitied and it was a place to sort of turn one's nose up at," she says. "It was a place to be grateful that I had been rescued from."

While Sara-Jayne believed being black was bad, she soon learned blackness and brownness came in varying degrees. While her blackness was undesirable, others' could be attractive.

When she was eight years old, three girls from Mauritius moved to town. They were beautiful, with soft wavy hair and glowing skin. They were the right type of brown people. Meanwhile, Sara-Jayne's hair proved unruly. Every Sunday morning her father struggled to brush it as Sara-Jayne squirmed in pain. It was something she felt guilty about until she had it relaxed for the first time as a teenager.

Despite their best intentions, her family exacerbated her feeling of isolation. Sara-Jayne remembers once watching the summer Olympics with her grandmother. As the competition began, she turned to Sara-Jayne, informing her that she would cheer for Britain and her granddaughter could root "for Africa".

At the age of 14, Sara-Jayne made an unexpected discovery. While snooping around her mother's room, she uncovered a letter from her biological mother, written nearly a year after her birth. The letter was addressed to her. She opened it and began reading. The story of her adoption, in shocking detail, unfolded before her.

Find out more

Listen to Sara-Jayne King on Outlook on the BBC World Service

She learned that her biological mother, a white British woman in a relationship with a white man, had had an affair with a black man. When she became pregnant, she had been unsure which man was the father. The child appeared white at birth, and her mother named the baby Karoline. But a few weeks later her mother realised the child was not, in fact, white. Karoline was the black man's child, and her existence became not a source of parental joy, but a problem to be dealt with.

At the time of Karoline's birth, the South African Immorality Act forbade interracial sexual relationships, and Karoline was proof of an illegal affair. So her biological mother and her husband, along with their doctor, devised a plan. They claimed Karoline suffered from a rare kidney disease and required advanced medical treatment in London. But once there they gave her up for adoption. Returning to South Africa empty-handed, the couple told everyone at home that Karoline had died.

Sara-Jayne struggled with the knowledge that her mother had given her up, and had even pretended she was dead. "The colour of my skin was so abhorrent, and what my biological parents had done was so disgusting, that I would have to be taken from my homeland and raised elsewhere," she says. "I felt this feeling of how dreadful must one be as a person that the one person on Earth who is supposed to love you, and care for you, and nurture you no matter what, was able to do what my biological mother had done, which was to give away her child."

This bitter feeling of rejection had begun to manifest itself even before Sara-Jayne read the letter. She had deliberately overdosed on Paracetamol at the age of 13. Later, she began cutting herself.

A few years after reading the letter, in her first year studying law at the University of Greenwich, she contacted her biological mother through the adoption agency. She responded, saying she would answer Sara-Jayne's questions, but then had no desire for continued communication. She never expressed remorse or offered an apology.

At around this time, Sara-Jayne developed an eating disorder and started self-medicating with alcohol and codeine. Despite this, she completed her degree and earned a master's degree in journalism from the University of Canterbury. She landed a string of good jobs, moving from England to Dubai and began building a successful radio career.

But her past hung over her like a cloud she could not escape. Her adoptive father was no longer in her life, her brother had killed himself and her biological mother had rejected her a second time. Continuing to struggle with eating disorders, alcohol and self-harm she was fired from her job in Dubai. Eventually, she reached a breaking point. It was 2007 and time for Sara-Jayne to get help, and she discovered rehab was cheaper in South Africa. Leaving Johannesburg had set Sara-Jayne on her path towards emotional turmoil and substance abuse. She hoped returning would heal those wounds.

On the final descent into Johannesburg, Sara-Jayne looked out over the country that could have been her home. "We're still in the air and I thought, 'Something momentous is happening,'" she says. "The plane wheels touched down and I thought, 'I'm home.'"

As the car drove her to the rehab centre, she felt she had been on the same roads before - and as it turns out, she had. The hospital where her mother gave birth is only three streets away. Sara-Jayne thinks a sense of the place must have been engraved on her mind, at only a few weeks old. She felt instinctively that she belonged.

Sara-Jayne spent about a year in treatment in South Africa, moving between Johannesburg and Cape Town. While there, she met her half-brother - her biological mother's other child - and for a while they were quite close. She returned to the UK, but, after several years of shuttling back and forth between London and Cape Town, she decided to move to South Africa. "It felt like home," she says.

As she stood in her room packing her bags the night before her move in 2013, her friend messaged her with the news that Nelson Mandela had died. "The South Africa that I came back to, to call my permanent home, was a South Africa in mourning, but also in celebration," she says. "It was South Africa at its best - and we don't see that very often."

When Sara-Jayne touched down in South Africa, she knew this time it was for good. She was ready to realise her identity as a black South African woman.

One step she needed to take was to formally change her name. "Karoline" had been a back-up name, an alternate version of Sara-Jayne had she been born white, but "Karoline King" was the name on her South African birth certificate. To fully become herself, Sara-Jayne needed to put Karoline to bed.

Even in the UK, her name had technically been Sarah Jane; her adoptive parents had named her Sarah, with Jane as her middle name. In order to stand out from the other Sarahs at school, she dropped the H, added a Y to Jane and hyphenated them.

This had been a small way for her to assert her own identity growing up, rather than the one forced upon her. Making it official was the next step. "I'll never forget the day that I finally went in and I collected my ID book," she says. "My name was Sara-Jayne King. And I thought, that's it. That fits. That's me."

Two years ago, Sara-Jayne released a book chronicling the circumstances of her adoption and the trajectory of her life afterwards. She had hired a private investigator to help her find her biological father, but without success. Then, while promoting her book on the radio, she mentioned his name. That's when Twitter jumped into action. Within 36 hours of the radio show airing, she had her father's phone number. She dialled it, and, for the first time, heard his voice on the phone. They talked for 30 minutes.

The pair spoke every day for a week before Sara-Jayne got on a plane to Johannesburg to meet her father, in person. They arranged to meet at a coffee shop in a shopping mall.

It was, she says, the best day of her life. "I will never forget him just walking around the corner, and we both just burst into tears, and he hugged me and he said, 'My daughter, my daughter,'" she says. "It suddenly dawned on me, I am someone's daughter. I am someone's daughter, and I belong."

Two years later. Sara-Jayne is considering one more name change - adding her father's last name to her own and becoming Makwala King. Though she lives in Cape Town, working for Cape Talk radio, she travels occasionally to Johannesburg to see her father and her three half-siblings. She still has a close relationship with her adoptive mother in the UK, but rejoices at having found her South African family.

And she now feels confident in her identity as a black South African. She never really felt British. When others attempt to put her in a box, it no longer throws her off balance like it used to. "I think some people still find that a difficult concept that actually, you don't get to decide who I am and how I identify," she says. "I couldn't give two hoots how other people think I should identify."

All pictures courtesy of Sara-Jayne King, who is the author of Killing Karoline

You may also be interested in...

Kati Pohler was abandoned in a market in China when she was three days old. Her parents left a note saying they would meet her on a famous bridge 10 or 20 years later. When the time arrived, Kati was living in America and had no idea. This is how she finally met her biological family.